Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency impairs brain health in measurable, documented ways — affecting memory, mood, cognitive speed, and long-term dementia risk. The brain is a fat-rich organ, and DHA, one of the primary omega-3 fatty acids, constitutes roughly 10% of the brain’s total lipid content. When the body lacks adequate DHA and EPA, the structural integrity of neural cell membranes deteriorates, neuroinflammation increases, and the brain loses some of its capacity to maintain healthy function across the lifespan. In practical terms, someone who has eaten a low-fish, high-processed-food diet for decades is not just missing a supplement — they are likely operating with a brain that is physically and biochemically different from one that has been consistently nourished with adequate omega-3s.

The scale of this problem is larger than most people realize. A 2025 collaborative study found that 76% of the global population does not consume recommended levels of EPA and DHA, making omega-3 deficiency one of the most widespread nutritional gaps in the world. The consequences range from subtle cognitive slowing in otherwise healthy adults to significantly elevated risk of Alzheimer’s disease and depression. This article examines what the research shows about how deficiency affects brain structure, cognitive performance, mental health, and neuroinflammation — and what the evidence suggests about correcting it.

Table of Contents

- What Happens to Brain Structure When Omega-3 Levels Are Too Low?

- How Does Omega-3 Deficiency Raise Dementia and Cognitive Decline Risk?

- Omega-3 Deficiency and Mental Health — Depression, Mood, and Psychiatric Risk

- The Neuroinflammation Connection — Why Diet Composition Matters as Much as Deficiency

- Children and Developmental Deficiency — When the Stakes Are Higher

- Attention, Processing Speed, and the Subtler Cognitive Effects of Low Omega-3

- What the Evidence Suggests About Addressing Omega-3 Deficiency

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Happens to Brain Structure When Omega-3 Levels Are Too Low?

The brain is not abstract. It is a physical organ with a specific chemical composition, and omega-3 fatty acids — particularly DHA — are core structural materials. DHA is a major component of the phospholipid bilayers that make up every neural cell membrane. These membranes govern how neurons communicate, how receptors function, and how efficiently electrical signals travel between brain regions. When DHA is chronically low, cell membranes become less fluid and less responsive, which has downstream effects on virtually every cognitive process. To put this concretely: imagine building a house where 10% of the required materials are consistently missing or replaced with inferior substitutes.

The structure may still stand, but its performance degrades over time — doors stick, insulation fails, wiring becomes unreliable. In the brain, DHA deficiency produces analogous effects. Synaptic transmission slows, receptor sensitivity changes, and the brain’s ability to remodel itself in response to learning — a property known as neuroplasticity — is compromised. DHA is also a critical component of the retina, which is itself neural tissue, so the effects of deficiency are not confined to cognition alone. It is worth noting that the brain does not deplete its DHA stores overnight. The nervous system prioritizes retaining DHA even during periods of low dietary intake, which means deficiency-related structural changes tend to develop gradually. This is precisely why the condition is so easy to overlook — and why it often goes unaddressed until cognitive symptoms are already apparent.

How Does Omega-3 Deficiency Raise Dementia and Cognitive Decline Risk?

The link between omega-3 intake and dementia risk is now supported by substantial longitudinal evidence. An analysis of 48 longitudinal studies involving 103,651 participants found that dietary omega-3 intake was associated with approximately a 20% lower risk of all-cause dementia and cognitive decline. That is a meaningful reduction, comparable in scale to the benefits associated with regular physical exercise. The dose-response relationship is also well-documented: each 0.1 gram per day increase in DHA or EPA intake corresponds to an 8 to 9.9% lower risk of cognitive decline, according to the same body of research. For people already diagnosed with early cognitive impairment or cardiovascular disease — a population at elevated dementia risk — the effects appear even more pronounced. Participants in the ADNI cohort who used omega-3 supplements long-term showed a 64% reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease compared to non-users.

