Older adults lose muscle mass primarily because of age-related hormonal decline, cellular dysfunction, and cumulative inactivity — a condition called sarcopenia. The process begins earlier than most people expect. Starting around age 30, the body loses roughly 3 to 5 percent of muscle mass per decade, and after 60, that rate accelerates noticeably. The good news is that sarcopenia is not inevitable in its severity.

Resistance training, adequate protein intake, and early screening can meaningfully slow or partially reverse the trajectory. Consider a 68-year-old woman who notices she’s struggling to carry groceries she handled easily a decade ago. That decline isn’t simply “getting older” in some vague sense — it reflects measurable losses in muscle fiber size and number, compounded by hormonal shifts following menopause, and likely some degree of reduced physical activity over the years. This article covers the biological mechanisms driving muscle loss, the hormonal changes specific to men and women, the molecular processes involved, and — critically — what the current evidence says about exercise, nutrition, and when to start screening.

Table of Contents

- What Is Sarcopenia and How Common Is Age-Related Muscle Loss?

- What Hormonal Changes Drive Muscle Loss in Aging Men and Women?

- What Is Happening Inside the Muscle Cells Themselves?

- What Lifestyle Factors Accelerate Muscle Loss — and What Slows It?

- What Does the Research Actually Say About Exercise as a Preventive Strategy?

- The Role of Nutrition Beyond Protein — Omega-3s and Dietary Patterns

- When Should Screening Begin — and What Does That Look Like?

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Sarcopenia and How Common Is Age-Related Muscle Loss?

Sarcopenia is the clinical term for the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength that accompanies aging. It’s more than a cosmetic concern. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, supports balance and mobility, and has direct ties to cognitive health — loss of it contributes to falls, fractures, loss of independence, and a growing body of research links poor muscle function to increased dementia risk. Estimates suggest that between 10 and 20 percent of older adults have sarcopenia. Among adults aged 40 to 64, roughly 8.85 percent are affected. That figure nearly doubles — reaching about 15.51 percent — in adults 65 and older, according to data from the Cleveland Clinic.

These aren’t fringe cases. In a room of twenty older adults at a senior center, statistically two or three of them meet clinical criteria for the condition. The condition often goes undiagnosed for years because muscle loss is gradual and easily attributed to normal aging. There’s no pain signal, no obvious acute event. People adapt — taking the elevator instead of stairs, sitting more, reaching for lighter items. By the time significant functional impairment is noticeable, substantial loss may already have occurred.

What Hormonal Changes Drive Muscle Loss in Aging Men and Women?

Hormones play a central role in maintaining muscle mass throughout adulthood, and their decline with age directly disrupts that maintenance. In men, testosterone levels fall with age, and approximately 60 percent of men over 65 experience a degree of andropause — the gradual reduction in testosterone that blunts muscle protein synthesis and reduces the anabolic stimulus muscle tissue depends on. Growth hormone and IGF-1, which promote muscle repair and growth, also decline with age in both sexes. For women, the hormonal picture shifts sharply at menopause. Estrogen decline doesn’t just affect bone density; it accelerates both muscle mass loss and strength reduction.

Research published in PMC confirms that estrogen plays an active role in maintaining musculoskeletal function, and its withdrawal at menopause represents a meaningful physiological turning point. Vitamin D, which supports muscle fiber function and is frequently deficient in older adults, also declines with age and contributes further to the problem. It’s worth noting a limitation here: hormone replacement therapy has been studied as a potential intervention, but the evidence for its use specifically to preserve muscle mass remains mixed and complicated by cardiovascular and oncological risk considerations. The hormonal causes of sarcopenia are real and measurable, but they don’t straightforwardly translate into a simple hormonal fix. Lifestyle interventions remain the primary evidence-backed response.

What Is Happening Inside the Muscle Cells Themselves?

