Protein clearance fails in Alzheimer’s disease primarily because the brain’s waste removal systems””the glymphatic system, autophagy, and proteasome pathways””become impaired with age and disease progression, allowing toxic proteins like amyloid-beta and tau to accumulate faster than they can be removed. This failure isn’t a single breakdown but a cascade of interconnected dysfunctions: sleep disruption reduces glymphatic drainage by up to 40%, aging mitochondria can’t power cellular cleanup machinery, and the very proteins that need clearing begin damaging the systems designed to remove them. Consider a 68-year-old patient whose brain produces roughly the same amount of amyloid-beta as a healthy 30-year-old, yet develops plaques””the difference isn’t overproduction but a clearance rate that has declined by nearly half over those decades. Understanding why these systems fail matters enormously for prevention and treatment strategies.

For years, pharmaceutical companies focused almost exclusively on reducing amyloid production, spending billions on drugs that ultimately failed in clinical trials. The emerging consensus recognizes that enhancing clearance may prove equally or more important than blocking production. This article examines the specific mechanisms behind clearance failure, from the newly discovered glymphatic system to cellular autophagy, and explores what research reveals about preserving and potentially restoring these critical functions. We’ll also address the practical implications for sleep, exercise, and lifestyle factors that influence your brain’s ability to take out its own trash.

Table of Contents

- How Does the Brain’s Glymphatic System Clear Toxic Proteins?

- Why Cellular Autophagy Declines With Age and Disease

- The Role of Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Clearance Failure