Separately, a dose of 3.36 grams per day of EPA and DHA slowed cognitive aging by approximately 2.5 years in cognitively healthy individuals with coronary artery disease. These are not marginal effects. However, it would be misleading to present omega-3 supplementation as a straightforward cure. The evidence is stronger for prevention than for reversal. Once Alzheimer’s pathology is well-established, omega-3 interventions have shown limited ability to restore function. The implication is that deficiency matters most cumulatively — the brain pays a price for years of inadequate intake that cannot always be fully recovered. This makes early and sustained attention to dietary omega-3 intake particularly important, especially for individuals with a family history of dementia.

Omega-3 Deficiency and Mental Health — Depression, Mood, and Psychiatric Risk

The psychiatric consequences of omega-3 deficiency are increasingly well-characterized. Deficiency is associated with elevated risk of depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorders. Lipidomic studies — which analyze the full spectrum of lipids in blood and tissue — consistently show that people with depression have reduced omega-3 levels compared to healthy controls. This is not simply a correlation that could be explained by poor diet during depressive episodes; the directionality has been examined in Mendelian randomization studies, which use genetic variation to approximate causal inference, and the findings support a genuine mechanistic relationship. For depression specifically, EPA appears to be the more therapeutically relevant omega-3.

Research has found that EPA supplements — particularly formulations where EPA comprises at least 60% of the total EPA plus DHA content, at doses between 200 and 2,200 mg per day of EPA in excess of DHA — are effective against primary depression. This is a more nuanced finding than simply recommending “fish oil.” The ratio of EPA to DHA matters, and high-DHA products may not offer the same antidepressant benefit. A person purchasing a standard fish oil supplement and assuming it addresses their mood symptoms may be using a product that is not optimized for that purpose. In 2025, research further clarified one of the key mechanisms: omega-3 fatty acids act through microglial dysfunction pathways in depressive disorders. Microglia are the brain’s resident immune cells, and when they are chronically activated — as occurs in neuroinflammatory states — they contribute to the neural degradation associated with both depression and cognitive decline. Omega-3s help regulate this process, which connects the mental health and dementia risk findings through a shared biological pathway.

The Neuroinflammation Connection — Why Diet Composition Matters as Much as Deficiency

Omega-3 deficiency rarely occurs in isolation. In most Western dietary patterns, it is accompanied by high intake of omega-6 fatty acids, found in vegetable oils, processed snacks, and fast food. The ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 in the diet has shifted dramatically over the past century — from roughly 4:1 to as high as 20:1 in some populations. This imbalance matters because omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids compete for the same enzymatic pathways. A diet dominated by omega-6 without adequate omega-3 to balance it actively promotes a pro-inflammatory state throughout the body — including in the brain. EPA and DHA modulate neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter function, and neuroplasticity.

When these fatty acids are chronically low and pro-inflammatory omega-6 metabolites dominate, the brain operates in a condition of low-grade chronic inflammation. This is the biochemical environment in which Alzheimer’s plaques accumulate more readily, where depression is harder to treat, and where cognitive function erodes more quickly with age. The tradeoff is not between eating omega-3s and not eating them — it is between a brain that is systematically inflamed and one that has the raw materials to regulate inflammation appropriately. A 2025 dose-response meta-analysis found that each 2,000 mg per day of omega-3 supplementation significantly improved attention and perceptual speed in participants. Attention and processing speed are among the earliest cognitive capacities to deteriorate in neuroinflammatory conditions, which makes their responsiveness to omega-3 supplementation meaningful. It suggests that even in people who have not yet received a dementia diagnosis, correcting deficiency produces measurable cognitive benefit.

