Methylfolate — the naturally active form of vitamin B9 — is the better choice for brain health in most people, and the reason comes down to basic biochemistry. Unlike synthetic folic acid, methylfolate (also called 5-MTHF) crosses the blood-brain barrier directly and participates in the production of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine without requiring any enzymatic conversion. This matters enormously because up to 40% of the U.S. population carries a genetic variant that impairs their ability to convert folic acid into the form the brain can actually use. For someone caring for a parent with early cognitive decline, or noticing their own memory slipping, the distinction between these two forms of the same vitamin is not academic — it could influence whether supplementation helps or does nothing at all.

That said, the full picture is more complicated than simply swapping one supplement for another. Research shows that folic acid supplementation taken alone may actually have unfavorable effects on cognitive health, while combining it with vitamins B6 and B12 counteracts those risks. A 2024 UK Biobank study involving over 466,000 participants confirmed this pattern. The benefits of folate supplementation are also most pronounced in specific populations: people with elevated homocysteine levels, existing folate deficiency, or mild cognitive impairment. This article breaks down exactly what folate and folic acid are, why the MTHFR gene matters so much, what the clinical research actually shows about dementia risk, and how to make a practical decision about supplementation.

Table of Contents

- What Is the Actual Difference Between Folate and Folic Acid for Your Brain?

- The MTHFR Gene Variant and Why It Changes Everything About Folate Supplementation

- What the Dementia and Cognitive Decline Research Actually Shows

- Why You Should Not Take Folic Acid Alone — The B-Vitamin Synergy Problem

- Folate Deficiency and the Brain — Damage Beyond Memory Loss

- Folate’s Role in Depression and Mental Health — A Parallel Pathway to Cognitive Protection

- Where Folate Research Is Heading and What It Means for Dementia Prevention

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Actual Difference Between Folate and Folic Acid for Your Brain?

Folate is the naturally occurring form of vitamin B9, found in foods like leafy greens, legumes, and liver. Folic acid is the synthetic version created for supplements and fortified foods like enriched bread and cereal. While they are often discussed interchangeably, the body processes them very differently. When you eat spinach, your body absorbs folate and converts it relatively efficiently into methylfolate (5-MTHF), the biologically active form. When you take a folic acid pill, your body must run it through a multi-step conversion process, with the final and rate-limiting step depending on an enzyme encoded by the MTHFR gene. Methylfolate is the form that actually crosses the blood-brain barrier and serves as a required cofactor for neurotransmitter synthesis. The brain-specific role of methylfolate is worth understanding in detail.

It is essential for converting homocysteine to methionine, which in turn produces SAMe (S-adenosyl-methionine) — one of the most important methyl donors in the brain. SAMe is critical for manufacturing serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Without adequate methylfolate, this entire cascade slows down. Think of it like a factory assembly line: methylfolate is a key part that keeps the line moving. Folic acid is the raw material that needs to be machined into that part first — and in a significant portion of the population, the machine that does the conversion is running at reduced capacity. A helpful comparison: if you gave two people the same 400 mcg folic acid supplement, one with normal MTHFR function and one with two copies of the C677T variant, the second person would convert it at roughly 30% of the efficiency of the first. They would get far less usable methylfolate from the same pill. This is not a rare scenario — it describes somewhere between 8% and 20% of Americans.

The MTHFR Gene Variant and Why It Changes Everything About Folate Supplementation

The MTHFR gene has received increasing attention in both psychiatric and neurological research, and for good reason. The C677T variant of this gene is remarkably common: 20% to 40% of Americans carry one copy, which reduces enzyme function to about 65% of normal. Those with two copies — 8% to 20% of the population — operate at as low as 30% of normal MTHFR enzyme capacity. For these individuals, taking synthetic folic acid is an inefficient way to support brain health because the bottleneck is in the conversion step itself. The clinical implications extend well beyond inconvenience. MTHFR polymorphisms have been identified as a recognized risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

