High glycemic foods — white bread, sugary cereals, soda, white rice — cause rapid blood sugar spikes that are now directly linked to a significantly higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease and measurable brain damage, even in people who are not diabetic. A January 2026 University of Liverpool study analyzing genetic data from 357,883 individuals found that people with higher post-meal blood sugar spikes had a 69% greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. What made this finding particularly striking was its specificity: fasting glucose levels, insulin levels, and insulin resistance showed no such link. It was the spikes — the sharp surges that follow a bowl of instant oatmeal or a plate of white pasta — that carried the risk.

This is not a distant, theoretical concern. A separate UK Biobank study published in October 2025, tracking 202,302 participants over 13.25 years, found that people eating high-glycemic-index diets had a 14% increased risk of Alzheimer’s, while those with low-to-moderate GI diets saw a 16% lower risk. During that follow-up period, 2,362 participants developed dementia. The pattern is consistent across studies and populations: what you eat after breakfast may matter more to your brain than your doctor’s fasting blood sugar test suggests. This article examines how blood sugar spikes damage the hippocampus, reduce critical brain growth factors, and contribute to what researchers now call “Type 3 Diabetes.” It also covers practical steps for shifting to a lower-glycemic diet — and the limitations of what we currently know.

Table of Contents

- How Do Blood Sugar Spikes From High Glycemic Foods Damage Your Memory?

- The BDNF Connection — Why Sugar Starves Your Brain of Its Growth Factor

- “Type 3 Diabetes” — When Your Brain Becomes Insulin Resistant

- Practical Swaps — Moving From High-GI to Low-GI Eating for Brain Health

- What These Studies Cannot Tell Us — Limitations and Open Questions

- The Meal Timing Factor — Why Post-Meal Spikes Matter More Than Fasting Levels

- Where the Research Is Heading

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Blood Sugar Spikes From High Glycemic Foods Damage Your Memory?

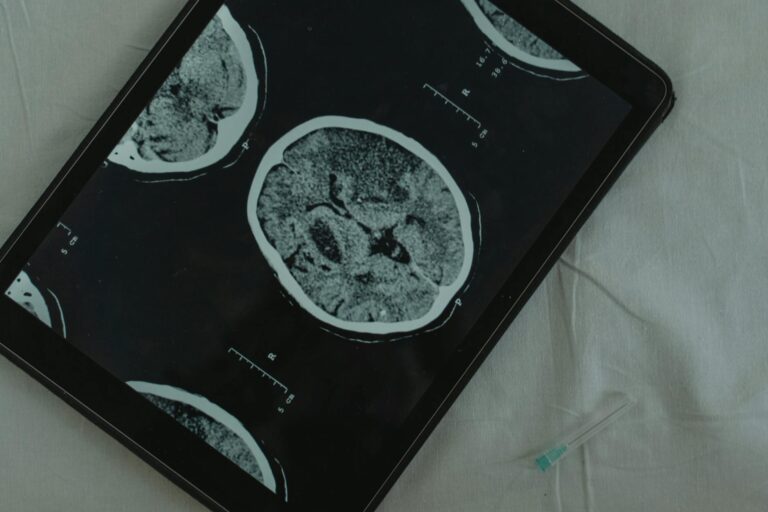

The hippocampus — the brain‘s primary memory center — turns out to be unusually vulnerable to glucose fluctuations. A landmark study published in PNAS found that even among healthy, non-diabetic elderly people, reduced glucose tolerance was significantly correlated with smaller hippocampal volume and poorer memory performance. The damage was anatomically specific: no associations were found with other brain regions. Your hippocampus, essentially, is the canary in the coal mine for blood sugar problems. This vulnerability extends well below the diabetic threshold. Research from the PATH Through Life Study, published in PLOS ONE, found that fasting plasma glucose levels in the high-normal range — below 6.1 mmol/L, meaning clinically “not diabetic” — were associated with greater atrophy of the hippocampus and amygdala.

