Online dementia screening tests have significant limitations that make them unsuitable as diagnostic tools, despite their growing popularity as a first step for concerned individuals and families. The core problem is straightforward: these tests measure a narrow slice of cognitive function under conditions that bear little resemblance to a clinical evaluation. They cannot account for education level, language background, anxiety during testing, or dozens of other variables that influence performance. A person with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease may score within normal ranges on a brief online quiz, while someone who slept poorly or is dealing with depression may score in a way that suggests impairment when none exists clinically.

Consider a 68-year-old retired teacher who takes a free online memory test after noticing some word-finding difficulties. She scores poorly on a timed memory recall section, triggering significant anxiety. When she eventually sees a neurologist and undergoes formal neuropsychological testing, the evaluation reveals her cognition is entirely appropriate for her age — her performance on the online test was influenced by test anxiety and an unfamiliar interface, not memory decline. This kind of false alarm is common. This article covers why online screening tests fall short, what they actually measure, the risks of over-relying on them, and what a proper evaluation actually involves.

Table of Contents

- Why Can’t Online Dementia Screening Tests Provide an Accurate Diagnosis?

- What Do Online Dementia Tests Actually Measure — And What Do They Miss?

- How Does Test Environment Affect the Reliability of Online Cognitive Screening?

- What Is the Risk of a False Negative or False Positive From an Online Screening Test?

- Can Online Tests Be Used Responsibly, and What Are the Warning Signs of Misleading Tools?

- What Role Should Online Screening Play in the Path to a Dementia Evaluation?

- Where Is Online Cognitive Testing Headed, and Will It Improve?

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Why Can’t Online Dementia Screening Tests Provide an Accurate Diagnosis?

Online dementia screening tests are designed to flag potential concerns, not confirm or rule out a diagnosis. Most of these tools — whether they are adaptations of the Montreal cognitive Assessment (MoCA), the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), or proprietary digital quizzes — were originally developed for use by trained clinicians in structured environments. When stripped of that context and administered remotely without supervision, their accuracy drops substantially. A clinician administering the MoCA in person can observe whether a patient is rushing, seems confused by instructions, or misunderstood a question. An online platform captures only the answer, not the process.

The psychometric properties of these tools — their sensitivity and specificity — were established in controlled research settings with defined populations. Sensitivity refers to a test’s ability to correctly identify people who do have a condition; specificity refers to its ability to correctly identify those who do not. Even formal, clinician-administered tools like the MMSE have known limitations around education bias: individuals with lower levels of formal education consistently score lower regardless of their actual cognitive status. Online tests rarely adjust for this, which means they systematically misclassify certain populations. Research published in neurological journals has repeatedly shown that brief cognitive screeners, even in clinical settings, should never stand alone as diagnostic instruments.

What Do Online Dementia Tests Actually Measure — And What Do They Miss?

Most online dementia tests evaluate a limited set of cognitive domains: short-term memory recall, orientation to time and place, basic arithmetic, and sometimes visuospatial ability. These are important areas, but dementia — particularly in its early stages — can present primarily through executive function deficits, language processing changes, or behavioral shifts that a five-minute quiz cannot detect. Frontotemporal dementia, for example, often spares memory in its early course while profoundly affecting judgment, social behavior, and impulse control. Someone with early frontotemporal dementia might score perfectly on a standard online memory test. Online tests also miss the longitudinal dimension entirely.

A single snapshot of cognitive performance tells you very little without a baseline. A person who has always functioned at a high cognitive level might score in the average range on an online test while actually experiencing significant decline from their personal norm. Conversely, someone who has never performed well on timed tests may score below average without any underlying pathology. Formal neuropsychological evaluations compare performance across multiple domains and, when prior test results are available, track change over time. However, if someone has a known neurological condition such as a prior stroke or traumatic brain injury, even this comparative approach becomes more complex, requiring careful interpretation by a specialist.

How Does Test Environment Affect the Reliability of Online Cognitive Screening?

The environment in which a cognitive test is administered has a measurable impact on performance. Clinical cognitive assessments are conducted in quiet rooms, with a standardized protocol, consistent lighting, and a trained evaluator present to answer questions and note behavioral observations. Online tests, by contrast, are taken at kitchen tables, on smartphones during lunch breaks, or late at night when fatigue has set in. Each of these variables introduces noise into the results.