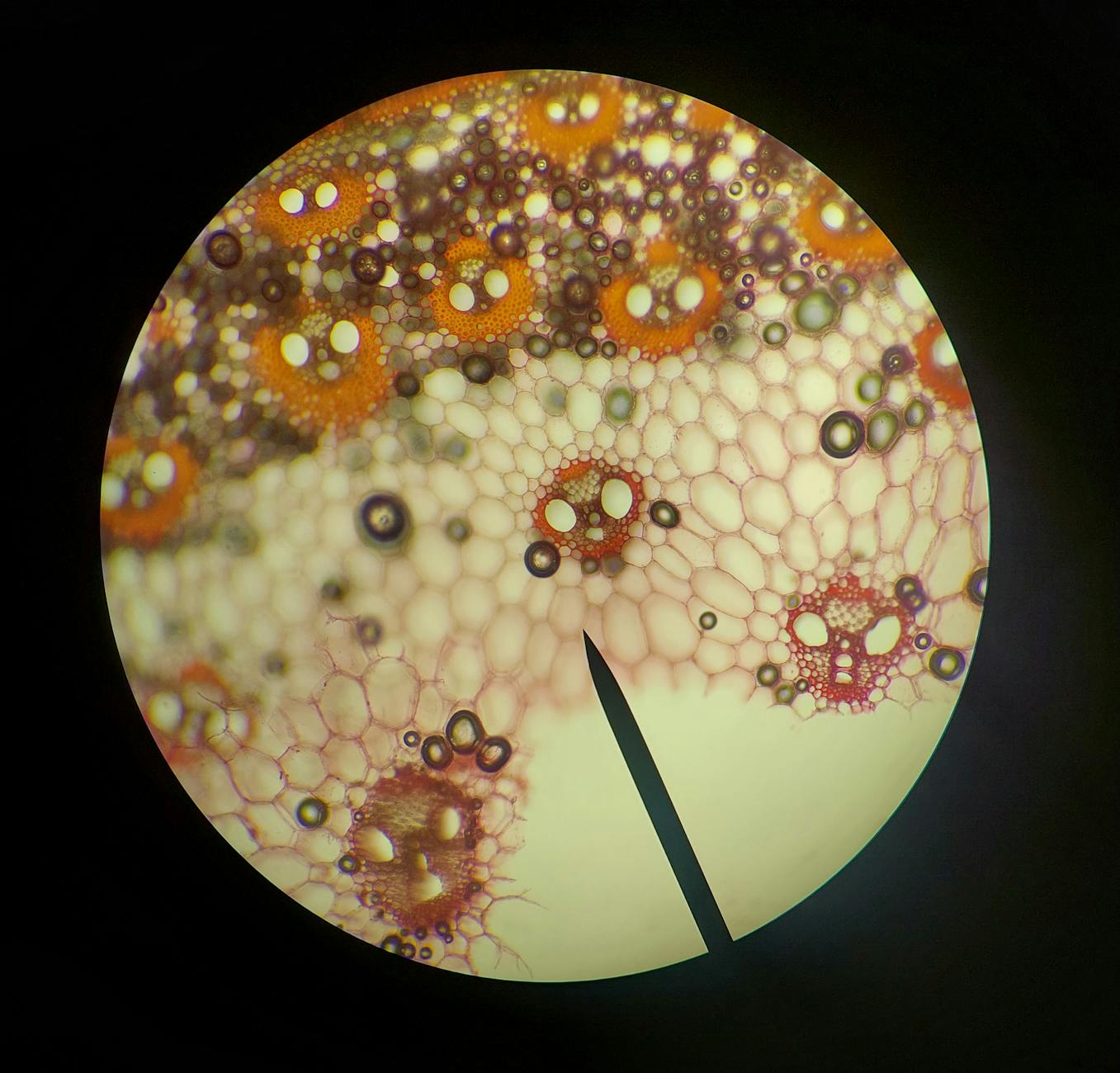

Beyond hormones, sarcopenia has deep molecular roots that researchers are still working to fully characterize. At the cellular level, several processes go wrong simultaneously. Satellite cells — the stem cells responsible for repairing and regenerating muscle fibers — lose their functional capacity with age. When muscle tissue is damaged through normal use, these cells are supposed to activate, proliferate, and rebuild. In older adults, that response is blunted. Mitochondrial dysfunction compounds the problem.