They have also been associated with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, autism, and ADHD. This does not mean carrying the variant guarantees any of these conditions, but it does mean the metabolic pathway most affected — the one that governs methylation and neurotransmitter production — is the same pathway implicated in these disorders. A person with two copies of C677T who relies solely on folic acid supplementation may be getting a fraction of the brain support they think they are. However, here is an important caveat: most people do not know their MTHFR status. Genetic testing is available but not routinely ordered. If you are considering folate supplementation specifically for cognitive protection and you have not been tested, methylfolate (5-MTHF) is the more universally effective option — it bypasses the MTHFR conversion step entirely and works regardless of your genetic profile. There is no scenario in which methylfolate is less effective than folic acid for someone with reduced MTHFR function, but there are many scenarios in which folic acid falls short.

What the Dementia and Cognitive Decline Research Actually Shows

The link between folate status and dementia risk is now supported by large-scale population data. A UK Biobank study published in the Journals of Gerontology in 2024 found that individuals with low folate concentrations (at or below 11.8 nmol/L) had a nearly 90% higher risk of developing dementia compared to those with normal levels. Separately, research highlighted by the Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research found that adults consuming 400 mcg or more of folic acid per day had a 55% reduction in the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical trials have added further weight. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that 800 mcg per day of folic acid over three years improved global cognitive functioning, memory storage, and information-processing speed in healthy elderly adults who had elevated homocysteine levels — a key detail, because the benefits were specific to that subgroup.

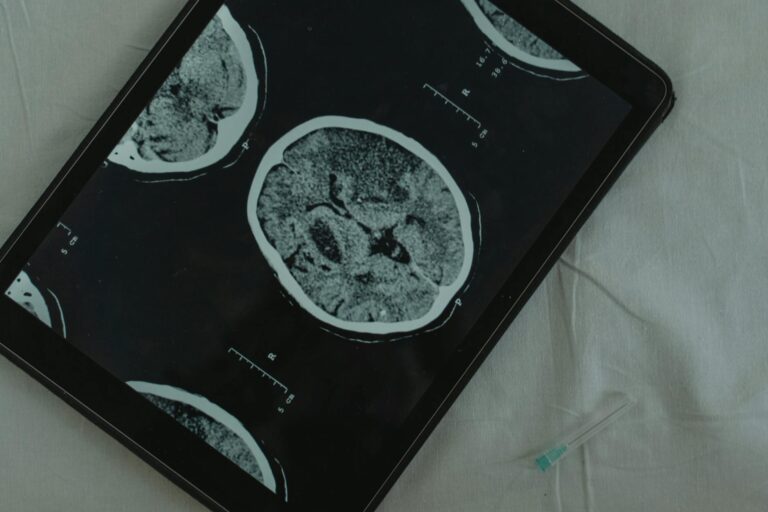

A 2024 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials published in the Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics found that 400 mcg per day of folic acid significantly improved cognitive function and reduced inflammatory markers (IL-6 and TNF-alpha) in elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment. And a two-year clinical trial showed that B-vitamin supplementation including folate reduced global and regional brain atrophy as measured by MRI in older adults. These findings are encouraging, but they come with an important limitation. A 2024 meta-analysis published in Nutrients found that folate-based supplementation produced significant cognitive benefits in countries without mandatory folic acid food fortification — but the benefits were not statistically significant in countries like the United States, where flour and grain products are already fortified with folic acid. This suggests that if you are already getting baseline folate through fortified foods, additional folic acid supplementation may offer diminishing returns. For Americans, this makes the case for methylfolate over folic acid even stronger, since methylfolate provides the active form directly without adding to the pool of unconverted synthetic folic acid.

