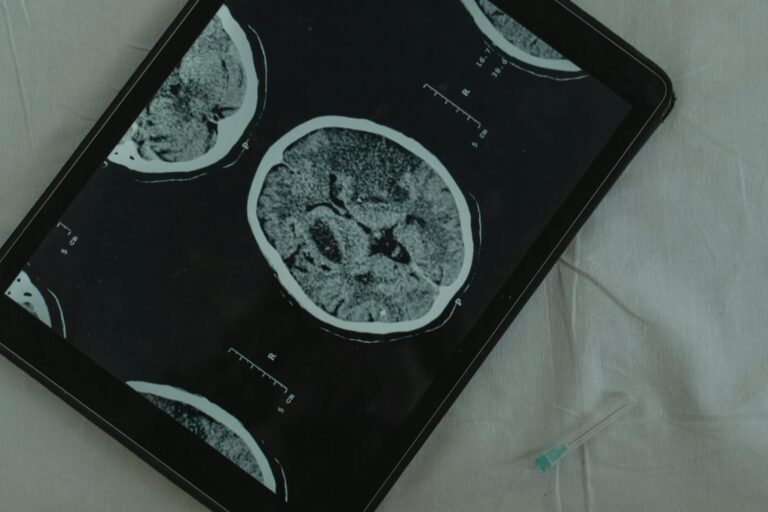

Sleep functions as the brain’s primary waste removal system, and during deep sleep stages, the glymphatic system becomes up to 60% more active in clearing amyloid-beta proteins””the sticky plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. When you sleep, your brain cells actually shrink by about 20%, creating wider channels between neurons that allow cerebrospinal fluid to flush out metabolic waste, including the toxic amyloid proteins that accumulate during waking hours. This isn’t a gradual process; research from the University of Rochester found that amyloid clearance during sleep occurs at roughly twice the rate compared to the wakeful state, making consistent, quality sleep one of the most powerful tools available for brain health maintenance. Consider a 55-year-old accountant who sleeps only five hours nightly during tax season each year.

Brain imaging studies suggest that even short-term sleep deprivation can increase amyloid-beta levels by 5% in just one night, and chronic sleep restriction compounds this burden over time. This individual isn’t just tired””they’re potentially accelerating the same pathological processes seen in early Alzheimer’s disease. The connection between sleep and amyloid clearance represents one of the most significant discoveries in dementia prevention research over the past decade. This article examines the science behind sleep-driven amyloid clearance, explores how different sleep stages contribute to brain cleaning, identifies the consequences of sleep deprivation on cognitive health, and provides practical strategies for optimizing your sleep for maximum brain protection. We’ll also address common sleep disorders that interfere with this process and discuss what current research suggests about reversing amyloid accumulation through improved sleep habits.

Table of Contents

- What Happens to Amyloid Proteins During Sleep?

- The Glymphatic System and Deep Sleep Cycles

- How Sleep Deprivation Accelerates Amyloid Accumulation

- Sleep Apnea and Its Impact on Brain Amyloid Levels

- Sleep Quality Versus Sleep Duration for Brain Health

- The Role of Circadian Rhythm in Amyloid Production

- How to Prepare

- How to Apply This

- Expert Tips

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Happens to Amyloid Proteins During Sleep?

During wakefulness, your neurons are constantly firing, communicating, and producing metabolic byproducts””including amyloid-beta, a protein fragment that serves no known beneficial purpose and tends to clump together into the plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. The brain produces amyloid continuously throughout the day, but it lacks the capacity to efficiently clear this waste while simultaneously managing the demands of conscious thought, movement, and sensory processing. This creates a daily accumulation that must be addressed during sleep. The glymphatic system””named for its dependence on glial cells””activates primarily during sleep, particularly during the slow-wave deep sleep phases. Cerebrospinal fluid pumps through the brain tissue along the outside of blood vessels, mixing with the interstitial fluid that surrounds neurons and literally washing away accumulated waste.

