When a doctor suspects dementia, one of the first questions families ask is whether their loved one needs an MRI or a CT scan — and whether one is better than the other. The short answer is that MRI is generally the preferred imaging tool for evaluating dementia because it offers superior detail, particularly in detecting early brain changes like hippocampal shrinkage and small vessel disease. CT scans, by contrast, are typically used to rule out other conditions — tumors, bleeds, or fluid buildup — that can mimic dementia symptoms. Both scans produce images of the brain, but they work through entirely different technologies and are suited to different clinical questions. Consider a 74-year-old presenting with progressive memory loss over 18 months.

Her neurologist orders an MRI first. It reveals subtle atrophy in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex — regions critical to memory — along with small areas of white matter change consistent with early vascular damage. A CT scan in the same patient might have shown gross brain shrinkage and ruled out a brain tumor, but it likely would have missed those smaller, diagnostically significant findings. That gap in sensitivity is why imaging choice matters. This article covers how each technology works, what each can and cannot detect, when CT is the better option, and why neither scan alone can confirm a dementia diagnosis.

Table of Contents

- How Do MRI and CT Scans Differ in the Way They Work?

- What Can Each Scan Actually Detect in Dementia Evaluation?

- Which Scan Is Better for Specific Types of Dementia?

- When Is a CT Scan the Better or Only Option?

- Why Neither Scan Can Diagnose Dementia on Its Own

- Advanced and Emerging Imaging Approaches

- What Families Should Expect from the Imaging Process

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Do MRI and CT Scans Differ in the Way They Work?

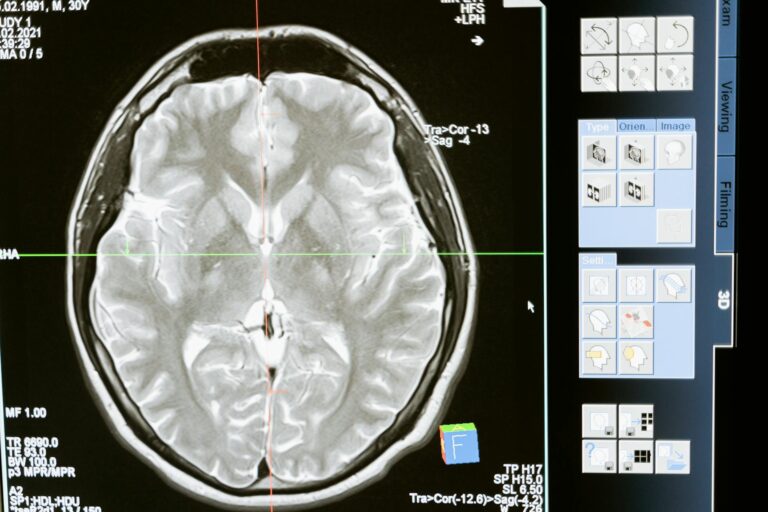

CT scans — computed tomography — use X-ray radiation directed through the skull at multiple angles, which a computer then assembles into cross-sectional images of the brain. The process is fast, typically completed in a few minutes, and the equipment is widely available in most hospitals and imaging centers. The tradeoff is radiation exposure and relatively lower soft-tissue contrast compared to MRI. MRI — magnetic resonance imaging — works through an entirely different mechanism.

It uses powerful magnetic fields and radio waves to detect the behavior of hydrogen atoms in body tissue, producing images without any ionizing radiation. Because brain tissue is rich in water, MRI generates exceptional contrast between gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. For dementia workups, this contrast matters enormously: it allows radiologists to see structural details that a CT scan would not clearly resolve, including subtle atrophy in specific brain regions, small strokes, and early changes to white matter tracts. The price of that detail is time — a brain mri typically takes 30 to 60 minutes — and higher cost.

What Can Each Scan Actually Detect in Dementia Evaluation?

Both MRI and CT can identify broad categories of brain pathology relevant to dementia: overall brain atrophy, large strokes, tumors, blood clots, infections, and fluid accumulation. For ruling out a structural cause of cognitive decline — say, a subdural hematoma or a brain tumor pressing on frontal lobe tissue — either scan can accomplish the task adequately. This is the primary role CT plays in dementia workups: fast, accessible exclusion of treatable conditions before a neurodegenerative process is considered. Where they diverge is sensitivity for the more nuanced changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. MRI can detect subtle hippocampal and entorhinal cortex atrophy — among the earliest structural markers of Alzheimer’s pathology.

