Iron is one of the few nutrients where the margin between too little and too much is narrow enough to matter for your brain. Get too little, and your neurons cannot produce the dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine they need to support memory, attention, and learning. Get too much, and iron begins generating free radicals that damage the very cells it was supposed to fuel, accelerating the kind of neurodegeneration seen in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. The brain is caught in a biological balancing act, and the consequences of tipping in either direction are real and measurable.

Consider the scale of the problem on just one side of that equation. Nearly 2 billion people worldwide were affected by anemia in 2021, and dietary iron deficiency accounted for 66.2 percent of all cases, striking 825 million women and 444 million men, according to research published in The Lancet Haematology. On the other side, a 2025 RSNA study found that higher iron levels in specific brain regions predicted the onset of mild cognitive impairment in older adults who were otherwise cognitively normal. This article breaks down what iron actually does in the brain, how deficiency and overload each cause damage, who is most at risk during different life stages, and what practical steps you can take to protect your cognitive health.

Table of Contents

- Why Does the Brain Need Iron, and What Happens When It Runs Low?

- How Excess Iron Damages the Brain Through Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis

- Iron’s Role in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease

- How Much Iron Do You Actually Need, and How Do You Get the Right Amount?

- Iron and the Menopausal Brain: A Newly Recognized Risk

- Can Iron Supplementation Reverse Cognitive Damage?

- Iron Chelators and the Future of Brain Iron Research

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Why Does the Brain Need Iron, and What Happens When It Runs Low?

Iron is not just about red blood cells. In the brain, iron is required for neurotransmitter synthesis, including dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. It is essential for myelination, the process that insulates nerve fibers so electrical signals travel efficiently. It supports neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and mitochondrial respiration, the energy engine inside every neuron. Without adequate iron, these processes slow down or stall altogether. Research published in Annals of Medicine in 2025 confirmed the breadth of iron’s involvement across nearly every major function in the developing and aging brain. When iron levels drop, the effects show up in cognition before they show up on a blood test. Iron deficiency disrupts brain myelination, dopamine metabolism, and hippocampal function, leading to impaired attention, intelligence, memory, and sensory perception, according to a review in PMC.

In children, the damage can be especially severe: developmental delays, reduced school performance, and behavioral disorders are well-documented consequences. In newborns, cognitive damage from iron deficiency can become irreversible even after long-term supplementation, meaning the window for prevention is disturbingly short. A study presented at the American Society of Hematology found that iron deficiency anemia in otherwise healthy women causes measurable grey matter volume loss in the right temporal lobe and white matter decreases in the corpus callosum and cerebellum. This is not subtle biochemistry. It is visible brain shrinkage. What makes iron deficiency particularly dangerous for older adults is that the cognitive harm does not require full-blown anemia. Research published in ScienceDirect found that elderly patients show cognitive impairment from iron deficiency independent of anemia. The deficiency alone is sufficient to cause harm, which means standard blood tests that only check hemoglobin levels may miss the problem entirely.

How Excess Iron Damages the Brain Through Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis

If too little iron starves the brain, too much poisons it. Excess brain iron generates reactive oxygen species, commonly known as free radicals, which cause oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and a specific form of cell death called ferroptosis. This is not a theoretical risk. Research published in Nature’s Molecular Psychiatry laid out the mechanisms in detail: iron-driven oxidative damage attacks lipid membranes, disrupts energy production, and triggers cascading cellular destruction. The brain is particularly vulnerable to this kind of damage because it is enriched in polyunsaturated fatty acids and iron, a combination that makes neural tissue uniquely susceptible to ferroptosis, according to research in Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. Think of it this way: polyunsaturated fats are the kindling, and excess iron is the spark. Once oxidative damage begins, it tends to feed on itself.