Children and Developmental Deficiency — When the Stakes Are Higher

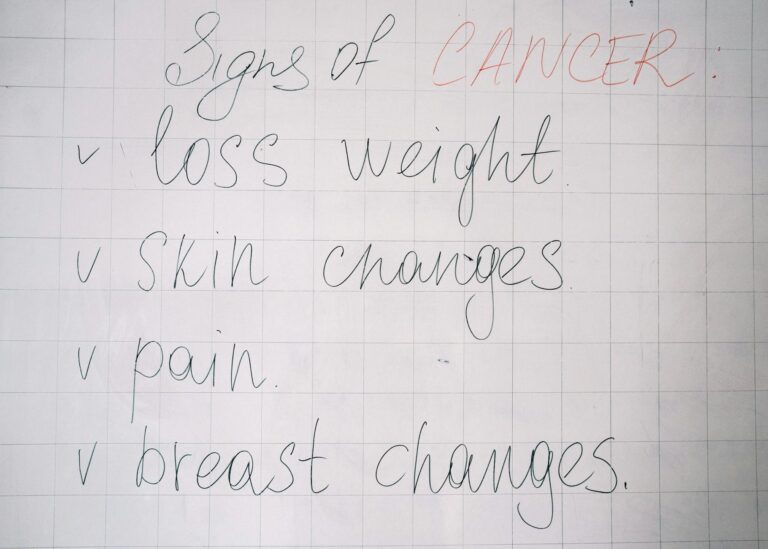

The cognitive consequences of omega-3 deficiency are not limited to aging adults. In children, deficiency correlates with cognitive underperformance and attention deficits. The developing brain is particularly dependent on DHA because it is in a phase of rapid structural expansion — synapse formation, myelination, and cortical organization all depend heavily on adequate DHA availability. A child whose diet consistently lacks omega-3-rich foods is building neural architecture with an inferior supply of essential materials. The association between low omega-3 and ADHD symptoms is particularly well-documented. Children with ADHD consistently show lower blood levels of EPA and DHA than neurotypical peers, and intervention studies using omega-3 supplementation have shown modest but real improvements in attention and behavioral regulation.

This does not mean omega-3 supplements are a substitute for comprehensive ADHD treatment, and the effects in children with clinical diagnoses are smaller than the effects seen in adults with depression. But the relationship is real, and dietary omega-3 intake in childhood is a legitimate factor in cognitive development that is often underappreciated in clinical discussions. One important caveat: the quality and form of omega-3 supplement matters significantly in pediatric contexts. Fish oil in some products has been found to be oxidized — rancid — which not only negates the benefit but may introduce harmful compounds. This is a meaningful concern in a supplement category with variable quality control. For children in particular, dietary sources of omega-3 (fatty fish, algae-based products for those avoiding fish) are generally preferred to relying on supplements of uncertain quality.

Attention, Processing Speed, and the Subtler Cognitive Effects of Low Omega-3

Not all cognitive effects of omega-3 deficiency are dramatic. Many present as subtle degradation in everyday function: slower thinking, difficulty sustaining attention, mildly impaired memory retrieval. These are easy to attribute to aging, stress, or poor sleep — and they are indeed multifactorial. But low omega-3 is an underappreciated contributor to exactly this profile of symptoms.

Research links omega-3 deficiency specifically to poor attention, lower processing speed, and memory difficulties, which are the kinds of complaints that commonly prompt neurological evaluation but often return no definitive diagnosis. The 2025 meta-analysis finding — that 2,000 mg per day of omega-3 improved attention and perceptual speed — is relevant here. Perceptual speed refers to how quickly a person can process and respond to incoming information, a capacity that declines with age and is among the earliest markers of cognitive aging. The fact that it responds to omega-3 supplementation suggests that at least some portion of what presents as “normal aging” in cognitive function may be partly driven by correctable nutritional deficiency. This is worth taking seriously, particularly in people who have never paid attention to their dietary omega-3 intake.

What the Evidence Suggests About Addressing Omega-3 Deficiency

The research on omega-3 fatty acids and brain health has matured considerably over the past decade. What was once a field of promising but inconsistent findings has become a body of evidence strong enough to support practical clinical recommendations. The consistent direction of the data — across studies of dementia risk, depression, attention, cognitive aging, and neuroinflammation — points toward a simple reality: a brain that is chronically deprived of EPA and DHA is a brain operating at a structural and biochemical disadvantage.

