High blood pressure damages the brain through multiple overlapping mechanisms — and the harm begins far earlier than most people realize. The primary pathways involve the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, destruction of the brain’s white matter wiring, disruption of the delicate balance between neurons, and progressive reduction in blood flow to brain tissue. The cumulative result is measurable cognitive decline, increased dementia risk, and structural brain changes that can begin accumulating years or even decades before a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia.

For context, consider a 55-year-old with untreated hypertension who feels cognitively sharp — research suggests silent structural damage may already be underway in the brain’s memory and reasoning regions. The risk is neither abstract nor rare. Nearly 50 percent of American adults have hypertension, and it is considered the single most important modifiable vascular risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. This article explains how blood pressure physically alters brain tissue, why white matter is especially vulnerable, what recent research has revealed about the timeline of damage, how blood pressure fluctuations compound the problem, and what treatment evidence exists for reversing early harm.

Table of Contents

- What Does High Blood Pressure Actually Do to Brain Tissue Over Time?

- Why White Matter Is Particularly Vulnerable to Blood Pressure Damage

- How Hypertension Creates a Neuronal Imbalance Similar to Alzheimer’s Disease

- Blood Pressure Fluctuations May Be as Damaging as Consistently High Readings

- The Dementia Risk Numbers — And Why Midlife Hypertension Is the Critical Window

- What Existing Treatments Tell Us About Reversibility

- A Changing Understanding of When Brain Risk Begins

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Does High Blood Pressure Actually Do to Brain Tissue Over Time?

The brain depends on a tightly regulated blood supply. The blood-brain barrier — a specialized layer of endothelial cells lining the brain’s blood vessels — normally acts as a selective filter, keeping toxins, pathogens, and inflammatory molecules out of neural tissue. Hypertension puts chronic mechanical stress on this barrier. Over time, it disrupts the tight junctions between endothelial cells, creating gaps that allow harmful molecules to leak into brain tissue. Once those molecules reach neurons and supporting cells, they trigger inflammation, oxidative stress, and eventual cell death. The endothelial cells themselves suffer lasting damage.

Under sustained high pressure, they exhibit premature aging — a state called cellular senescence, where cells stop dividing, lose normal function, and secrete inflammatory signals that harm neighboring tissue. They also show lower energy metabolism, meaning the cells can no longer maintain the barrier as efficiently. Think of it like the mortar between bricks slowly crumbling: the wall stays upright for a while, but it becomes progressively less effective at keeping water out until the structural damage becomes impossible to ignore. Beyond the barrier, hypertension reduces overall cerebral blood flow — a process called hypoperfusion. The brain is metabolically expensive and cannot tolerate oxygen deprivation for long. Chronic underperfusion forces brain regions to operate under persistent low-grade stress, slowly degrading their function and structure even without a discrete stroke or injury event.

Why White Matter Is Particularly Vulnerable to Blood Pressure Damage

White matter is the brain’s internal communication network — bundles of myelinated axons that connect different regions and allow fast, coordinated processing. It handles tasks like working memory, problem-solving speed, and executive function. It is also disproportionately vulnerable to the type of damage hypertension causes, in part because it relies on small blood vessels that are less able to self-regulate under pressure fluctuations. Research published by Cambridge’s Cam-CAN project in 2025 found that high pulse pressure — the numerical gap between systolic and diastolic readings — specifically impairs cognition by damaging white matter. A person with a systolic of 160 and diastolic of 70 has a pulse pressure of 90, well above the roughly 40 considered normal.

That wider gap reflects stiffer arteries, which transmit more mechanical force into smaller vessels and into white matter tissue. Over years, this translates to white matter lesions: patches of damaged tissue visible on MRI that are associated with slower thinking, memory lapses, and eventually dementia. However, the relationship between white matter damage and symptoms is not always linear. Some individuals accumulate substantial white matter lesions with relatively mild cognitive complaints, while others show pronounced deficits with fewer visible lesions. This suggests that white matter damage interacts with cognitive reserve — the brain’s ability to compensate through redundant pathways — and that lesion location matters as much as lesion volume. Damage to strategic connection hubs is far more functionally disruptive than an equivalent volume of damage in less critical regions.

How Hypertension Creates a Neuronal Imbalance Similar to Alzheimer’s Disease

The brain’s function depends on a precise balance between neurons that excite activity and neurons that inhibit it. Interneurons — specialized cells that regulate this inhibitory side of the equation — are among the earliest casualties of hypertension-induced brain damage. When interneurons are damaged or lost, the excitatory-inhibitory balance tips, and neural circuits become dysregulated. This is not merely an academic observation. A November 2025 study from Weill Cornell Medicine found that in mice, key brain cells — including endothelial cells, interneurons, and white matter — were already showing damage just three days after hypertension was induced, before blood pressure had even measurably risen by conventional measures.