Why You Should Not Take Folic Acid Alone — The B-Vitamin Synergy Problem

One of the most consequential findings from recent research is that folic acid supplementation taken in isolation may not just be ineffective — it could be counterproductive. The same UK Biobank study that documented the dementia risk associated with low folate also found that folic acid supplementation alone may have unfavorable implications for cognitive health. A separate U.S. community-based study found that high folic acid supplementation taken without other B vitamins was associated with accelerated cognitive decline. The solution, according to the evidence, is straightforward: combine folic acid or methylfolate with vitamins B6 and B12. The UK Biobank data showed that combining folic acid with other B vitamins counteracted the adverse effects seen with folic acid alone. This makes biological sense.

Folate, B6, and B12 all participate in the homocysteine metabolism pathway. B12 is a direct cofactor alongside methylfolate in converting homocysteine to methionine. Without adequate B12, methylfolate can become “trapped” in a form the body cannot recycle. B6 handles homocysteine through an alternative pathway. Supplementing one without the others creates an imbalance. The practical takeaway is to avoid purchasing folic acid in isolation for brain health purposes. Look for a B-complex supplement that includes methylfolate (or at minimum folic acid), B12 (ideally as methylcobalamin), and B6 (as pyridoxal-5-phosphate or pyridoxine). This three-part combination has the strongest evidence base for cognitive protection and is consistent with the formulations used in the clinical trials that demonstrated reduced brain atrophy and improved cognitive scores.

Folate Deficiency and the Brain — Damage Beyond Memory Loss

A 2025 review of the literature outlined what happens in the brain when dietary folate is chronically insufficient. The consequences go beyond cognitive symptoms: folate deficiency leads to increased lipid peroxidation, decreased antioxidant defenses, increased neuronal death, DNA damage, and gliosis (the proliferation of glial cells in damaged brain areas, a marker of neuroinflammation). These are not subtle biochemical footnotes — they describe a brain under active assault from oxidative stress and impaired repair mechanisms. This is particularly concerning for older adults, who are more likely to have reduced folate absorption due to age-related changes in the gut, medication interactions (metformin and certain anticonvulsants are known to deplete folate), and dietary patterns that may lack sufficient leafy greens and legumes.

A person taking metformin for type 2 diabetes while also carrying one or two copies of the MTHFR C677T variant could be facing a compounded deficit that neither their doctor nor they are aware of. One warning worth emphasizing: the tolerable upper intake level for folic acid from supplements and fortified foods is 1,000 mcg per day. Exceeding this level is not recommended, in part because high doses of unmetabolized folic acid circulating in the blood have been flagged in some research as potentially problematic — particularly for individuals with low B12 status, where excess folic acid may mask a B12 deficiency and allow neurological damage to progress undetected. This upper limit applies to synthetic folic acid specifically; methylfolate does not carry the same concern about unmetabolized forms accumulating in the bloodstream.

Folate’s Role in Depression and Mental Health — A Parallel Pathway to Cognitive Protection

The connection between folate and mental health reinforces why this vitamin matters so much for brain function broadly. Patients treated with L-methylfolate for treatment-resistant depression experienced a 25% reduction in depression scores compared to baseline. Research has also shown that L-methylfolate supplementation is associated with increased cortical thickness and altered limbic connectivity — structural brain changes that suggest real neurological impact, not just symptom masking. The American Psychiatric Association recognizes folate as adjunctive therapy to antidepressant medication, a significant endorsement from a major professional body.

For caregivers concerned about a loved one’s cognitive health, this overlap between depression and dementia is worth noting. Depression in older adults is both a risk factor for and an early symptom of dementia. If folate insufficiency contributes to both conditions through the same neurotransmitter pathway, addressing it could provide benefits on both fronts simultaneously. A person whose worsening mood is attributed to “just getting older” might in fact be folate-depleted and responsive to methylfolate supplementation — but only if someone thinks to check.

Where Folate Research Is Heading and What It Means for Dementia Prevention

The research trajectory points toward greater precision in how folate is recommended for brain health. Current evidence already suggests that the standard RDA of 400 mcg per day may not be sufficient for individuals with chronic central nervous system disorders. Future guidelines may differentiate recommendations based on MTHFR genotype, homocysteine levels, and existing cognitive status — a shift from one-size-fits-all dosing to targeted nutritional intervention.

