Yes, Parkinson’s disease significantly increases the risk of broken bones, with research consistently showing that people with Parkinson’s face approximately two to three times the fracture risk of the general population. This elevated risk stems from a combination of factors unique to the disease: motor symptoms like tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia (slowness of movement) make falls more likely, while the disease itself and some medications used to treat it can weaken bone density over time. Hip fractures are particularly concerning, as they occur with notably higher frequency in Parkinson’s patients and carry serious consequences for mobility and independence. Consider a 72-year-old man with moderate Parkinson’s who experiences a freezing episode””a sudden, temporary inability to move””while walking to his bathroom at night. This common scenario illustrates how the disease creates perfect conditions for falls and subsequent fractures.

His shuffling gait, impaired balance, and delayed reflexes mean he cannot catch himself when he stumbles. Unlike someone without Parkinson’s who might recover their footing, he falls directly onto his hip. If his bones have also been weakened by reduced activity and vitamin D deficiency from spending more time indoors, a fracture becomes almost inevitable. This article explores the specific mechanisms connecting Parkinson’s disease to fracture risk, examines which bones are most vulnerable, and provides practical strategies for reducing this risk. We will also discuss how medications, both for Parkinson’s and for bone health, play into this equation, and when caregivers and patients should seek specialized assessment.

Table of Contents

- Why Does Parkinson’s Disease Lead to More Falls and Fractures?

- Which Bones Are Most Commonly Broken in People With Parkinson’s?

- How Do Parkinson’s Medications Affect Bone Health?

- What Practical Steps Can Reduce Fracture Risk in Parkinson’s Patients?

- What Are the Challenges of Treating Fractures in People With Parkinson’s?

- The Role of Bone Density Screening in Parkinson’s Disease

- Future Directions in Fracture Prevention for Parkinson’s Patients

- Conclusion

Why Does Parkinson’s Disease Lead to More Falls and Fractures?

The connection between Parkinson’s disease and broken bones operates through two distinct but interrelated pathways: increased fall frequency and decreased bone strength. Understanding both is essential for effective prevention. Motor symptoms are the most obvious culprits””postural instability develops as the disease progresses, and the characteristic stooped posture shifts the body’s center of gravity forward, making recovery from any loss of balance extremely difficult. Freezing of gait, which affects roughly half of all Parkinson’s patients at some point, creates sudden, unexpected stops that can send a person tumbling forward. Beyond the motor symptoms, Parkinson’s disease appears to affect bone health directly. Studies have found that people with Parkinson’s have lower bone mineral density than age-matched controls, even when accounting for reduced physical activity.

Some researchers believe this may relate to the disease’s effects on the autonomic nervous system or to chronic vitamin D deficiency, which is common in Parkinson’s patients who become less mobile and spend less time outdoors. Compared to someone with essential tremor, another movement disorder that causes shaking but not the same postural problems, a person with Parkinson’s faces substantially higher fracture risk””highlighting that it is not simply having a movement disorder that matters, but the specific constellation of Parkinson’s symptoms. The timing of falls also matters. Many Parkinson’s-related falls occur during medication “off” periods, when dopaminergic drugs are wearing off and symptoms temporarily worsen. Falls are also more common during transitions””getting up from a chair, turning while walking, or navigating obstacles. These patterns have implications for prevention strategies, suggesting that careful attention to medication timing and environmental modifications may help reduce risk.

Which Bones Are Most Commonly Broken in People With Parkinson’s?

Hip fractures represent the most serious fracture type in the Parkinson’s population, occurring at rates historically reported as two to four times higher than in people without the disease. The consequences extend far beyond the bone itself: hip fractures in Parkinson’s patients are associated with prolonged hospital stays, higher rates of complications, reduced likelihood of returning to independent living, and increased mortality in the year following the fracture. The surgery required to repair a hip fracture also poses particular challenges in Parkinson’s patients, who may experience worsening confusion or motor symptoms during hospitalization. Wrist and forearm fractures are also common, typically occurring when someone extends their arms to break a fall.