Research published in Science demonstrated that mice cleared amyloid-beta from their brains twice as fast during sleep compared to wakefulness, and subsequent human studies using PET imaging have confirmed similar patterns. When comparing a well-rested brain to a sleep-deprived one, the difference in amyloid burden can be measured after just a single night. However, this clearance mechanism has limitations. The glymphatic system operates optimally only during specific sleep stages and body positions””side sleeping appears to enhance clearance compared to sleeping on your back or stomach. Additionally, the system’s efficiency naturally declines with age, meaning older adults may need even more quality sleep to achieve the same clearance rates they experienced in younger years. This age-related decline in glymphatic function may partially explain why Alzheimer’s risk increases so dramatically after age 65.

The Glymphatic System and Deep Sleep Cycles

Deep sleep, also called slow-wave sleep or N3 stage sleep, represents the most critical period for amyloid clearance. During this phase, brain waves slow to their lowest frequency, neural activity becomes synchronized, and the glymphatic system reaches peak efficiency. Adults typically cycle through deep sleep two to three times per night, with the longest deep sleep periods occurring in the first half of the night. This timing has practical implications: if you go to bed late but wake at the same time, you’re disproportionately cutting into your deep sleep rather than simply losing sleep across all stages. The relationship between deep sleep and clearance is not merely correlational. When researchers at Washington University artificially disrupted slow-wave sleep in healthy participants without reducing total sleep time, amyloid-beta levels in cerebrospinal fluid increased significantly the following day.

This experiment demonstrated that it’s specifically deep sleep””not just sleep duration””that drives the clearance process. Someone sleeping eight hours but experiencing fragmented sleep with minimal deep sleep phases may have worse amyloid clearance than someone sleeping six consolidated hours with robust slow-wave activity. However, if you’re over 60, achieving adequate deep sleep becomes increasingly challenging regardless of your habits. Deep sleep naturally decreases with age, from roughly 20% of total sleep time in young adults to sometimes less than 5% in those over 70. This biological reality means that older adults face a double burden: declining glymphatic efficiency combined with reduced access to the sleep stages that drive clearance. Medications, alcohol, and sleep disorders further compound this problem, making sleep optimization particularly critical for aging populations.

How Sleep Deprivation Accelerates Amyloid Accumulation

The consequences of insufficient sleep on amyloid accumulation are measurable and cumulative. A landmark 2018 study from the National Institutes of Health found that losing just one night of sleep increased amyloid-beta accumulation in the human brain by approximately 5%, concentrated in the thalamus and hippocampus””regions critical for memory consolidation. While the brain can partially compensate for occasional sleep loss through rebound deep sleep, chronic sleep deprivation doesn’t allow for full recovery, leading to progressive amyloid buildup. Consider the difference between someone who consistently sleeps seven to eight hours versus someone averaging five to six hours over years or decades. Population studies have found that individuals sleeping fewer than six hours nightly in midlife have a 30% higher risk of developing dementia compared to those sleeping seven hours.

While multiple factors contribute to this increased risk, impaired amyloid clearance appears to be a primary mechanism. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease, while debated, suggests that this accumulation begins decades before clinical symptoms appear, making midlife sleep habits particularly consequential. Importantly, the relationship between sleep and amyloid is bidirectional””another complicating factor for those already experiencing accumulation. As amyloid plaques build up in the brain, they disrupt the neural circuits that regulate sleep, causing increased nighttime awakenings, reduced deep sleep, and altered circadian rhythms. This creates a vicious cycle where amyloid impairs sleep, which impairs clearance, which accelerates further accumulation. Breaking this cycle early, before significant plaque formation occurs, appears far more effective than attempting to reverse established accumulation through improved sleep alone.

Sleep Apnea and Its Impact on Brain Amyloid Levels

Obstructive sleep apnea affects an estimated 30 million Americans and represents one of the most significant modifiable risk factors for accelerated amyloid accumulation. During apnea episodes, breathing stops repeatedly throughout the night””sometimes hundreds of times””causing oxygen levels to drop and sleep architecture to fragment. Even when total sleep time appears adequate, the repeated arousals prevent the brain from achieving and maintaining the deep sleep necessary for effective glymphatic function. Research from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative found that individuals with untreated sleep apnea showed significantly higher amyloid burden on PET scans compared to age-matched controls, and that the severity of apnea correlated with the degree of accumulation.