In other words, a person whose doctor says their blood sugar is fine may still be losing brain volume. Consider someone who eats white toast with jam every morning and a sandwich on white bread for lunch. Their fasting glucose might look perfectly normal at a checkup, but those repeated post-meal spikes could be quietly shrinking the part of their brain responsible for forming new memories. For people with established Type 2 diabetes, the picture is more severe. Research published in eLife showed that individuals with T2D had 4.4% more hippocampal atrophy compared to non-diabetic individuals, corresponding to approximately 4 to 5 years of additional brain aging. That is not a subtle difference — it is the equivalent of your brain being half a decade older than it should be.

The BDNF Connection — Why Sugar Starves Your Brain of Its Growth Factor

One of the most important mechanisms connecting blood sugar spikes to cognitive decline involves brain-derived neurotrophic factor, or BDNF. Think of BDNF as fertilizer for your neurons — it supports memory-associated neuroplasticity, cell survival, and the growth of new synaptic connections. Without adequate BDNF, your brain struggles to form and retain memories, adapt to new information, and repair itself. A well-cited study found that a high-fat, refined sugar diet reduced hippocampal BDNF levels and impaired spatial learning performance in just two months. Two months of poor eating was enough to measurably change brain chemistry. Separately, research published in Nature Scientific Reports showed that high plasma glucose levels negatively influence BDNF output from the brain, and that BDNF levels correlate with insulin resistance.

The relationship runs in both directions: high blood sugar suppresses BDNF, and low BDNF makes the brain more vulnerable to metabolic damage. However, this is not purely a one-way street. Studies on carbohydrate-restricted diets found that reducing carb intake increased basal BDNF protein levels by 20%, and by 38% when combined with high-intensity interval training. This suggests the damage is at least partially reversible — but the caveat matters. These improvements were seen in controlled study conditions. Someone who has been eating a high-GI diet for decades and already has significant hippocampal atrophy should not expect a dietary change alone to fully restore lost brain volume. The earlier the intervention, the more there is to protect.

“Type 3 Diabetes” — When Your Brain Becomes Insulin Resistant

Researchers have increasingly proposed that Alzheimer’s disease is linked to central nervous system-specific insulin signaling deficiencies — a concept sometimes called “Type 3 Diabetes.” First proposed in 2005, this framework argues that the brain can develop its own form of insulin resistance, independent of what is happening in the rest of the body. When brain insulin signaling fails, glucose uptake drops, amyloid-beta clearance slows down (allowing the plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s to accumulate), and tau hyperphosphorylation increases — another hallmark of the disease. A 2025 MDPI review and a systematic review published in PMC both support this framework with growing evidence, though it is important to note that “Type 3 Diabetes” is not yet an official diagnostic category. No clinician will write it on a chart. But the underlying biology is well-documented: insulin resistance in the brain creates conditions that look remarkably like the early stages of Alzheimer’s. For example, a person who has been eating high-glycemic meals for years may have perfectly normal peripheral insulin sensitivity — their muscles and liver handle glucose fine — but their brain cells may already be struggling to take up the glucose they need to function.

A meta-analysis further underscored the complexity of this relationship. HbA1c variability — meaning not just high blood sugar, but erratic swings between high and low — and longer diabetes duration were each significantly associated with higher dementia risk. Hypoglycemia episodes were linked to a 49% higher risk of all-cause dementia and a 31% higher risk of Alzheimer’s specifically. This is a critical point: the goal is not to drive blood sugar as low as possible. Crashes may be as dangerous as spikes. The brain needs stable, steady glucose — not too much, not too little.