Vertebral compression fractures, though sometimes overlooked because they can occur without an obvious fall, affect many older adults with Parkinson’s and contribute to the progressive stooped posture that further impairs balance. However, if someone with Parkinson’s experiences a fracture from minimal trauma””such as a simple fall from standing height or even just bending over””this should prompt evaluation for osteoporosis, as it suggests bone density may be significantly compromised beyond what the fall alone would explain. It is worth noting that fracture risk is not uniform across all Parkinson’s patients. Those with more advanced disease, significant postural instability, cognitive impairment, or a history of previous falls face the highest risk. Conversely, someone in the early stages of Parkinson’s with well-controlled symptoms and good bone density may have only modestly elevated fracture risk compared to peers without the disease.

How Do Parkinson’s Medications Affect Bone Health?

The relationship between Parkinson’s medications and bone health is complex, with both potential benefits and risks. Levodopa, the most effective and widely used Parkinson’s medication, has been studied extensively for its effects on bone. Some research has suggested that levodopa might contribute to bone loss through its effects on homocysteine levels””an amino acid that, when elevated, may interfere with bone formation. However, other studies have found that better motor symptom control through adequate levodopa dosing actually protects bones by enabling more physical activity and reducing falls. Dopamine agonists, another class of Parkinson’s medications, have been associated with compulsive behaviors in some patients, including compulsive eating that might lead to weight changes affecting bone health.

More directly relevant, these medications can cause orthostatic hypotension””a sudden drop in blood pressure upon standing””which itself is a major fall risk factor. For example, a patient who feels lightheaded every time she stands up from her chair is at substantial risk for falling during that vulnerable moment, regardless of how well her other Parkinson’s symptoms are controlled. Medications used to treat Parkinson’s-related conditions may also play a role. Antipsychotic medications sometimes prescribed for Parkinson’s psychosis, antidepressants for the depression that commonly accompanies the disease, and sleep medications for Parkinson’s-related insomnia have all been associated with increased fall risk in older adults. This creates a clinical dilemma: these medications may be genuinely needed to manage distressing symptoms, but their use requires careful consideration of fall and fracture risk, ideally with strategies to mitigate that risk.

What Practical Steps Can Reduce Fracture Risk in Parkinson’s Patients?

Preventing fractures in Parkinson’s disease requires a multi-pronged approach addressing both fall prevention and bone health. Physical therapy specifically designed for Parkinson’s patients has demonstrated benefits for gait, balance, and functional mobility. Programs incorporating exercises that challenge balance in a safe environment””such as tai chi, which has been studied in Parkinson’s populations with promising results””may be particularly valuable. The tradeoff is that exercise programs must be intensive enough to produce benefits but not so challenging that they themselves cause falls during training. Home safety modifications can eliminate many fall hazards. Removing loose rugs, improving lighting (especially in bathrooms and hallways used at night), installing grab bars near toilets and showers, and ensuring clear pathways through the home are fundamental steps.

