Bone injuries pose exceptional dangers for Parkinson’s patients because the disease creates a perfect storm of risk factors that turn what might be a recoverable setback for others into a potentially life-altering or fatal event. The combination of impaired mobility, medication side effects, and compromised bone density means that a simple fall resulting in a hip fracture can trigger a cascade of complications””immobility leading to pneumonia, blood clots, rapid cognitive decline, and loss of independence. Studies show that hip fractures in Parkinson’s patients carry a mortality rate nearly double that of the general elderly population, with approximately 20-30% dying within one year of the injury. Consider a 72-year-old man with moderate Parkinson’s disease who trips on a rug and fractures his hip.

For someone without Parkinson’s, surgery and rehabilitation might return them to baseline function within a few months. For this patient, the enforced bed rest accelerates muscle wasting, his tremors worsen without regular movement, anesthesia from surgery may trigger prolonged confusion or delirium, and the pain medications can interact dangerously with his dopaminergic drugs. What follows is often a sharp, permanent decline in both physical and cognitive function. This article examines why Parkinson’s patients face heightened bone injury risks, how the disease itself weakens bones, the specific challenges of surgical recovery, strategies for prevention, and what caregivers should know about protecting their loved ones from this underappreciated threat.

Table of Contents

- What Makes Bone Injuries Especially Dangerous in Parkinson’s Disease?

- How Parkinson’s Disease Weakens Bones Over Time

- The Heightened Fall Risk in Parkinson’s Patients

- Practical Steps to Prevent Bone Injuries in Parkinson’s Patients

- Complications of Bone Injury Recovery in Parkinson’s Patients

- The Role of Nutrition and Bone Health Screening

- Looking Ahead: Emerging Approaches to Bone Protection

- Conclusion

What Makes Bone Injuries Especially Dangerous in Parkinson’s Disease?

The danger of bone injuries in Parkinson’s patients stems from a complex interplay between the disease‘s motor symptoms, its effects on bone metabolism, and the profound vulnerability that immobilization creates. Parkinson’s disease fundamentally disrupts the body’s ability to maintain balance, react to stumbles, and protect itself during falls. Unlike healthy individuals who instinctively extend their arms or shift their weight to break a fall, Parkinson’s patients often experience “freezing” episodes or delayed reflexes that leave them falling directly onto vulnerable bones like the hip, wrist, or spine. The aftermath of a bone injury is where the real danger multiplies. Parkinson’s patients rely heavily on continuous movement to manage their symptoms””walking helps maintain mobility, reduces stiffness, and supports the effectiveness of their medications.

When a fracture forces immobilization, symptoms typically worsen dramatically. A patient who could walk independently before a hip fracture may never regain that ability, not because the bone didn’t heal, but because the weeks of immobility caused irreversible decline in muscle strength, coordination, and medication response. Comparing outcomes illustrates the disparity clearly. A 2019 study in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research found that Parkinson’s patients experienced surgical complications at rates 50% higher than matched controls, longer hospital stays averaging 2-3 additional days, and significantly higher rates of discharge to nursing facilities rather than home. The fracture itself is often just the beginning of a much larger medical crisis.

How Parkinson’s Disease Weakens Bones Over Time

parkinson‘s disease contributes to bone loss through multiple mechanisms that often go unrecognized until a fracture occurs. Reduced physical activity is the most obvious factor””as the disease progresses and movement becomes more difficult, patients naturally become more sedentary. Bones require mechanical stress to maintain density, and the decreased walking, standing, and weight-bearing activity leads to accelerated osteoporosis. Research indicates that Parkinson’s patients have bone mineral density scores 10-15% lower than age-matched peers without the disease. However, the connection runs deeper than simple disuse. Parkinson’s patients frequently have lower vitamin D levels, partly because they spend less time outdoors and partly because the disease may affect vitamin D metabolism directly.

Levodopa, the gold-standard medication for Parkinson’s, has been associated with elevated homocysteine levels, which in turn correlate with reduced bone density. Some studies suggest that the dopamine deficiency itself may affect bone remodeling, though this research remains preliminary. One important limitation to understand: not all Parkinson’s patients face equal bone loss risk. Those diagnosed at younger ages, those who remain physically active, and those who receive bone density screening and appropriate treatment may maintain relatively healthy bones for years. The danger lies in assuming that bone health is an inevitable casualty of the disease rather than a modifiable risk factor. Patients who begin bone-protective strategies early””including vitamin D supplementation, weight-bearing exercise within their capabilities, and bone density monitoring””can significantly reduce their fracture risk.

The Heightened Fall Risk in Parkinson’s Patients

Falls represent the primary mechanism by which Parkinson’s patients sustain bone injuries, and the disease creates fall risk through nearly every one of its symptoms. Bradykinesia””the slowness of movement characteristic of Parkinson’s””means patients cannot react quickly enough when they begin to lose balance. Rigidity reduces the flexibility needed to catch oneself. Postural instability, which worsens as the disease progresses, means patients have difficulty maintaining their center of gravity even while standing still. The phenomenon of freezing of gait deserves particular attention. During a freezing episode, a patient’s feet seem glued to the floor despite their intention to move. When freezing breaks suddenly, the forward momentum they were generating can propel them into a fall.