More encouragingly, studies examining CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) therapy have demonstrated that consistent treatment can slow or potentially halt this accelerated accumulation. One study following older adults over two years found that those who used CPAP regularly showed stable amyloid levels, while untreated apnea patients showed continued accumulation. A specific example illustrates the stakes: a 60-year-old man diagnosed with moderate sleep apnea who chooses not to pursue treatment because he feels “fine” during the day may be experiencing 30 or more complete or partial breathing stoppages per hour of sleep. Each event fragments his sleep architecture, prevents deep sleep maintenance, and keeps his glymphatic system from functioning optimally””all while he remains unaware of any problem beyond occasional tiredness. The asymptomatic nature of early amyloid accumulation means that damage can progress for years before any cognitive symptoms emerge.

Sleep Quality Versus Sleep Duration for Brain Health

The distinction between sleep quantity and sleep quality matters enormously for amyloid clearance, though both remain important. Someone sleeping nine hours while experiencing frequent awakenings, spending excessive time in light sleep stages, or dealing with undiagnosed sleep disorders may achieve worse clearance than someone sleeping seven consolidated hours with appropriate cycling through all sleep stages. Quality metrics include sleep efficiency (percentage of time in bed actually sleeping), time spent in deep sleep, sleep continuity, and the natural progression through sleep cycles. When comparing strategies, extending sleep duration offers diminishing returns beyond a certain point””sleeping ten hours won’t clear amyloid twice as effectively as sleeping seven hours. In fact, studies have found that very long sleep durations (over nine hours) in older adults are associated with increased dementia risk, though this likely reflects underlying health problems causing excessive sleep rather than any direct harm from sleep itself.

The optimal target for most adults appears to be seven to eight hours of actual sleep time, with the emphasis on ensuring that sleep is consolidated and includes adequate deep sleep phases. Alcohol exemplifies the quality-versus-quantity tradeoff. A nightcap may help someone fall asleep faster, but alcohol suppresses REM sleep and reduces deep sleep phases, particularly in the second half of the night. Someone who drinks a glass of wine before bed might achieve seven hours of sleep but with significantly impaired clearance compared to the same seven hours without alcohol. Similarly, sleep medications like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or zolpidem (Ambien) may increase total sleep time while actually reducing the deep sleep stages most critical for brain cleaning.

The Role of Circadian Rhythm in Amyloid Production

Amyloid-beta production and clearance follow a circadian pattern that aligns with the sleep-wake cycle, adding another layer of complexity to brain health maintenance. Research has shown that amyloid levels in cerebrospinal fluid fluctuate throughout the day, peaking in the evening and declining overnight during sleep. Disrupting this rhythm through shift work, jet lag, or irregular sleep schedules can impair the brain’s ability to coordinate production and clearance effectively. Night shift workers provide a particularly concerning example. Studies of nurses, factory workers, and others who regularly work overnight shifts have found elevated markers of neuroinflammation and altered amyloid metabolism compared to day-shift workers.

A nurse working three overnight shifts per week for twenty years isn’t just losing sleep””she’s chronically disrupting the circadian signals that regulate glymphatic function. Her brain may be producing amyloid when it should be clearing it and attempting clearance when metabolic conditions aren’t optimal. Maintaining consistent sleep timing””going to bed and waking at roughly the same times daily””appears to support optimal amyloid clearance even when controlling for total sleep duration. The brain’s clearance mechanisms function best when they can anticipate sleep onset and prepare the glymphatic system accordingly. Weekend sleep schedule variations of more than two hours from weekday patterns can create a form of chronic circadian disruption that impairs this coordination.

How to Prepare

- **Set your bedroom temperature between 65-68 degrees Fahrenheit.** The body’s core temperature must drop slightly to initiate and maintain deep sleep, and a cool room facilitates this process. Research from the National Sleep Foundation indicates that temperatures above 70 degrees significantly reduce time spent in slow-wave sleep.

- **Eliminate all light sources, including small LEDs from electronics.** Even dim light exposure during sleep can suppress melatonin production and fragment sleep architecture. Use blackout curtains and cover or remove any devices with indicator lights.

- **Establish a consistent sleep schedule, maintaining the same bedtime and wake time within 30 minutes daily, including weekends.** This consistency strengthens circadian rhythms and helps the brain anticipate and prepare for the clearance process.