- How Sleep Quality Directly Impacts Protein Waste Removal

- When Inflammation Overwhelms the Brain’s Cleanup Crews

- The Emerging Role of Peripheral Organs in Brain Protein Clearance

- How to Prepare

- How to Apply This

- Expert Tips

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

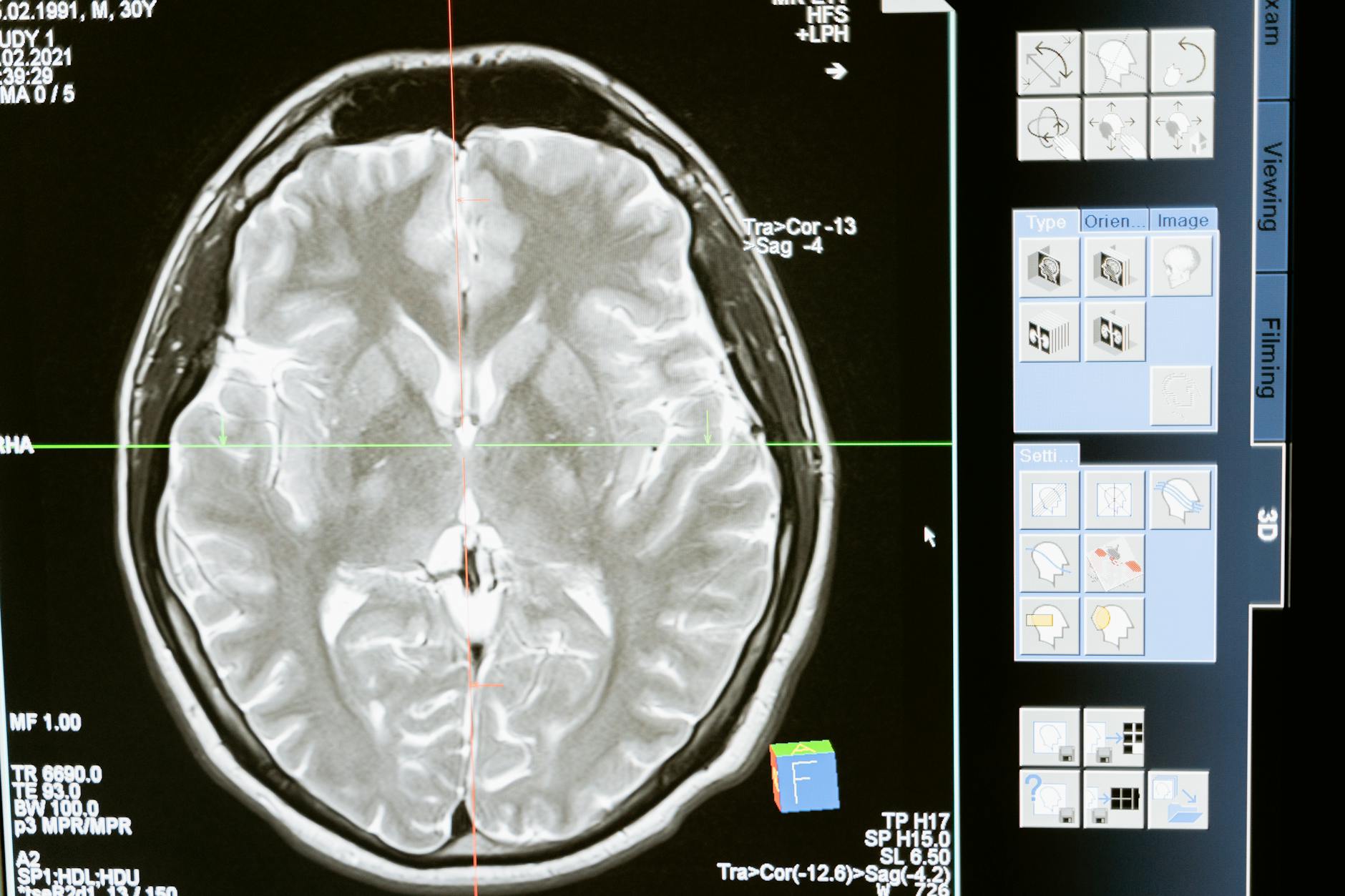

How Does the Brain’s Glymphatic System Clear Toxic Proteins?

The glymphatic system, discovered only in 2012 by Dr. Maiken Nedergaard’s team at the University of Rochester, functions as the tau/” title=”How Brain Cells Normally Clear Amyloid and Tau”>brain‘s dedicated waste removal network. Unlike the rest of the body, which relies on the lymphatic system, the brain uses cerebrospinal fluid flowing along channels surrounding blood vessels to flush out metabolic waste, including amyloid-beta and tau proteins. This fluid moves through the brain’s interstitial spaces, collecting debris and draining it through pathways that ultimately connect to the body’s lymphatic system at the base of the skull. What makes this system remarkable””and vulnerable””is its dependence on sleep. During deep non-REM sleep, brain cells shrink by approximately 60%, dramatically expanding the interstitial channels and allowing cerebrospinal fluid flow to increase tenfold compared to waking states.

A single night of sleep deprivation measurably increases amyloid-beta levels in healthy adults. Chronic poor sleep creates a vicious cycle: accumulated proteins disrupt sleep architecture, which further impairs clearance, which accelerates accumulation. Comparing two 70-year-olds, one with consistent deep sleep and one with fragmented sleep patterns, the latter may show amyloid accumulation equivalent to someone a decade older. However, the glymphatic system doesn’t operate in isolation, and enhancing it alone won’t solve clearance problems if other mechanisms are compromised. Individuals with cardiovascular disease show reduced glymphatic function even with adequate sleep, because arterial stiffness impairs the pulsations that help drive fluid movement. This limitation explains why addressing Alzheimer’s risk requires a systems-level approach rather than focusing on any single pathway.

- —

Why Cellular Autophagy Declines With Age and Disease

autophagy“”literally “self-eating”””represents the cell’s internal recycling program, where damaged proteins and organelles get enclosed in membranes and delivered to lysosomes for breakdown. This process is essential for clearing misfolded proteins before they aggregate, and neurons are particularly dependent on efficient autophagy because they cannot dilute toxic proteins through cell division like other tissues can. In healthy young neurons, autophagy maintains a steady state where protein production and degradation remain balanced. Age-related autophagy decline stems from multiple factors converging simultaneously. Lysosomal function deteriorates as these organelles accumulate lipofuscin””undegradable cellular waste that impairs their ability to break down new material. Meanwhile, the proteins that initiate autophagy, particularly beclin-1, decrease with age, and the cellular energy required to power the process becomes scarcer as mitochondrial function wanes.

Research in mouse models demonstrates that animals genetically engineered with enhanced autophagy show dramatically reduced protein aggregation and extended cognitive function. The critical limitation here involves timing: autophagy enhancement appears most protective early in disease progression. Once large protein aggregates have formed, standard autophagy cannot process them efficiently. These aggregates can actually damage lysosomes when cells attempt to digest them, releasing partially degraded toxic fragments and inflammatory signals. This is why some experimental autophagy-enhancing drugs showed disappointing results in patients with established Alzheimer’s””the intervention came too late in the cascade. If autophagy-supporting strategies are implemented only after significant symptoms appear, benefits may be limited compared to preventive approaches begun decades earlier.

- —

The Role of Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown in Clearance Failure

The blood-brain barrier, formed by tightly sealed endothelial cells lining brain blood vessels, does far more than keep harmful substances out””it actively participates in protein clearance through specialized transport receptors. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) on these endothelial cells binds amyloid-beta and shuttles it from brain tissue into the bloodstream for elimination by the liver and kidneys. In young, healthy individuals, this transvascular clearance pathway handles a substantial portion of amyloid removal. Barrier breakdown in Alzheimer’s disease disrupts this clearance route while simultaneously creating new problems. When endothelial tight junctions loosen””visible on advanced MRI as increased permeability””the coordinated transport of amyloid-beta becomes chaotic and inefficient.