It can also identify small infarcts (ministrokes), blood flow abnormalities, inflammation, and white matter hyperintensities that indicate small vessel disease. CT, even a high-quality modern CT, does not match this level of detail in soft tissue. However, there is an important caveat: imaging findings must always be interpreted in clinical context. A scan showing moderate hippocampal atrophy is consistent with Alzheimer’s disease, but hippocampal shrinkage also occurs with normal aging, depression, chronic stress, and other conditions. No scan result should be read in isolation.

Which Scan Is Better for Specific Types of Dementia?

For Alzheimer’s disease, MRI is strongly preferred. The hippocampus and entorhinal cortex are among the first regions affected by Alzheimer’s pathology, and their progressive atrophy can be tracked over time on MRI with a degree of precision that CT cannot match. Neurologists use standardized visual rating scales — such as the Scheltens scale for medial temporal lobe atrophy — applied specifically to MRI findings. These tools help clinicians distinguish the pattern of atrophy seen in Alzheimer’s from that seen in other dementias like frontotemporal dementia, where frontal and temporal lobe changes predominate.

For vascular dementia, MRI is particularly valuable because of its superior detection of small vessel disease — the cumulative damage to tiny blood vessels throughout the white matter that drives much of the cognitive decline in this condition. CT can show large infarcts and significant white matter changes, but the small, scattered lesions characteristic of microvascular disease are frequently invisible on CT. A patient with a history of hypertension and stepwise cognitive decline might have a CT scan that looks broadly normal while an MRI reveals extensive periventricular white matter changes that explain the clinical picture. For Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementia, structural MRI remains a standard part of workup, though the findings can be subtle, particularly early in the disease. In these cases, functional imaging — PET scans, DaTscan for Lewy body — often adds more diagnostic information than structural imaging alone.

When Is a CT Scan the Better or Only Option?

MRI is not always feasible or appropriate. Patients with certain metal implants — pacemakers, older cochlear implants, some aneurysm clips, retained metal fragments or shrapnel — cannot safely enter an MRI scanner because of the powerful magnetic field. In these cases, CT becomes the default imaging tool, and it still provides meaningful clinical information even if it cannot match MRI’s soft-tissue resolution. CT also wins on speed and availability. In emergency settings — a patient brought to the emergency department in acute confusion — a CT scan can be completed in minutes and immediately rule out a hemorrhagic stroke, large tumor, or hydrocephalus.

MRI in that same context would take far longer and may not be available around the clock at all facilities. For the initial triage of acute neurological events, CT is often the first tool used regardless of what might eventually come next. Cost is another practical consideration. MRI costs more than CT, and insurance coverage varies. Some patients, particularly in systems with limited resources, may be triaged to CT first with MRI reserved for cases where CT findings are ambiguous or where a higher level of detail is clinically justified. This is a genuine tradeoff — not an ideal one from a diagnostic standpoint, but a real-world constraint that affects clinical pathways in many settings.

Why Neither Scan Can Diagnose Dementia on Its Own

This is perhaps the most important limitation to understand: a brain scan — whether MRI or CT — cannot by itself diagnose dementia. Imaging is one component of a broader diagnostic workup that includes a detailed clinical history, cognitive testing (such as the Montreal Cognitive Assessment or neuropsychological battery), laboratory tests to exclude metabolic and thyroid causes, and, in some cases, biomarker testing through PET imaging or cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Brain atrophy visible on a scan is consistent with dementia but is not specific to it. Some degree of brain volume loss occurs with normal aging.

Conversely, some individuals in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease may have scans that appear broadly normal — the molecular changes of amyloid plaque deposition and tau pathology begin years or decades before structural atrophy becomes visible on imaging. For these patients, advanced biomarker testing — amyloid PET, tau PET, or CSF analysis for amyloid and tau proteins — may identify Alzheimer’s pathology long before structural MRI or CT can. The warning here is practical: a normal scan should not reassure a family that dementia is absent, nor should a scan showing atrophy be delivered to a family as a dementia diagnosis. Imaging informs clinical judgment; it does not replace it.