A person taking a timed memory test while receiving text messages is not being assessed under the same conditions as the validation studies that established the test’s normative data. A concrete example: research on computer-based cognitive assessments has found that older adults who are less familiar with touchscreens or computer interfaces perform worse on digitally administered tests compared to paper-and-pencil equivalents, even when their cognitive function is equivalent. The test ends up measuring technology comfort as much as cognition. This is not a hypothetical concern — it affects the very populations most likely to be seeking dementia screening. Digital literacy gaps among adults over 75 are well documented, and designing a dementia test primarily around a digital interface introduces systematic bias against the age group most at risk.

What Is the Risk of a False Negative or False Positive From an Online Screening Test?

False negatives — tests that miss real cognitive impairment — are perhaps the more dangerous outcome. Someone with early dementia who scores within the normal range on an online test may delay seeking care, reassured by a result that does not reflect their actual condition. Early intervention in dementia, while not curative for most forms, can significantly affect quality of life, safety planning, legal and financial preparation, and in some cases access to clinical trials. Missing that window matters. The relative insensitivity of brief screening tools to mild cognitive impairment, in particular, means that the earliest and most actionable stage of decline is precisely what these tests are least likely to catch.

False positives carry their own set of harms. Anxiety, unnecessary medical appointments, premature changes to living arrangements, and family disruption can all follow from a misleading test result. There is also a financial dimension: someone who receives a concerning online result may pursue a cascade of additional tests and specialist appointments, at significant cost, ultimately to be told that their cognition is normal. Comparing the two types of error, there is no clean tradeoff — both have real consequences. The appropriate response to either a concerning or a reassuring online test result is the same: consult a qualified clinician rather than acting on the number alone.

Can Online Tests Be Used Responsibly, and What Are the Warning Signs of Misleading Tools?

Some online cognitive tests are better designed than others, and a few have legitimate uses when framed correctly. Research institutions and healthcare systems have developed validated digital cognitive assessments — tools like Cogstate or the BrainCheck platform — that are intended for use within clinical workflows rather than as standalone consumer products. These tools still require clinical interpretation, but they are built on more rigorous psychometric foundations than the average online quiz. The distinction between a research-grade digital assessment and a marketing-forward “brain test” website is significant, though not always obvious to a consumer.

Warning signs of unreliable online dementia tools include: tests that provide an instant diagnosis or tell users they “likely have” or “do not have” dementia; tools with no disclosed validation data or normative comparisons; sites that use results to sell supplements, coaching programs, or paid reports; and assessments that take fewer than three minutes and claim to assess multiple cognitive domains. The commercial incentive to provide definitive-sounding results is real — anxiety drives clicks, and reassurance drives purchases. A responsible screening tool will always direct users toward professional evaluation and will describe its output as a screening flag, not a diagnosis. If a website tells you definitively what you do or do not have based on a brief online quiz, that is a red flag, not a medical opinion.

What Role Should Online Screening Play in the Path to a Dementia Evaluation?

At their best, online dementia screening tools serve one narrow purpose: prompting people who might not otherwise seek care to have a conversation with their doctor. If someone notices cognitive changes, takes an online test, receives a concerning result, and then schedules an appointment with their physician — the tool has done something useful, even if the eventual clinical evaluation reveals no impairment. In this sense, online tests function more like a nudge than a clinical instrument. The problem arises when they are treated as endpoints rather than entry points.

Physicians themselves sometimes administer brief standardized screening tools in primary care — the MoCA or the Mini-Cog, for example — as a starting point when patients or family members express concern. Even these in-person tools, administered by trained clinicians, are understood within the medical community as triggers for further evaluation rather than definitive assessments. The referral pathway from a primary care screening to neuropsychological testing to specialist evaluation exists precisely because the stakes are high and no single tool is sufficient. Online tests sit even further upstream in this chain, which means they should carry proportionally less interpretive weight.

Where Is Online Cognitive Testing Headed, and Will It Improve?

Digital cognitive assessment is a legitimate and growing area of neurological research, and the tools available are likely to improve substantially over the next decade. Researchers are exploring passive monitoring approaches — using smartphone usage patterns, typing speed, voice analysis, and GPS data — to detect subtle longitudinal changes in cognition without requiring any deliberate test-taking. Some of this work is promising and avoids several of the limitations of traditional snapshot assessments by tracking change over time rather than comparing a single result to population norms.