The speed of the change was unexpected and challenges the assumption that brain damage from hypertension is a slow, decades-long process that only matters in old age. The interneuron disruption observed in these mice mirrors patterns seen in Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting a shared neurological mechanism between hypertension-related vascular damage and the neurodegenerative changes associated with Alzheimer’s. This overlap may help explain why hypertension in midlife is such a consistent predictor of Alzheimer’s diagnoses decades later. For a practical example: a person treated aggressively for hypertension starting in their 40s is protecting not just their heart but also the interneuron populations that maintain cognitive stability into their 70s and 80s. The two conditions are not separate risks — they are linked by the same cellular cascade.

Blood Pressure Fluctuations May Be as Damaging as Consistently High Readings

Conventional blood pressure monitoring captures a snapshot — one reading at a clinic visit, perhaps repeated a few times a year. But research from USC published in October 2025 raised a distinct concern: it is not only average blood pressure levels that damage the brain, but also the moment-to-moment variability of blood pressure measured over minutes. Rapid fluctuations — the kind that occur throughout the course of a normal day — were found to correlate with loss of brain tissue in regions associated with memory and cognition, as well as elevated blood biomarkers indicating nerve cell damage. This matters practically because a patient whose average blood pressure appears controlled on standard office measurements may still have significant variability between those readings. Someone whose pressure spikes with stress, exertion, or poor sleep and then drops sharply may be experiencing repeated small insults to the cerebrovascular system that a routine check never captures.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring — a device worn for 24 hours — gives a more complete picture and is increasingly recommended for patients with signs of cognitive decline or white matter changes on imaging. The tradeoff here is one of clinical practicality versus precision. Standard office blood pressure measurement is easy, inexpensive, and widely available. Ambulatory monitoring is more burdensome and not always covered by insurance. For most patients, aggressive management of average blood pressure remains the primary intervention. But for those with borderline-controlled hypertension and cognitive symptoms, the variability question deserves attention — and the USC findings suggest that tools measuring short-term fluctuations may eventually become a standard part of brain health assessment.

The Dementia Risk Numbers — And Why Midlife Hypertension Is the Critical Window

The link between hypertension and dementia is among the most replicated findings in epidemiology. The Honolulu Asia Aging Study found a three- to four-fold elevated risk of dementia in individuals with untreated elevated systolic or diastolic blood pressure. The National Institute on Aging has formally recognized high blood pressure as a key contributor to cognitive decline. These are not marginal associations — a three- to four-fold elevation is a dramatic risk increase by the standards of chronic disease epidemiology. What has become increasingly clear is that the timing of hypertension matters as much as its severity. Hypertension in midlife — roughly ages 40 to 65 — appears to carry a higher dementia risk than hypertension that develops in old age.

This is counterintuitive to many patients, who assume that cognitive decline is primarily a late-life problem. The explanation likely involves the cumulative duration of vascular insult: a brain exposed to high pressure for 20 or 30 years accumulates more damage than one exposed for 5 or 10 years, even if the blood pressure numbers are similar. A warning worth emphasizing: some studies have shown that in adults over 80, very aggressive blood pressure lowering is associated with worse cognitive outcomes, not better ones. An aging brain may become dependent on higher perfusion pressure to maintain adequate blood flow through stiffened, narrowed vessels. This is a meaningful clinical tradeoff — the goal of treatment in very elderly patients is not necessarily the same as in a 50-year-old. Treatment decisions require individualization, and patients should discuss targets with their physicians rather than assuming lower is always better at every age.