- **Remove or silence all electronic devices capable of producing alerts.** A single notification that partially rouses you from sleep can disrupt the deep sleep phases necessary for optimal amyloid clearance, even if you don’t fully wake.

- **Evaluate your mattress and pillow for proper support and consider sleeping on your side.** Research suggests that lateral sleeping positions may enhance glymphatic drainage compared to supine or prone positions.

How to Apply This

- **Stop all caffeine consumption by early afternoon””no later than 2 PM for most people.** Caffeine has a half-life of approximately five hours, meaning that coffee at 4 PM still affects sleep architecture at midnight. Even if you can fall asleep after caffeine, studies show reduced deep sleep phases.

- **Avoid alcohol for at least three hours before bed, recognizing that any alcohol consumption reduces sleep quality.** If you currently use alcohol as a sleep aid, expect a transition period of several nights of worse sleep as your body adjusts to falling asleep without sedation.

- **Expose yourself to bright light””preferably natural sunlight””within the first hour of waking.** This anchors your circadian rhythm and helps establish appropriate timing for melatonin release in the evening, which supports sleep onset and architecture.

- **Complete any vigorous exercise at least four hours before bedtime while maintaining regular physical activity.** Exercise improves sleep quality substantially but causes physiological arousal that can impair sleep if performed too close to bedtime.

Expert Tips

- Maintain a sleep diary for two weeks to identify patterns you might otherwise miss””many people significantly overestimate their actual sleep time and underestimate nighttime awakenings.

- If you snore, gasp during sleep, or wake with headaches, pursue formal evaluation for sleep apnea even if you feel rested, as this condition often goes undiagnosed for years while causing neurological damage.

- Do not use over-the-counter sleep aids containing diphenhydramine or doxylamine regularly, as these anticholinergic medications have been associated with increased dementia risk and impair natural sleep architecture.

- Consider cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) rather than medication if you struggle with sleep””CBT-I produces longer-lasting improvements and enhances natural sleep quality rather than simply inducing sedation.

- Recognize that napping, while sometimes necessary, reduces sleep pressure and can impair nighttime deep sleep, particularly if naps exceed 30 minutes or occur after 3 PM.

Conclusion

The relationship between sleep and amyloid clearance represents one of the most actionable findings in dementia prevention research. Your brain possesses a sophisticated waste removal system that activates during sleep, and this system clears the same toxic proteins implicated in Alzheimer’s disease at dramatically higher rates during quality sleep than during wakefulness. Every night of adequate deep sleep contributes to ongoing brain maintenance, while chronic sleep deprivation allows progressive accumulation that may take years to manifest as cognitive symptoms.

Prioritizing sleep is not a luxury or a sign of low productivity””it’s a biologically necessary maintenance process without which your brain cannot function optimally or protect itself from neurodegeneration. The strategies outlined here””environmental optimization, behavioral changes, treatment of sleep disorders, and consistent scheduling””all work toward the same goal of maximizing the time your glymphatic system spends actively clearing metabolic waste. For anyone concerned about cognitive aging or with a family history of dementia, sleep quality deserves at least as much attention as diet, exercise, or cognitive stimulation.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it typically take to see results?

Results vary depending on individual circumstances, but most people begin to see meaningful progress within 4-8 weeks of consistent effort. Patience and persistence are key factors in achieving lasting outcomes.

Is this approach suitable for beginners?

Yes, this approach works well for beginners when implemented gradually. Starting with the fundamentals and building up over time leads to better long-term results than trying to do everything at once.

What are the most common mistakes to avoid?

The most common mistakes include rushing the process, skipping foundational steps, and failing to track progress. Taking a methodical approach and learning from both successes and setbacks leads to better outcomes.

How can I measure my progress effectively?

Set specific, measurable goals at the outset and track relevant metrics regularly. Keep a journal or log to document your journey, and periodically review your progress against your initial objectives.

When should I seek professional help?

Consider consulting a professional if you encounter persistent challenges, need specialized expertise, or want to accelerate your progress. Professional guidance can provide valuable insights and help you avoid costly mistakes.

What resources do you recommend for further learning?

Look for reputable sources in the field, including industry publications, expert blogs, and educational courses. Joining communities of practitioners can also provide valuable peer support and knowledge sharing.