Blood proteins that shouldn’t enter the brain leak in, triggering inflammatory responses that further damage clearance mechanisms. Autopsy studies reveal that blood-brain barrier breakdown often precedes detectable amyloid plaques, suggesting it may be an initiating factor rather than merely a consequence of disease. A specific example illustrates this relationship: carriers of the APOE4 gene variant, the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s, show accelerated blood-brain barrier breakdown beginning in middle age, detectable through specialized imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. These individuals demonstrate reduced LRP1 expression and correspondingly impaired amyloid clearance across the barrier. understanding this mechanism has led researchers to investigate whether protecting barrier integrity might preserve clearance function, with several compounds currently in early-stage trials targeting endothelial health.

- —

How Sleep Quality Directly Impacts Protein Waste Removal

Optimizing sleep represents the most immediately actionable intervention for supporting protein clearance, but the relationship involves specific sleep stages rather than total sleep duration alone. Slow-wave deep sleep, characterized by synchronized neuronal firing patterns visible on EEG as delta waves, creates the conditions necessary for maximal glymphatic flow. An individual sleeping eight hours but spending minimal time in deep sleep may clear proteins less effectively than someone sleeping six hours with normal sleep architecture. The comparison between natural sleep and sedative-induced unconsciousness reveals important distinctions. Certain sleep medications, particularly older benzodiazepines and antihistamines, suppress slow-wave sleep while increasing total sleep time””potentially worsening clearance despite improving subjective sleep quality.

Conversely, some newer medications and non-pharmacological approaches specifically enhance deep sleep. One study found that acoustic stimulation synchronized to brain waves during sleep increased slow-wave activity by 25% and improved morning measures of amyloid clearance in older adults. The tradeoff between sleep duration and sleep timing also matters considerably. Research on shift workers and individuals with irregular schedules shows that sleeping during daylight hours, even for adequate duration, results in less slow-wave sleep and presumably less effective clearance than nighttime sleep aligned with circadian rhythms. This finding has profound implications for caregivers, healthcare workers, and others whose schedules conflict with biological night. For these individuals, maximizing sleep quality through environment optimization and timing consistency becomes even more critical than for those with conventional schedules.

- —

When Inflammation Overwhelms the Brain’s Cleanup Crews

Neuroinflammation initially evolved as a protective response, with microglial cells engulfing debris and releasing signals that recruit additional cleanup resources. In Alzheimer’s disease, this system turns destructive through a process called inflammaging””chronic, low-grade inflammatory activation that damages tissue while failing to clear the proteins that triggered it. Activated microglia cluster around amyloid plaques but become progressively dysfunctional, releasing inflammatory cytokines that kill nearby neurons while losing their ability to actually phagocytose and digest the aggregates. The warning here concerns well-intentioned anti-inflammatory interventions that may backfire at certain disease stages. Clinical trials of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in established Alzheimer’s disease showed no benefit and possible harm, despite epidemiological studies suggesting that long-term NSAID users had lower dementia risk.

The explanation may involve timing: suppressing inflammation before significant pathology develops might preserve microglial function, while suppressing it after microglia have already become dysfunctional removes what little cleanup capacity remains. This limitation extends to newer experimental anti-inflammatory approaches. Drugs targeting specific inflammatory pathways show promise in animal models when given early, but translation to human trials has been complicated by difficulty identifying patients at the optimal intervention window. By the time symptoms prompt medical attention and diagnosis, inflammatory damage may have progressed beyond the point where suppression alone can restore function. Current research focuses on combination approaches that reduce harmful inflammation while simultaneously enhancing alternative clearance pathways.

- —

The Emerging Role of Peripheral Organs in Brain Protein Clearance

Recent research has expanded understanding of protein clearance beyond the brain itself, revealing that peripheral organs””particularly the liver””play significant roles in eliminating amyloid-beta that reaches the bloodstream. This discovery emerged from an elegant experiment: researchers connected the circulatory systems of young and old mice, finding that old mice with access to young blood showed reduced brain amyloid, while young mice connected to old partners accumulated more. The young liver’s superior ability to filter amyloid from blood affected brain levels in the connected partner. This finding suggests that systemic health directly impacts brain clearance capacity.

Individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease show elevated blood amyloid-beta levels and increased Alzheimer’s risk, independent of other factors. Similarly, kidney function correlates with amyloid clearance, as these organs filter and eliminate waste products including proteins transported out of the brain. The practical example here involves patients with chronic kidney disease, who show accelerated cognitive decline potentially linked to impaired peripheral clearance. These connections reinforce why cardiovascular and metabolic health matter for brain health””they maintain the organs responsible for final elimination of proteins the brain manages to clear.

- —

How to Prepare

- **Assess your sleep architecture objectively.** Consider a sleep study or use a validated wearable device that measures sleep stages, not just duration. Identify whether you’re achieving adequate deep sleep or primarily cycling through lighter stages.