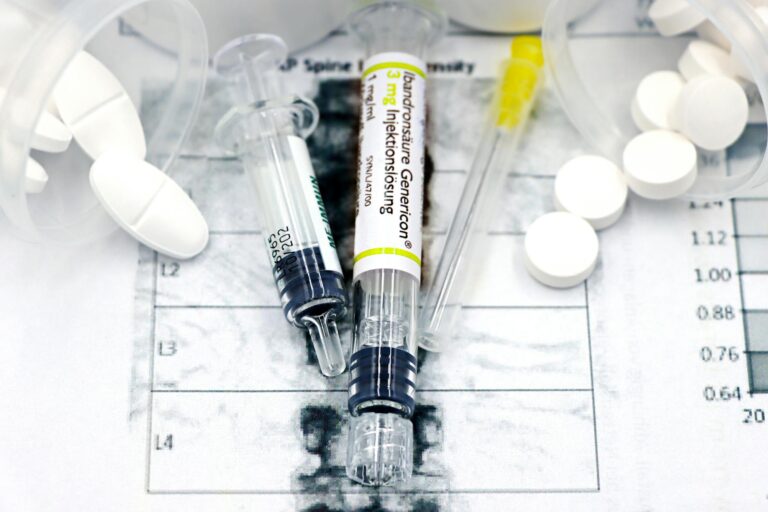

What Existing Treatments Tell Us About Reversibility

The Weill Cornell mouse study that found hypertension-induced brain changes within three days of elevated pressure also provided an encouraging finding: treatment with losartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) commonly used in humans, reversed the early changes to endothelial cells and interneurons. The drug did not merely halt further damage — it appeared to allow recovery of early cellular changes, at least in the animal model. This adds to existing evidence from human clinical trials showing that antihypertensive treatment reduces the incidence of dementia and slows the progression of white matter lesions.

It does not eliminate risk entirely — existing structural damage cannot always be undone — but early, sustained treatment meaningfully changes the trajectory. The practical implication is that the earlier hypertension is identified and treated, the more brain tissue is likely preserved. Waiting until cognitive symptoms emerge to address blood pressure is, in effect, acting after substantial damage has already accumulated.

A Changing Understanding of When Brain Risk Begins

The most significant shift in the science over the past several years is the recognition that the timeline of hypertension-related brain damage is earlier and faster than previously assumed. The Weill Cornell 2025 research showing measurable brain cell changes within days of induced hypertension — before blood pressure even registers as elevated by conventional measurement — suggests that the brain is exquisitely sensitive to vascular disruption at a cellular level, and that waiting for a hypertension diagnosis to act on cardiovascular risk factors may already represent a delayed response.

Future research will likely focus on identifying biomarkers that can detect early vascular brain injury before symptoms emerge, developing better tools for measuring blood pressure variability, and understanding which antihypertensive drug classes offer the most neuroprotection beyond their blood-pressure-lowering effect. For the half of American adults living with hypertension today, the message from the science is increasingly clear: the brain is always downstream of the heart, and what happens in the arteries does not stay in the arteries.

Conclusion

High blood pressure damages the brain through a combination of blood-brain barrier disruption, white matter destruction, reduced cerebral blood flow, and neuronal imbalance — and that damage begins earlier, and progresses faster, than most patients or clinicians have historically assumed. The three- to four-fold elevated dementia risk associated with untreated hypertension is not inevitable, but avoiding it requires sustained management that begins well before any cognitive symptoms appear. White matter lesions, interneuron damage, endothelial aging, and blood pressure variability are all measurable contributors to the same downstream outcome: a brain that is less capable of sustaining memory, reasoning, and cognitive function into older age.

For individuals with hypertension, the most actionable step remains consistent blood pressure control, with a particular emphasis on midlife management. For those with controlled average readings but cognitive concerns, discussing ambulatory blood pressure monitoring with a physician is worth considering given what the 2025 USC research found about variability. For clinicians and caregivers working with dementia patients, the hypertension history is not merely a cardiovascular footnote — it is likely a direct contributor to the neurological picture, and in some cases, a reversible one if identified early enough.

Frequently Asked Questions

At what age does high blood pressure start damaging the brain?

Research suggests damage can begin within days of blood pressure rising at the cellular level, even before conventional measurements detect hypertension. Midlife hypertension — between ages 40 and 65 — carries particularly high long-term dementia risk because of the duration of cumulative exposure.

Can lowering blood pressure reverse brain damage?

Some early cellular changes appear reversible. The drug losartan reversed hypertension-induced damage to endothelial cells and interneurons in a 2025 mouse study. In humans, antihypertensive treatment reduces the rate of new white matter lesions and lowers dementia incidence, though established structural damage is not fully reversed.

Is high blood pressure the biggest risk factor for dementia?

It is considered the most important modifiable vascular risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia — meaning it is the leading risk factor among those a person can actually change through lifestyle or medication.

Does pulse pressure matter for brain health, or just systolic and diastolic numbers?

Yes. High pulse pressure — a wide gap between systolic and diastolic readings — is specifically associated with white matter damage and cognitive impairment, independent of the absolute pressure values. It reflects arterial stiffness, which transmits mechanical stress into the brain’s small vessels.

How is blood pressure variability different from average blood pressure?

Average blood pressure is what a standard clinic reading captures. Variability refers to how much blood pressure fluctuates moment to moment throughout the day. USC research published in October 2025 found that high short-term variability is independently linked to brain tissue loss in memory and cognition regions, even when average readings appear controlled.

Should older adults aim for the same blood pressure targets as younger people?

Not necessarily. Evidence suggests that very aggressive blood pressure lowering in adults over 80 may reduce cerebral perfusion and worsen cognitive outcomes. Treatment targets should be individualized, particularly for elderly patients with stiffened cerebral vessels.