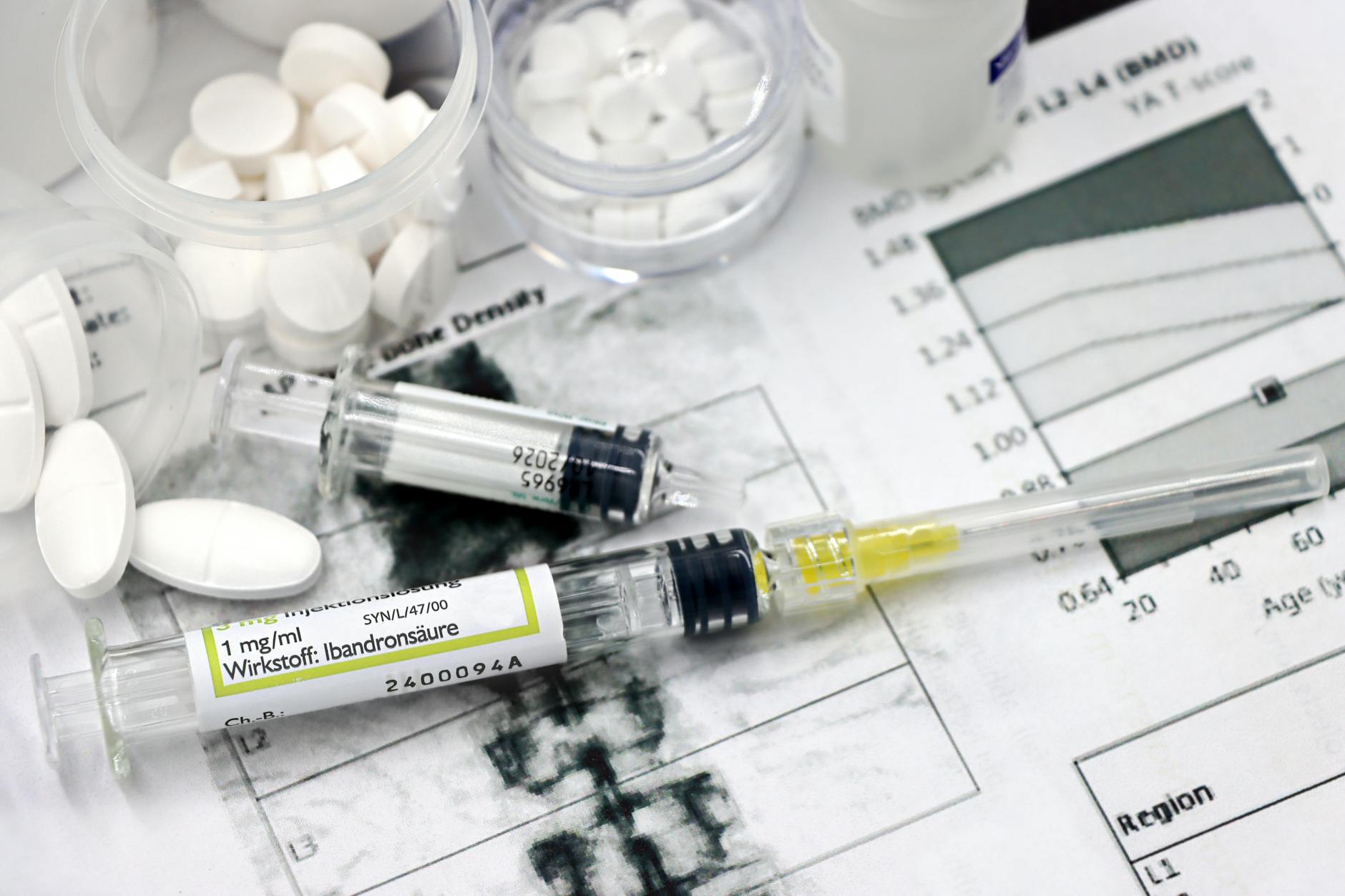

Occupational therapists can conduct home assessments to identify specific risks. For someone who experiences freezing episodes, visual cues like tape strips on the floor can sometimes help initiate movement, while laser pointers attached to walking devices have shown benefit in some patients. Bone health interventions parallel those recommended for the general older adult population but take on greater urgency given Parkinson’s patients’ elevated fracture risk. Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake””through diet, supplements, or both””supports bone maintenance. Bisphosphonates and other osteoporosis medications may be appropriate for patients with documented low bone density, though these medications have their own considerations regarding duration of use and potential side effects. A bone density scan (DEXA) provides objective information to guide these decisions, and many experts recommend that people newly diagnosed with Parkinson’s undergo baseline bone density assessment.

What Are the Challenges of Treating Fractures in People With Parkinson’s?