The growing recognition that methylfolate is functionally superior to folic acid for brain applications is likely to change supplement formulations over the coming years. Methylfolate is already widely available, but it remains less common in mass-market multivitamins than synthetic folic acid, largely because folic acid is cheaper to manufacture. As awareness of MTHFR variants grows and more clinicians incorporate folate status into cognitive assessments, the shift toward methylfolate as the default supplemental form for brain health appears inevitable. For individuals and families dealing with cognitive decline now, the evidence is already strong enough to act on.

Conclusion

The weight of current research favors methylfolate over synthetic folic acid for brain health, particularly for the estimated 40% of the population with reduced MTHFR enzyme function. Methylfolate crosses the blood-brain barrier directly, supports neurotransmitter synthesis without requiring enzymatic conversion, and avoids the risks associated with unmetabolized folic acid accumulation. The evidence is clearest for people with elevated homocysteine, existing folate deficiency, or mild cognitive impairment — but given the prevalence of MTHFR variants and the low risk profile of methylfolate, it is a reasonable choice for anyone supplementing with brain health in mind. The most important practical lesson from the research is to never take folic acid alone for cognitive protection.

Combine it — or preferably methylfolate — with vitamins B12 and B6, as the synergy between these three B vitamins is what drives the observed benefits in clinical trials. Talk to a physician about checking homocysteine levels and, if possible, MTHFR status. Ensure dietary folate through leafy greens, legumes, and other whole food sources. And for those already navigating a dementia diagnosis in the family, understand that optimizing folate status is one modifiable factor in a landscape where modifiable factors are few and precious.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I get enough folate from food alone to protect my brain?

Possibly, if your diet is rich in leafy greens, legumes, and other folate-dense foods, and your MTHFR function is normal. However, research showing cognitive benefits typically involves supplemental doses of 400 to 800 mcg per day, which is difficult to achieve through diet alone consistently. Food-sourced folate is also less bioavailable than supplemental methylfolate.

Should I get tested for the MTHFR gene variant?

Testing is available through many labs and direct-to-consumer genetic services. It is most useful if you are considering folate supplementation for cognitive or mental health reasons, have a family history of dementia or depression, or have elevated homocysteine levels. However, even without testing, choosing methylfolate over folic acid is a reasonable precaution since it works regardless of your genetic status.

Is folic acid in fortified foods a problem?

Not necessarily. Mandatory folic acid fortification in the U.S. has been effective at reducing neural tube defects. However, for brain health specifically, a 2024 meta-analysis found that additional folate supplementation showed significant cognitive benefits only in countries without mandatory fortification, suggesting Americans may already have baseline coverage. The concern is more about relying solely on folic acid without B12 and B6 alongside it.

How much methylfolate should I take for brain health?

Most clinical trials showing cognitive benefits used doses between 400 and 800 mcg per day. The RDA for adults is 400 mcg DFE per day, though researchers have noted this may not be sufficient for individuals with central nervous system disorders. The tolerable upper intake level of 1,000 mcg per day applies to synthetic folic acid specifically. Consult a healthcare provider for personalized dosing, especially if you take medications that interact with folate.

Can folate supplementation reverse cognitive decline that has already started?

The evidence is most encouraging for slowing decline rather than reversing it. A two-year trial showed B-vitamin supplementation including folate reduced brain atrophy in older adults, and a meta-analysis found benefits for elderly patients with mild cognitive impairment. Benefits are strongest when homocysteine levels are elevated. There is currently no evidence that folate supplementation reverses moderate or advanced dementia.

Does folate help with depression in addition to cognitive decline?

Yes. L-methylfolate has been shown to reduce depression scores by 25% in patients with treatment-resistant depression, and the American Psychiatric Association recognizes folate as adjunctive therapy alongside antidepressants. Since depression in older adults is both a risk factor for and early symptom of dementia, addressing folate status may benefit both conditions through the same neurotransmitter pathway.