Looking forward, research into omega-3s is moving toward greater precision. The optimal doses, ratios of EPA to DHA, duration of supplementation, and timing relative to age and disease stage are all active areas of investigation. The emerging finding that omega-3s act through specific microglial pathways in depression, for example, may eventually allow more targeted interventions. For now, the most defensible recommendation is the one the evidence already supports: consistent, adequate intake of EPA and DHA across the lifespan, beginning well before cognitive symptoms appear.

Conclusion

Omega-3 fatty acid deficiency affects the brain at a structural level — reducing the quality of cell membranes, promoting neuroinflammation, and impairing the neurotransmitter and neuroplasticity functions that underlie cognition and mood. The consequences span from subtle attentional difficulties and slowed processing speed to significantly elevated risk of depression, cognitive decline, and Alzheimer’s disease. The finding that 76% of the global population falls short of recommended EPA and DHA intake places this in proper context: this is not a niche concern for a small at-risk population, but a widespread nutritional gap with documented cognitive consequences.

The evidence does not support treating omega-3 supplementation as a cure or a complete answer to brain health. Diet quality, physical activity, sleep, and cardiovascular health all contribute to cognitive outcomes, and omega-3 intake interacts with all of them. But within that broader picture, the evidence for omega-3s is consistently positive across multiple research methodologies and populations. For individuals concerned about cognitive aging — particularly those with a family history of dementia, a history of depression, or a diet historically low in fatty fish — assessing and addressing omega-3 intake is one of the most evidence-backed steps available.

Frequently Asked Questions

How much EPA and DHA do I need per day for brain health?

Research suggests meaningful cognitive benefits begin at intakes around 1,000 to 2,000 mg of EPA and DHA per day combined. Studies showing slowed cognitive aging used 3.36 grams per day in higher-risk populations. The optimal amount varies by age, health status, and baseline diet, and is best discussed with a physician or registered dietitian.

Is it better to get omega-3s from food or supplements?

Food sources — particularly fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, and sardines — are generally preferred because they come with additional nutrients and avoid the quality control issues that affect some supplement products. That said, for people who do not eat fish regularly, well-sourced fish oil or algae-based DHA supplements are reasonable alternatives. Algae-based products are the primary source of DHA for people following plant-based diets.

Can omega-3 supplementation reverse existing cognitive decline?

The evidence is stronger for prevention than for reversal. Studies show significant risk reduction for cognitive decline in people who consume adequate omega-3s over time, but once Alzheimer’s pathology is well-established, supplementation has shown limited ability to restore function. Earlier intervention produces better outcomes.

Does the ratio of EPA to DHA matter for brain health?

Yes, for specific outcomes. For depression, EPA-dominant formulations — where EPA makes up at least 60% of the combined EPA and DHA content — appear to be more effective than high-DHA products. For general brain structural support and dementia risk reduction, both EPA and DHA appear important. The ratio matters more when targeting specific conditions than for general brain health maintenance.

Are children affected by omega-3 deficiency differently than adults?

Children are in a phase of rapid brain development that is particularly dependent on DHA. Deficiency in childhood is associated with cognitive underperformance and attention difficulties. The stakes are arguably higher because the brain is actively forming its architecture during these years, though the evidence for reversing developmental effects through supplementation is more limited than the evidence for prevention through adequate dietary intake.

Can low omega-3 levels contribute to depression even in otherwise healthy people?

Yes. Lipidomic research consistently finds reduced omega-3 levels in people with depression, and Mendelian randomization studies support a causal relationship — not just a correlation. EPA supplementation at specific doses has been found effective against primary depression in clinical research. However, omega-3 is one factor among many in depression, and supplementation should complement rather than replace evidence-based treatment.