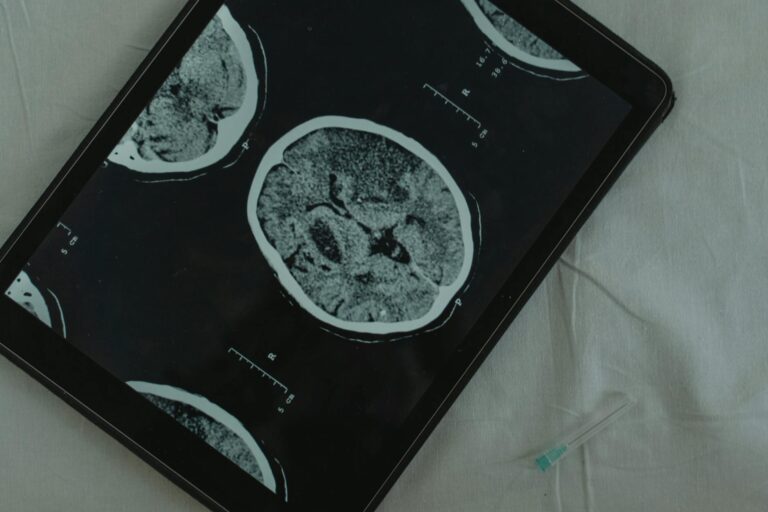

However, it is important to note that the iron accumulation seen in neurodegeneration is not necessarily caused by eating too much dietary iron. Brain iron regulation involves specialized transport proteins and barriers, and dysregulation of these systems, rather than simply high iron intake, is often the underlying problem. This is a critical distinction: the iron overload in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease reflects a failure of the brain’s iron management, not just a surplus in the bloodstream. That said, the connection between brain iron levels and disease progression is increasingly well-established. A 2025 RSNA study followed 158 participants for up to 7.5 years using quantitative susceptibility mapping on MRI. Researchers found that higher iron levels in the entorhinal cortex and putamen predicted the onset of mild cognitive impairment in cognitively normal older adults. Brain iron measurement may eventually become a routine part of dementia screening.

Iron’s Role in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease

In Alzheimer’s disease, iron does not just show up at the scene of the crime. It actively makes things worse. Research published in ScienceDirect found that iron accumulation promotes amyloid-beta aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation, two of the hallmark pathologies of Alzheimer’s. This creates a vicious cycle: the disease disrupts normal iron handling in the brain, which leads to more iron deposition, which accelerates amyloid and tau pathology, which further disrupts iron handling. Breaking this loop has become a major focus of therapeutic research. Parkinson’s disease tells a geographically specific story within the brain.

Iron accumulates in the substantia nigra, the region responsible for dopamine production, increasing oxidative stress and protein aggregation. A review published in the Journal of Neurochemistry detailed how this targeted iron buildup contributes to the death of dopaminergic neurons, the defining feature of Parkinson’s. For families watching a loved one develop tremors, rigidity, or slowed movement, the underlying biochemistry involves iron doing damage in one particular neighborhood of the brain. What makes both diseases so difficult to address is that iron’s role is tangled up with many other factors. Genetics, inflammation, vascular health, and aging itself all influence how iron accumulates and what damage it causes. Reducing brain iron is not as simple as reducing dietary iron, which is why drug development has focused on iron chelators, compounds that can cross the blood-brain barrier and bind excess iron directly at the site of damage.

How Much Iron Do You Actually Need, and How Do You Get the Right Amount?

The National Institutes of Health provides clear guidelines. Men and postmenopausal women need 8 milligrams of iron per day. Premenopausal women aged 19 to 50 need 18 milligrams per day, more than double the amount, primarily because of menstrual blood loss. The tolerable upper intake level is 45 milligrams per day, based on the threshold for gastrointestinal distress. These numbers leave meaningful room between the minimum and the ceiling, but there are important caveats. Vegetarians need nearly twice the recommended daily allowance because nonheme iron from plants is less bioavailable than heme iron from animal sources, according to the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements.

A vegetarian woman of reproductive age might need upwards of 32 milligrams of iron per day from food, which is genuinely difficult to achieve without careful planning or supplementation. Pairing iron-rich plant foods with vitamin C improves absorption, while calcium, tannins in tea and coffee, and phytates in whole grains can inhibit it. For someone eating a standard Western diet heavy in red meat, iron overload from food alone is uncommon but not impossible, particularly for men and postmenopausal women who lack a regular mechanism for iron loss. The tradeoff is real: the same dietary habits that protect against deficiency in one population can push another toward excess. The WHO reports that 40 percent of children aged 6 to 59 months, 37 percent of pregnant women, and 30 percent of women aged 15 to 49 are affected by anemia globally. The burden falls hardest on Western sub-Saharan Africa, with a 47.4 percent prevalence, and South Asia at 35.7 percent, while Australasia and Western Europe sit at 5.7 percent and 6 percent respectively. Geography, income, and diet all shape where the risk lies.

Iron and the Menopausal Brain: A Newly Recognized Risk

Menopause has long been associated with cognitive complaints, often dismissed as brain fog and attributed loosely to hormonal changes. A 2025 University of Oklahoma study published in Nutrients added a new dimension to this conversation. Researchers found that perimenopausal women with below-expected blood iron levels performed worse on measures of memory, attention, and cognition, even though none of the women were clinically iron-deficient by standard laboratory criteria. This is a critical finding because it suggests that the conventional cutoffs for iron deficiency may be too low when it comes to brain health. The natural concern is that supplementing iron to support cognition during perimenopause could contribute to dangerous brain iron accumulation later in life.

The Oklahoma study addressed this directly: sufficient blood iron did not lead to unsafe brain iron levels. Adequate dietary iron supports cognition without raising neurodegeneration risk. However, this does not mean that all women approaching menopause should start taking iron pills without guidance. Iron supplementation in someone who does not need it can cause gastrointestinal problems, and in individuals with undiagnosed hemochromatosis, a genetic condition causing iron overload, supplementation can be genuinely dangerous. A ferritin blood test is the minimum necessary step before making any changes.