Advanced and Emerging Imaging Approaches

Beyond standard structural MRI, more specialized MRI protocols are increasingly used in dementia research and, in some specialist centers, clinical practice. Functional MRI (fMRI) maps brain activity patterns rather than just structure. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) visualizes white matter tract integrity. These tools are not yet routine in standard dementia workups but are expanding the field’s understanding of how different dementias affect brain connectivity over time.

PET scanning represents a different category altogether — one that can detect molecular pathology rather than structural change. Amyloid PET and tau PET scans can identify the biological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease in living patients. A newly approved blood test for amyloid is beginning to shift diagnostic pathways as well. These developments mean the question of MRI versus CT, while still important, is becoming part of a broader and more nuanced diagnostic toolkit than it was even a decade ago.

What Families Should Expect from the Imaging Process

If a loved one is being evaluated for possible dementia, it helps to understand that imaging is typically one step in a multi-appointment process, not a single definitive test. A GP or family physician may order a CT scan first as a rapid screen; a neurologist or geriatric psychiatrist may subsequently order MRI for greater detail. In some cases, imaging findings will be clear and informative.

In others, the scan may be largely normal at an early stage of disease, and the diagnosis will rest primarily on the clinical picture and cognitive testing. The field is moving toward earlier, more precise diagnosis — not just to name a condition sooner, but because emerging treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, including recently approved anti-amyloid therapies, are most likely to be beneficial when started early. That shift makes the quality and sensitivity of diagnostic imaging more consequential than ever, and it is one reason clinicians continue to advocate for MRI as the preferred first-line brain imaging tool when it is accessible and safe for the patient.

Conclusion

MRI and CT scans both have a role in dementia diagnosis, but they are not interchangeable. MRI is the preferred imaging tool when the clinical question involves detecting early or subtle brain changes — hippocampal atrophy, small vessel disease, white matter abnormalities — because its superior soft-tissue contrast and freedom from radiation make it both more sensitive and safer for repeated use. CT is faster, more accessible, and appropriate when the immediate goal is to rule out acute or treatable conditions, or when MRI is contraindicated due to metal implants.

What neither scan can do is provide a diagnosis on its own. Dementia diagnosis remains a clinical process, combining imaging with cognitive assessment, laboratory evaluation, patient history, and sometimes advanced biomarker testing. Families navigating this process should understand that a scan is a tool — a useful one, but always one piece of a larger picture.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is an MRI always necessary to diagnose dementia?

Not always. A CT scan may be ordered first to rule out treatable causes, and in some cases the clinical diagnosis is supported primarily by cognitive testing and history. However, MRI is the preferred imaging tool when greater detail is needed, particularly for Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

Can a CT or MRI scan tell you what type of dementia someone has?

Imaging can suggest patterns consistent with specific dementia types — for example, hippocampal atrophy on MRI is associated with Alzheimer’s disease, while frontal lobe atrophy may suggest frontotemporal dementia. But imaging alone rarely provides a definitive diagnosis of dementia type. A full clinical workup is required.

How long does a brain MRI take compared to a CT scan?

A CT scan of the brain typically takes just a few minutes. A brain MRI takes significantly longer — generally 30 to 60 minutes — which can be challenging for patients who have difficulty lying still.

Can someone with a pacemaker have an MRI for dementia?

Traditional pacemakers are a contraindication for standard MRI due to the magnetic field. Some newer MRI-conditional pacemakers may be compatible under specific protocols. In patients where MRI is not safe, CT is used as the alternative imaging tool.

Does a normal brain scan mean a person does not have dementia?

Not necessarily. Early-stage dementia, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, can exist before structural changes are visible on MRI or CT. A normal scan reduces the likelihood of certain causes but does not rule out a neurodegenerative process. Clinical evaluation and cognitive testing remain essential.

What is the next step if the MRI or CT scan results are inconclusive?

If structural imaging does not provide clear answers, a neurologist may recommend additional testing including neuropsychological assessment, PET imaging for amyloid or glucose metabolism, or cerebrospinal fluid analysis for Alzheimer’s biomarkers.