Mitochondria in muscle cells become less efficient and more prone to dysfunction with age, reducing the energy available for muscle contraction and repair. Meanwhile, chronic low-grade inflammation — sometimes called “inflammaging” — creates a systemic environment that is hostile to muscle maintenance. Unlike the acute inflammation that follows an injury, inflammaging is persistent and low-level, and it gradually degrades protein homeostasis in muscle tissue. Myonuclear disorganization, another age-related cellular change, further disrupts the coordination needed for healthy muscle protein turnover. A 2025 review in Frontiers in Aging identified these molecular constraints as key targets for future therapeutic development. Understanding them is important not just for researchers but for clinicians and caregivers: they explain why sarcopenia isn’t simply reversed by “trying harder” or eating a bit more protein. The cellular machinery itself is compromised, which is why comprehensive, consistent intervention — rather than sporadic effort — is what the evidence supports.

What Lifestyle Factors Accelerate Muscle Loss — and What Slows It?

Physical inactivity is the most modifiable contributor to sarcopenia. Muscle tissue follows a use-it-or-lose-it principle in a fairly literal sense. Extended periods of bed rest or sedentary living accelerate atrophy dramatically — studies of hospitalized older adults consistently show significant muscle loss even over short stays. Conversely, staying physically active across the lifespan is one of the strongest protective factors. Poor protein intake is the second major lifestyle driver. Many older adults eat less overall as appetite decreases with age, and protein intake often falls disproportionately.

Current evidence, including a 2025 PMC review of nutrition and exercise for sarcopenia, recommends a minimum of 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for managing sarcopenia — notably higher than the general adult recommendation of 0.8 g/kg/day. For a 70 kg (154 lb) person, that means at least 84 grams of protein daily, which requires deliberate planning. Spreading protein across meals rather than concentrating it in one sitting appears to support muscle protein synthesis more effectively. Chronic illness adds another layer. Conditions like type 2 diabetes, heart failure, COPD, and cancer all independently accelerate muscle loss, and many older adults are managing multiple such conditions simultaneously. This creates a compounding effect that makes the case for early intervention even stronger — waiting until function is already significantly impaired leaves fewer tools available and a harder baseline to work from.

What Does the Research Actually Say About Exercise as a Preventive Strategy?

Resistance training — lifting weights, using resistance bands, performing bodyweight exercises that challenge the muscles against load — is the only intervention with strong, consistent evidence for slowing sarcopenia’s progression. This isn’t a contested point in the literature. Aerobic exercise is beneficial for cardiovascular health and has some muscle-preserving effects, but it does not produce the same anabolic stimulus for muscle maintenance that resistance work does. The 2025 expert consensus published in Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences adds important nuance: multimodal exercise programs — those combining resistance training with aerobic exercise and balance training — outperform single-mode programs.

Balance training matters particularly because the goal isn’t just preserving muscle mass in isolation; it’s preserving functional capacity and fall prevention. An older adult who gains some muscle strength through resistance training but still has poor proprioception and coordination remains at elevated fall risk. A key warning here: not all resistance training programs are equal for this population, and poorly designed programs can cause injury. The intensity needs to be sufficient to create an adaptive stimulus — light exercise that never challenges the muscle beyond its comfort zone produces minimal results — but load progression must be gradual and supervised, particularly for adults who are deconditioned or managing joint conditions like osteoarthritis. Starting a resistance training program at 70 or 75 is absolutely beneficial and not too late, but it warrants guidance from a physical therapist or certified trainer experienced with older adults.

The Role of Nutrition Beyond Protein — Omega-3s and Dietary Patterns

Protein gets the most attention in sarcopenia nutrition discussions, but it isn’t the only dietary factor that matters. A 2025 PMC study found that omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) at doses above 2.5 grams per day showed the most significant improvement in upper limb strength and lower limb function compared to placebo — a meaningful finding that suggests fish oil supplementation at therapeutic doses may be a useful adjunct to resistance training, not just a general wellness recommendation.