Can Iron Supplementation Reverse Cognitive Damage?

The evidence here is encouraging but limited. A 2026 review in Frontiers in Nutrition found that iron supplementation showed modest benefits in intelligence, memory, and attention among anemic children. That word modest is important. Supplementation can help, but it does not reliably restore full cognitive function, especially in cases where deficiency occurred during critical developmental periods.

In non-deficient populations, the effects of supplementation were negligible, reinforcing the principle that iron helps those who need it and does little for those who do not. For older adults with iron deficiency and cognitive symptoms, supplementation may improve function, but the evidence base is thinner than for children. The elderly are also more likely to have comorbidities that complicate iron metabolism, including chronic kidney disease, inflammatory conditions, and medication interactions that affect absorption. Supplementation in this population should be monitored with regular blood work, not managed by guesswork.

Iron Chelators and the Future of Brain Iron Research

The most promising frontier in this field involves targeting excess brain iron directly. Iron-chelating compounds such as deferiprone, clioquinol, and PBT2 are being developed as potential treatments for neurodegenerative diseases driven by brain iron overload. These drugs cross the blood-brain barrier and bind excess iron, removing it from the cycle of oxidative damage.

Clinical trials are ongoing, and while no iron chelator has yet been approved specifically for Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, early results have been enough to sustain serious research investment. An even more novel approach involves ferroptosis inhibitors delivered intranasally, which have shown promise in animal models for reversing iron-accumulation-related cognitive impairment, according to research published in Science. Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood-brain barrier entirely, offering a more direct route to affected tissue. These therapies are still years from clinical availability, but they represent a fundamental shift in how we think about treating neurodegeneration: not just clearing plaques or replacing neurotransmitters, but addressing the underlying iron dysregulation that may drive disease progression from the beginning.

Conclusion

Iron occupies a unique position among nutrients that affect the brain. Too little disrupts the fundamental chemistry of thought, memory, and mood. Too much triggers a cascade of oxidative destruction that is increasingly linked to Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and age-related cognitive decline. The brain needs iron the way an engine needs oil: essential for operation, destructive in excess, and damaging when absent. The research is clear that maintaining iron levels within the recommended range is one of the most concrete, actionable steps available for protecting long-term cognitive health.

For caregivers and individuals concerned about brain health, the practical takeaway is straightforward. Ask your doctor to check ferritin levels, not just hemoglobin. Understand your dietary iron sources and whether your intake matches your age, sex, and dietary pattern. Do not supplement iron without knowing your current status. And stay aware of the emerging science around brain iron and neurodegeneration, because the tools to measure and manage brain iron are advancing rapidly, and what we know today will look incomplete in five years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can eating too much red meat cause dangerous iron buildup in the brain?

For most people, dietary iron from food alone does not directly cause brain iron overload. Brain iron accumulation in neurodegenerative disease reflects failures in the brain’s own iron regulation systems, not simply high dietary intake. However, men and postmenopausal women who consume large amounts of red meat and take iron supplements may develop elevated body iron stores, which is worth monitoring with a doctor.

Should I stop taking iron supplements if I am worried about Alzheimer’s?

Not without checking your iron levels first. If you are iron-deficient, supplementation protects your brain. The 2025 University of Oklahoma study found that adequate blood iron did not lead to unsafe brain iron levels. The risk comes from dysregulated iron in the brain, not from appropriate supplementation. Talk to your doctor about testing your ferritin levels before making any changes.

Is iron deficiency really common enough to worry about?

Yes. Nearly 2 billion people were affected by anemia in 2021, with dietary iron deficiency accounting for 66.2 percent of cases. Women of reproductive age, young children, and vegetarians are at highest risk. Even in Western Europe and Australasia, where prevalence is lowest, 5 to 6 percent of the population is affected.

Can iron deficiency cause permanent brain damage?

In some cases, yes. Research shows that in newborns, cognitive damage from iron deficiency can become irreversible even after long-term supplementation. In adults, the evidence is more mixed, with supplementation showing modest cognitive improvements in deficient individuals. Early detection and treatment are critical, especially in infants and young children.

What blood test should I ask for to check my iron status?

Ask for a serum ferritin test, which measures your body’s iron stores. A complete blood count with hemoglobin alone can miss iron deficiency that has not yet progressed to full anemia but may already be affecting cognition, as research has shown in both elderly patients and perimenopausal women.

Are there drugs being developed to remove excess iron from the brain?

Yes. Iron-chelating compounds like deferiprone, clioquinol, and PBT2 are in development for neurodegenerative diseases. Additionally, ferroptosis inhibitors delivered intranasally have shown promise in animal models. None are approved for clinical use in Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s yet, but active research continues.