However, these approaches raise significant privacy concerns and are not yet validated for clinical use. The near-term reality is that current consumer-facing online dementia tests remain blunt instruments, and users should approach them accordingly. The field’s scientific progress does not change the nature of today’s available tools. Staying informed about what these tests can and cannot do is the most useful posture for both individuals and family members navigating cognitive health concerns.

Conclusion

Online dementia screening tests have real limitations that users need to understand clearly. They measure a narrow range of cognitive functions, they are affected by environmental and demographic variables that are never accounted for in the results, and they are designed to screen — not diagnose. A concerning score does not mean dementia is present, and a reassuring score does not mean it is absent.

Both kinds of results require the same follow-up: a conversation with a qualified clinician who can evaluate the full picture. The appropriate use of these tools is as a low-stakes prompt to seek professional evaluation, nothing more. If you or someone you care for is experiencing cognitive changes, the most important step is scheduling an appointment with a primary care physician, who can determine whether a referral to a neurologist or neuropsychologist is warranted. Online tests may help frame that conversation, but they cannot replace it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can an online dementia test diagnose Alzheimer’s disease?

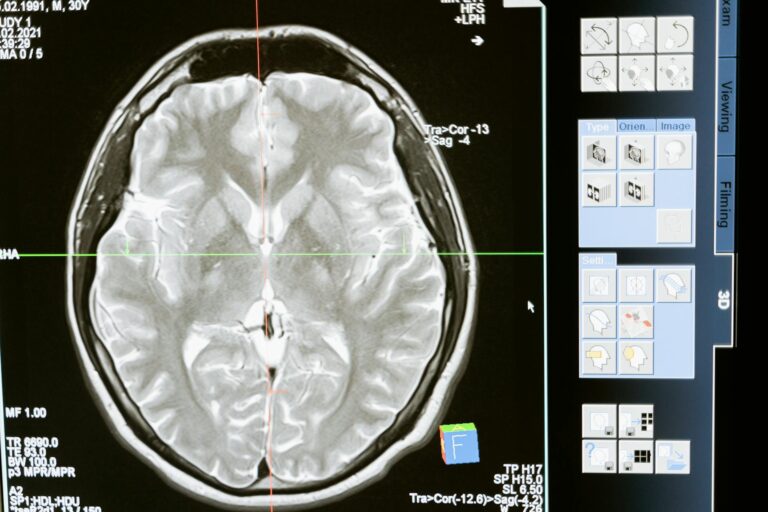

No. No online test can diagnose Alzheimer’s disease or any other form of dementia. Diagnosis requires a comprehensive clinical evaluation that includes medical history, neurological examination, neuropsychological testing, blood work, and often brain imaging. Online tests are screening tools at best, and most consumer-facing versions are not even validated for that limited purpose.

If I score poorly on an online dementia test, should I be worried?

A poor score warrants a follow-up conversation with your doctor, but not panic. Many factors unrelated to dementia — including poor sleep, anxiety, depression, medication effects, thyroid problems, and vitamin deficiencies — can affect cognitive test performance. Your physician can help determine whether further evaluation is needed.

Are there any online cognitive tests that are reliable?

Some digitally administered cognitive assessments used within clinical systems — such as Cogstate or BrainCheck — are more rigorously validated than general consumer tools, but they are still intended to supplement, not replace, clinical evaluation. The free quizzes widely available on general health websites typically lack published validation data and should not be treated as authoritative.

What should I do instead of relying on an online test?

If you are concerned about your memory or someone else’s, speak with a primary care physician. They can administer a brief in-person screening, review relevant medical history, order appropriate bloodwork, and refer to a specialist if indicated. The formal clinical pathway exists because dementia evaluation is genuinely complex and requires trained human judgment.

Can online tests detect mild cognitive impairment (MCI)?

Mild cognitive impairment is particularly difficult to detect with brief screening tools, online or otherwise. MCI involves subtle changes that may be apparent on comprehensive neuropsychological testing but fall within normal ranges on short screeners. This is one of the more significant limitations of any brief cognitive test, and it means that the earliest actionable stage of decline is also the hardest to catch with simple tools.