Practical Swaps — Moving From High-GI to Low-GI Eating for Brain Health

The glycemic index scores foods from 0 to 100 based on how quickly they raise blood sugar. Foods below about 55 are considered low-GI, while those above 70 are high-GI. The UK Biobank study found protective effects against dementia specifically below a dietary GI of 49.3 — a threshold worth keeping in mind. High-GI foods that cause rapid blood sugar spikes include white bread, white rice, potatoes, sugary cereals, candy, and soda. Low-GI alternatives that release glucose slowly include whole grains, legumes, most fruits, nuts, and non-starchy vegetables. The practical tradeoffs matter here. Swapping white rice for brown rice or cauliflower rice is straightforward, but brown rice takes longer to cook and has a chewier texture that not everyone prefers.

Replacing white bread with genuine whole-grain bread works well, but many “whole wheat” breads at the supermarket have glycemic indexes nearly as high as white bread — you need to check for intact grains or look for dense, seeded varieties. Legumes like lentils and chickpeas are among the lowest-GI staples available and are inexpensive, but they require preparation time and can cause digestive discomfort for people not accustomed to them. The best diet change is one a person will actually sustain for years, not one that looks perfect on paper but gets abandoned in three weeks. One important comparison: the difference between glycemic index and glycemic load. A food’s GI measures how fast it raises blood sugar, but glycemic load accounts for portion size. Watermelon, for example, has a high GI (around 72) but a low glycemic load because a typical serving contains relatively little carbohydrate. Focusing exclusively on GI can lead people to unnecessarily eliminate foods that have minimal real-world impact on blood sugar.

What These Studies Cannot Tell Us — Limitations and Open Questions

The January 2026 University of Liverpool study is powerful because it used Mendelian Randomization, a method that leverages genetic variation to approximate a randomized controlled trial. This makes its findings more robust than typical observational studies. But Mendelian Randomization has its own limitations — it assumes the genetic variants used as instruments affect Alzheimer’s risk only through their effect on post-meal blood sugar, and violations of that assumption could bias results. The researchers were transparent about this, but it means the 69% figure, while striking, should be treated as a strong signal rather than a definitive causal proof. The UK Biobank study, for its part, relied on dietary questionnaires — people reporting what they eat. Self-reported diet data is notoriously unreliable.

People underestimate sugar intake, forget snacks, and report what they think they should be eating rather than what they actually eat. The 14% increased risk and 16% decreased risk figures are adjusted for confounders, but unmeasured factors (sleep quality, stress levels, social isolation) could still influence the results. Perhaps the biggest open question is timing. We know that blood sugar spikes are associated with brain damage, but we do not know exactly when intervention stops being fully effective. Can a 70-year-old with decades of high-GI eating meaningfully reduce their Alzheimer’s risk by changing their diet now? The BDNF research suggests some reversibility, but lost hippocampal volume may not return. For caregivers and family members, this is worth discussing honestly: dietary changes are worth making at any age, but earlier is almost certainly better.

The Meal Timing Factor — Why Post-Meal Spikes Matter More Than Fasting Levels

The University of Liverpool finding that only post-meal blood sugar — not fasting glucose, not insulin levels, not insulin resistance — was linked to Alzheimer’s risk has a practical implication that most people overlook. Standard medical checkups typically measure fasting blood sugar. A person could pass every fasting glucose test for years while experiencing damaging post-meal spikes that never get detected.

Someone who eats a bagel with juice for breakfast might spike to 180 mg/dL an hour later, but by the time they sit in a doctor’s office the next morning after fasting overnight, their reading looks normal. This suggests that people concerned about brain health may want to specifically monitor post-meal glucose, either through continuous glucose monitors or by requesting a post-prandial glucose test at their next appointment. It also means that strategies targeting post-meal spikes — eating protein or fat before carbohydrates, taking a short walk after meals, choosing lower-GI carbohydrate sources — may be more relevant to brain health than overall calorie counting or even total carbohydrate restriction.