These episodes often occur at thresholds, doorways, or when initiating walking””precisely the moments when environmental hazards may be present. A patient freezing at the top of a staircase faces obvious catastrophic risk. Consider a specific example: a woman with Parkinson’s disease of eight years gets up at night to use the bathroom. Her dopaminergic medication has worn off during sleep, worsening her symptoms. The bedroom is dark, she’s disoriented from sleep, and when she stands, orthostatic hypotension””another common Parkinson’s feature””causes her blood pressure to drop suddenly. She feels dizzy, freezes mid-step, and falls forward onto her outstretched wrist, sustaining a Colles fracture. This scenario, or variations of it, plays out thousands of times yearly in Parkinson’s patients.

Practical Steps to Prevent Bone Injuries in Parkinson’s Patients

Prevention requires addressing both bone strength and fall risk simultaneously, and families must weigh the tradeoffs involved in various protective strategies. Home modification represents the first line of defense: removing throw rugs, installing grab bars in bathrooms, ensuring adequate lighting throughout living spaces, and considering motion-activated night lights for nighttime navigation. These changes can reduce fall risk by 20-40% according to home safety research, though they require upfront investment and may change the aesthetic of a family home. Physical therapy specifically designed for Parkinson’s patients offers significant benefits but demands consistent commitment. Programs like LSVT BIG focus on exaggerated movements that help overcome bradykinesia, while balance-focused exercises can improve postural stability.

The tradeoff here involves time, cost, and the need for ongoing participation””benefits fade within weeks if exercise stops. Some patients and families find that group exercise classes designed for Parkinson’s patients provide both physical benefits and valuable social support, making adherence easier. Medication timing represents an often-overlooked prevention opportunity. Working with a neurologist to optimize “on” time””when medications are working effectively””during high-risk periods like morning rising and nighttime bathroom trips can substantially reduce fall risk. However, this requires careful tracking of symptom patterns and may involve complex medication adjustments. Some patients benefit from wearing a hip protector, essentially padded underwear that cushions falls, though compliance is often poor because the garments can be uncomfortable and inconvenient.

Complications of Bone Injury Recovery in Parkinson’s Patients

The recovery period following a bone injury presents unique challenges that can derail even initially successful treatment. Anesthesia and surgery carry heightened risks for Parkinson’s patients””general anesthesia can trigger prolonged confusion, hallucinations, or delirium that may persist for weeks. Some anesthetic agents and pain medications interact with Parkinson’s drugs or worsen symptoms. Surgeons and anesthesiologists unfamiliar with Parkinson’s disease may inadvertently discontinue dopaminergic medications during the perioperative period, leading to dangerous symptom flares. Rehabilitation after fracture surgery demands careful attention to medication timing and symptom management. Physical therapists working with Parkinson’s patients must understand that functional ability fluctuates throughout the day as medications cycle on and off.

Scheduling therapy sessions during “on” times maximizes progress, while attempting rehabilitation during “off” periods may be futile or even dangerous. Pain from the injury itself complicates matters further””adequate pain control is essential for rehabilitation participation, but many pain medications cause sedation, confusion, or constipation that compound Parkinson’s challenges. A critical warning: delirium following surgery is not benign in Parkinson’s patients. While post-operative confusion often resolves within days in otherwise healthy elderly patients, it frequently marks a turning point in Parkinson’s disease progression. Studies have documented permanent cognitive decline following surgical delirium in this population, with some patients developing dementia that was not previously apparent. Families should advocate strongly for delirium prevention strategies, including maintaining sleep-wake cycles, keeping familiar objects present, ensuring hearing aids and glasses are available, and minimizing unnecessary medications.