- **Evaluate cardiovascular and metabolic markers.** Request blood pressure trends, fasting glucose, lipid panels, and inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein. These indicate the health of systems supporting protein clearance beyond the brain itself.

- **Review medications for sleep-disrupting effects.** Many common medications””beta-blockers, certain antidepressants, antihistamines, and decongestants””alter sleep architecture. Discuss alternatives with your physician if deep sleep appears compromised.

- **Document your current sleep environment and habits.** Note room temperature, light exposure, evening routines, and timing consistency. These factors directly influence slow-wave sleep quantity.

- **Understand your genetic risk context.** If you carry APOE4 or have family history of Alzheimer’s, clearance optimization becomes more urgent and may justify more aggressive interventions.

How to Apply This

- **Prioritize sleep timing consistency over duration flexibility.** Maintain the same sleep and wake times within a 30-minute window, even on weekends. This synchronizes glymphatic function with circadian peaks in clearance activity.

- **Implement strategic exercise timing.** Moderate aerobic exercise, completed at least 4-6 hours before bedtime, enhances deep sleep and has been shown to increase glymphatic flow. Exercise too close to sleep, however, can impair sleep quality through elevated body temperature and cortisol.

- **Address obstructive sleep apnea aggressively.** Untreated sleep apnea dramatically reduces deep sleep and creates intermittent oxygen deprivation that damages clearance mechanisms. Treatment with CPAP or oral appliances can restore more normal clearance function.

- **Consider sleep position.** Preliminary research suggests lateral (side) sleeping may enhance glymphatic drainage compared to supine or prone positions. While evidence remains early, this zero-cost modification carries no downside.

Expert Tips

- **Don’t assume more sleep is always better.** Excessive sleep duration (more than 9 hours regularly) is associated with increased dementia risk in epidemiological studies, possibly reflecting underlying disease rather than causing harm, but the relationship suggests diminishing returns beyond adequate duration.

- **Recognize that alcohol’s sedative effect is not sleep.** Alcohol initially induces unconsciousness but severely suppresses deep sleep during the second half of the night, precisely when glymphatic clearance should peak.

- **Understand that intense late-night mental activity may impair clearance.** Engaging in highly stimulating cognitive work before bed keeps certain brain regions active and may reduce the synchronized slow-wave activity necessary for optimal fluid flow.

- **Don’t overlook nasal breathing.** Nasal obstruction and chronic mouth breathing are associated with worse sleep quality and potentially reduced clearance. Address allergies, deviated septums, or other obstruction sources.

- **Consider that clearance optimization applies to caregivers too.** Those caring for dementia patients often suffer severe sleep disruption, placing them at elevated risk. Respite care and shared caregiving responsibilities aren’t luxuries””they’re protective interventions.

- —

Conclusion

Protein clearance failure in Alzheimer’s disease results from the convergence of multiple impaired systems””glymphatic drainage compromised by poor sleep and vascular stiffness, cellular autophagy declining with age, blood-brain barrier breakdown reducing transvascular transport, and inflammatory responses that damage rather than repair. Understanding these interconnected mechanisms explains why single-target pharmaceutical approaches have largely failed and why multi-domain interventions addressing sleep, cardiovascular health, and metabolic function show more promise in prevention trials. The practical implications are both sobering and empowering.

Clearance capacity declines begin decades before symptoms appear, meaning protective measures ideally start in midlife or earlier. Yet even later interventions can slow progression by preserving remaining clearance function. The emphasis on sleep quality, not merely duration, provides an accessible target for immediate action. As research continues into pharmacological methods of enhancing specific clearance pathways, lifestyle interventions remain the evidence-based foundation for supporting your brain’s ability to maintain protein homeostasis throughout life.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it typically take to see results?

Results vary depending on individual circumstances, but most people begin to see meaningful progress within 4-8 weeks of consistent effort. Patience and persistence are key factors in achieving lasting outcomes.

Is this approach suitable for beginners?

Yes, this approach works well for beginners when implemented gradually. Starting with the fundamentals and building up over time leads to better long-term results than trying to do everything at once.

What are the most common mistakes to avoid?

The most common mistakes include rushing the process, skipping foundational steps, and failing to track progress. Taking a methodical approach and learning from both successes and setbacks leads to better outcomes.

How can I measure my progress effectively?

Set specific, measurable goals at the outset and track relevant metrics regularly. Keep a journal or log to document your journey, and periodically review your progress against your initial objectives.

When should I seek professional help?

Consider consulting a professional if you encounter persistent challenges, need specialized expertise, or want to accelerate your progress. Professional guidance can provide valuable insights and help you avoid costly mistakes.

What resources do you recommend for further learning?

Look for reputable sources in the field, including industry publications, expert blogs, and educational courses. Joining communities of practitioners can also provide valuable peer support and knowledge sharing.