When fractures do occur in Parkinson’s patients, treatment and recovery present unique challenges. Hospitalization for fracture repair can disrupt the careful medication timing that many patients rely on to manage their symptoms. Parkinson’s medications must often be given at precise intervals, yet hospital routines may not accommodate this need. Patients and caregivers should advocate strongly for continuation of the home medication schedule during hospitalization, as missed or delayed doses can cause significant symptom worsening. Anesthesia and surgery pose additional considerations. Some anesthetic agents can interact with Parkinson’s medications, and the stress of surgery can temporarily worsen symptoms.

Post-operative delirium””sudden confusion after surgery””occurs more frequently in Parkinson’s patients and can complicate recovery. Pain management also requires thought, as certain pain medications can affect cognition or interact with Parkinson’s drugs. Patients should ensure that their surgical and anesthesia teams are aware of their Parkinson’s diagnosis and current medication regimen. Rehabilitation after a fracture is typically longer and more challenging for people with Parkinson’s compared to those without the disease. The motor impairments that contributed to the fall in the first place also slow the recovery process. Physical therapy remains essential, but expectations should be calibrated to the individual’s overall disease status. Some patients regain their previous level of function, while others, particularly those with more advanced Parkinson’s or cognitive impairment, may experience a permanent decline in mobility following a major fracture.

The Role of Bone Density Screening in Parkinson’s Disease

Bone density testing through DEXA scanning offers valuable information for Parkinson’s patients and their healthcare providers, yet it remains underutilized in this population. Standard osteoporosis screening guidelines typically focus on postmenopausal women and older men but may not specifically flag Parkinson’s disease as a risk factor requiring earlier or more frequent screening. Given the elevated fracture risk in Parkinson’s, many movement disorder specialists recommend bone density assessment at the time of Parkinson’s diagnosis, with follow-up testing based on initial results and other risk factors.

For example, a 65-year-old woman newly diagnosed with Parkinson’s who also has a family history of osteoporosis, a small body frame, and limited sun exposure might benefit significantly from knowing her baseline bone density. If testing reveals osteopenia (mildly reduced bone density) or osteoporosis, she and her physician can implement bone-protective strategies early, potentially preventing fractures that might otherwise occur years down the road. The cost and radiation exposure from DEXA scanning are minimal compared to the potential benefits of early intervention.

Future Directions in Fracture Prevention for Parkinson’s Patients

Research continues to explore better approaches to reducing fracture risk in Parkinson’s disease. Wearable technology that can detect changes in gait patterns and predict falls before they occur represents one promising avenue””such devices might eventually alert patients or caregivers when fall risk is particularly high, such as during medication off periods. Studies are also investigating whether certain Parkinson’s treatments might have bone-protective effects, potentially influencing medication selection.

The integration of fracture prevention into routine Parkinson’s care appears to be improving, with greater awareness among neurologists and movement disorder specialists about the importance of addressing bone health alongside motor symptoms. Multidisciplinary care models that bring together neurologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and primary care physicians offer comprehensive approaches to this multifaceted problem. For patients and families, staying informed about fracture risk and advocating for appropriate screening and prevention measures remains important.

Conclusion

Parkinson’s disease substantially increases fracture risk through the dual mechanisms of increased falls and decreased bone strength. Understanding this connection empowers patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers to take meaningful preventive action. From physical therapy and home safety modifications to bone density screening and appropriate medication management, multiple strategies can help reduce the likelihood of a fracture that could significantly impact quality of life and independence.

The key takeaways are to address fracture risk proactively rather than waiting for a fall to occur, to advocate for bone density testing and appropriate treatment if osteoporosis is present, and to work with healthcare providers to minimize fall risk while adequately treating Parkinson’s symptoms. For those who have already experienced a fracture, ensuring proper medication management during hospitalization and engaging in rehabilitation can support the best possible recovery. Fractures are not an inevitable consequence of Parkinson’s disease””with attention and appropriate interventions, their likelihood can be meaningfully reduced.