A Mediterranean-style diet — emphasizing vegetables, fruits, lean protein, legumes, and olive oil — is associated with better muscle function in older adults. This pattern happens to be high in anti-inflammatory compounds, which aligns with what we know about inflammaging as a driver of sarcopenia. For a person managing both muscle loss and cognitive decline risk, this dietary approach has overlapping benefits: the same foods that support muscle maintenance also support vascular and brain health.

When Should Screening Begin — and What Does That Look Like?

For years, clinical guidelines focused sarcopenia screening on adults 65 and older. The Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia’s 2025 consensus update changed that, recommending that assessment begin at age 50. The reasoning is straightforward: by the time functional decline is obvious in a 70-year-old, significant loss has already accumulated. Earlier identification allows earlier intervention.

The primary assessment tools are grip strength and walking speed — both simple, low-cost, and reliable indicators of overall muscle function. A handgrip dynamometer test takes seconds and provides clinically meaningful data. These tools can be used in primary care settings without specialized equipment. For clinicians and families thinking about dementia prevention alongside muscle health, this expanded screening window represents an opportunity: catching sarcopenia early keeps more preventive options on the table, and maintaining physical function in midlife has downstream benefits for cognitive resilience as well.

Conclusion

Sarcopenia is a gradual, biologically driven process rooted in hormonal decline, cellular dysfunction, and lifestyle factors — but it is neither inevitable in its severity nor untreatable. The research is clear that resistance training is the cornerstone intervention, ideally combined with aerobic and balance work, and that protein intake needs to be deliberately adequate rather than assumed.

The emerging picture from 2025 research adds omega-3 supplementation and earlier screening as meaningful tools in the prevention toolkit. For anyone involved in the care of an older adult — or planning ahead for their own aging — the practical takeaways are concrete: start resistance training and keep it consistent, aim for 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight daily, consider a Mediterranean dietary pattern, discuss sarcopenia screening at 50 rather than waiting for visible decline, and treat muscle preservation as a component of brain health, not a separate concern. The muscles and the mind age together, and the interventions that protect one tend to support the other.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age does muscle loss typically begin?

Muscle loss begins around age 30, with adults losing roughly 3 to 5 percent of muscle mass per decade. The rate accelerates significantly after age 60. This makes midlife an important window for building and maintaining muscle before the steeper decline begins.

Is sarcopenia the same as just feeling weak as you age?

Not exactly. Sarcopenia is a specific clinical condition defined by measurable loss of muscle mass combined with reduced strength or physical performance. General age-related weakness may overlap with it, but sarcopenia has specific diagnostic thresholds measured through grip strength testing, walking speed, and muscle mass assessment.

Can you reverse sarcopenia once it has started?

Partial reversal is possible. Consistent resistance training and adequate protein intake have both been shown to increase muscle mass and strength even in older adults with existing sarcopenia. Full reversal is unlikely, but meaningful functional improvement — reduced fall risk, better mobility, improved quality of life — is achievable with sustained effort.

How much protein do older adults actually need?

Current evidence supports a minimum of 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for adults managing sarcopenia — higher than the general adult recommendation of 0.8 g/kg/day. For a 70 kg person, that’s at least 84 grams daily, ideally distributed across meals rather than consumed mostly at one sitting.

Does walking count as sufficient exercise to prevent sarcopenia?

Walking is beneficial for cardiovascular health and general mobility, but it does not provide adequate resistance stimulus to meaningfully slow sarcopenia. Resistance training — exercises that challenge muscles against load — is required. Walking can be a valuable component of a multimodal program but should not be the sole exercise strategy for muscle preservation.

Is there a connection between muscle loss and dementia risk?

Research increasingly suggests a bidirectional relationship between muscle health and cognitive function. Poor grip strength and low muscle mass are associated with elevated dementia risk, and conditions that accelerate sarcopenia — physical inactivity, poor nutrition, chronic inflammation — also impair brain health. Maintaining muscle function appears to be part of a broader strategy for cognitive resilience.