Where the Research Is Heading

The convergence of large genetic studies, long-term cohort data, and molecular research on BDNF and brain insulin signaling is building a case that dietary glycemic management may become a standard recommendation in dementia prevention — much the way blood pressure management became a cornerstone of stroke prevention decades ago. The concept of Alzheimer’s as “Type 3 Diabetes” continues to gain traction in the research community, and if future clinical trials confirm that lowering post-meal glucose spikes reduces Alzheimer’s incidence, it could reshape both dietary guidelines and pharmaceutical development. For now, the evidence is strong enough to act on but not yet definitive enough to make absolute promises.

No single dietary change guarantees protection against Alzheimer’s. But the data consistently points in one direction: keeping blood sugar stable, particularly after meals, appears to protect the brain structures most critical for memory. That is a message worth taking seriously, especially given that the intervention — eating fewer refined carbohydrates — carries essentially no risk and considerable general health benefits.

Conclusion

The research linking high glycemic foods to memory loss and Alzheimer’s risk has reached a level of consistency that is difficult to ignore. The January 2026 University of Liverpool study, with its 357,883-person genetic analysis showing a 69% higher Alzheimer’s risk from post-meal blood sugar spikes, joins a growing body of evidence including the UK Biobank’s 202,302-participant cohort study, BDNF research, and hippocampal imaging studies. Together, they paint a picture of a brain that is far more sensitive to dietary sugar than most people realize — and far more damaged by it than standard medical tests reveal.

The practical takeaway is not to panic or to adopt an extreme diet. It is to make informed, sustainable shifts: replace high-GI staples with lower-GI alternatives, pay attention to post-meal blood sugar rather than only fasting levels, and recognize that the brain’s memory centers are quietly affected by every glucose spike. For those caring for someone with dementia or concerned about their own risk, these are changes that cost nothing, carry no side effects, and align with what the best available science is telling us.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can blood sugar spikes cause memory problems even if I am not diabetic?

Yes. Research published in PNAS found that even healthy, non-diabetic elderly people with reduced glucose tolerance had smaller hippocampal volume and poorer memory performance. A separate PATH Through Life Study found that fasting glucose in the high-normal range — well below the diabetic threshold — was associated with brain atrophy. You do not need a diabetes diagnosis to be at risk.

What is the single most important dietary change for protecting brain health from blood sugar damage?

Based on the research, reducing post-meal blood sugar spikes appears to be the most impactful change. This means replacing high-GI foods like white bread, white rice, and sugary cereals with low-GI alternatives such as whole grains, legumes, nuts, and non-starchy vegetables. The UK Biobank study found protective effects at a dietary glycemic index below 49.3.

What is “Type 3 Diabetes” and should I be worried about it?

“Type 3 Diabetes” is a research framework proposing that Alzheimer’s disease involves insulin resistance specific to the brain. When brain insulin signaling breaks down, glucose uptake drops, amyloid-beta plaques accumulate, and tau proteins become hyperphosphorylated — all hallmarks of Alzheimer’s. It is not yet an official diagnostic category, but the underlying biology is supported by growing evidence from multiple reviews and meta-analyses.

Is it too late to change my diet if I am already older?

It is worth changing at any age, but earlier intervention is likely more effective. Research shows that low-carb diets can increase BDNF protein levels by 20 to 38%, suggesting some reversibility. However, hippocampal volume lost to years of high blood sugar may not fully return. The goal shifts from prevention to slowing further decline.

Are blood sugar crashes also bad for the brain?

Yes. A meta-analysis found that hypoglycemia episodes were linked to a 49% higher risk of all-cause dementia and a 31% higher risk of Alzheimer’s specifically. The brain needs stable glucose — not too high, not too low. This is why extreme low-carb diets or skipping meals entirely may not be the right approach for everyone.

Does my regular blood test catch the kind of blood sugar problems linked to Alzheimer’s?

Likely not. The University of Liverpool study found that only post-meal blood sugar spikes — not fasting glucose — were linked to Alzheimer’s risk. Standard checkups typically measure fasting glucose, which can appear normal even in people who experience significant post-meal spikes. Ask your doctor about post-prandial glucose testing or consider a continuous glucose monitor if brain health is a concern.