The Role of Nutrition and Bone Health Screening

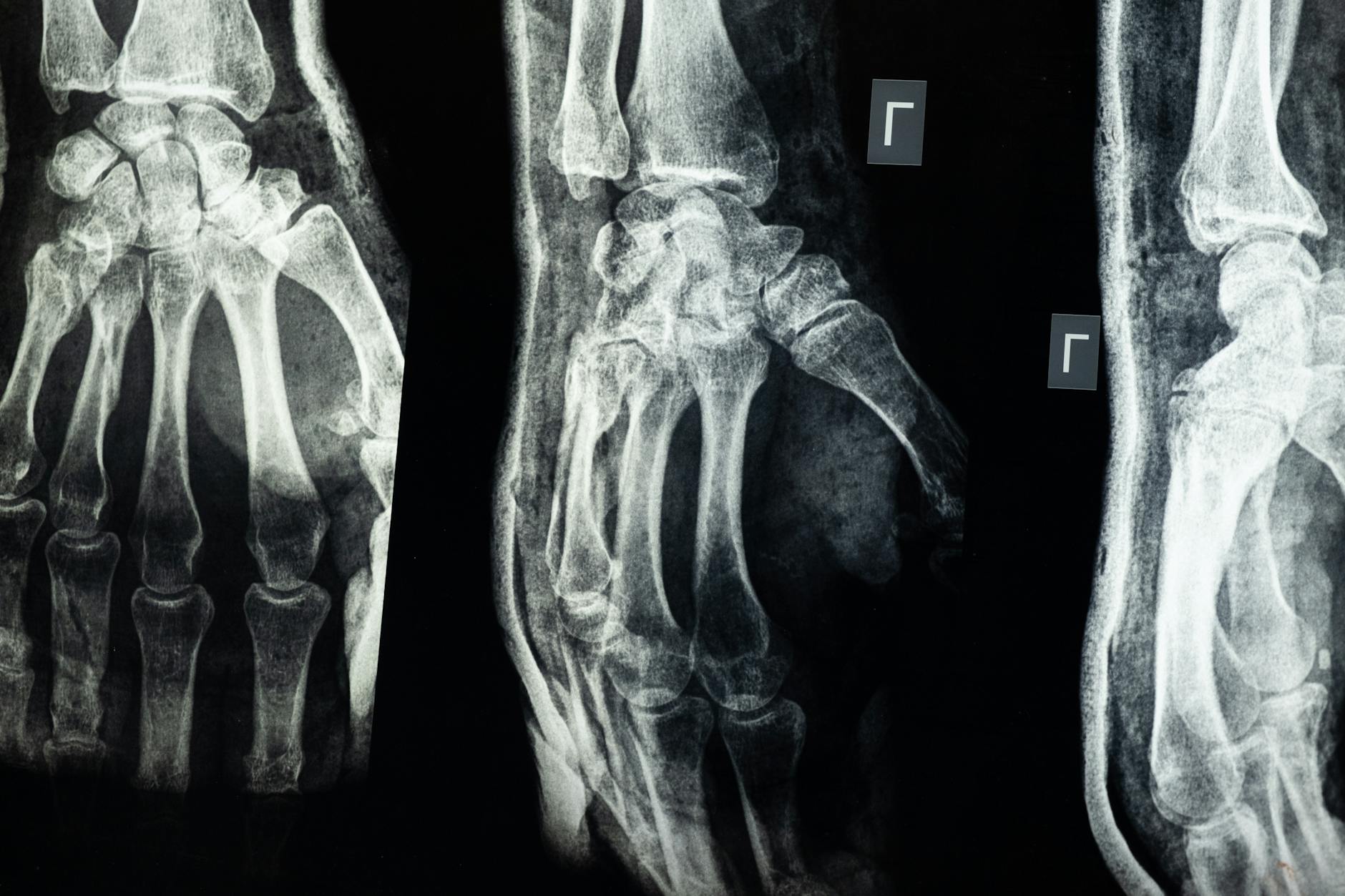

Proactive bone health management can reduce fracture risk before a fall ever occurs, yet many Parkinson’s patients never receive bone density testing. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning can identify osteoporosis or its precursor, osteopenia, allowing for treatment that strengthens bones before they break. Medical guidelines increasingly recommend routine bone density screening for Parkinson’s patients, particularly those over 65, those taking medications associated with bone loss, or those with prior fractures.

A practical example illustrates the value of screening: a 68-year-old woman diagnosed with Parkinson’s three years ago undergoes DEXA scanning that reveals significant osteoporosis in her hip and spine. Her physician prescribes a bisphosphonate medication that, over several years, increases her bone density by 5-8%. When she eventually does fall two years later, her strengthened bones sustain a bruise rather than a fracture””an outcome that likely preserves her independence and possibly her life. Without screening, she would have remained unaware of her brittle bones until they broke.

Looking Ahead: Emerging Approaches to Bone Protection

Research continues to explore better ways to protect Parkinson’s patients from bone injuries, with several promising directions emerging. Wearable technology that detects freezing episodes before they cause falls is under development, potentially alerting patients or caregivers in time to prevent injury. Some researchers are investigating whether certain Parkinson’s medications might have bone-protective effects, which could influence prescribing decisions.

Exercise programs delivered through virtual reality show promise for improving both adherence and outcomes, making consistent physical activity more engaging and accessible for patients with limited mobility. The growing recognition of bone health as a critical component of Parkinson’s care represents perhaps the most important shift. As more neurologists incorporate bone density screening and fall risk assessment into routine care, and as more orthopedic surgeons develop expertise in managing Parkinson’s patients after fractures, outcomes should improve. For now, patients and families must often advocate for this comprehensive approach themselves, but the trajectory of care is moving in a hopeful direction.

Conclusion

Bone injuries represent one of the most serious yet preventable complications of Parkinson’s disease. The combination of increased fall risk, accelerated bone loss, and difficult recovery creates a situation where a single fracture can permanently alter a patient’s quality of life and independence. Understanding these interconnected risks empowers patients, families, and caregivers to take meaningful preventive action.

The most important steps involve addressing both sides of the equation simultaneously: strengthening bones through nutrition, appropriate medication when indicated, and weight-bearing exercise; while reducing fall risk through home modifications, physical therapy, and careful medication timing. Early bone density screening identifies those at highest risk before a fracture occurs. When fractures do happen, working with medical teams experienced in Parkinson’s care can improve outcomes and reduce the risk of permanent decline. Vigilance and prevention remain the most powerful tools available.