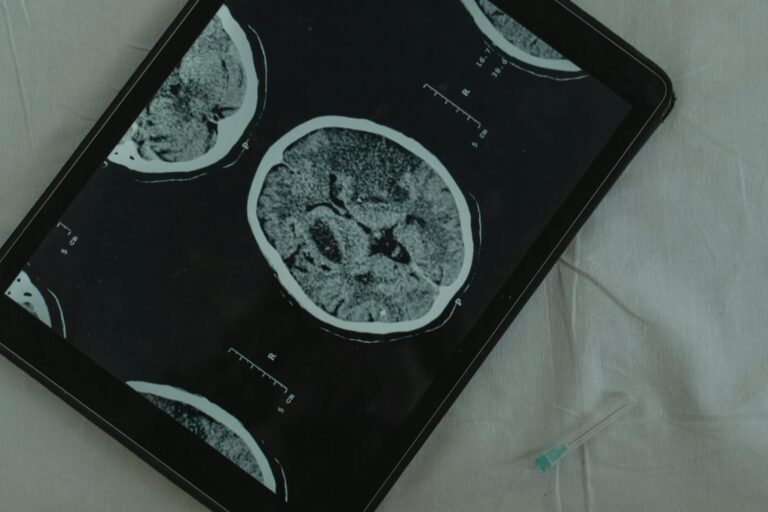

Chronic microvascular ischemic changes refer to cumulative damage in the brain’s small blood vessels that restricts blood flow over time, causing tiny areas of tissue injury. When a radiologist writes this phrase in an MRI report, it means the scan has detected white spots — called white matter hyperintensities or lacunes — scattered throughout the brain’s white matter. These spots mark places where blood supply was insufficient long enough to damage the surrounding tissue.

The condition is essentially another name for cerebral small vessel disease or white matter disease, and it is not one specific illness but a spectrum of changes that can range from a few scattered lesions to widespread involvement. To put it concretely: a 68-year-old woman with a long history of high blood pressure visits her doctor after noticing she is slower to find words and occasionally unsteady on her feet. Her MRI comes back with a note reading “mild chronic microvascular ischemic changes in the periventricular and subcortical white matter.” That report is telling her doctor that years of elevated blood pressure have quietly stressed the small vessels supplying her brain’s deep structures, leaving behind small scars. This article covers what those changes actually represent biologically, how common they are, what symptoms they produce, what drives them, and what can reasonably be done about them.

Table of Contents

- What Does Chronic Microvascular Ischemic Changes Mean on an MRI?

- How Common Are Microvascular Ischemic Changes in the Brain?

- What Symptoms Do Chronic Microvascular Ischemic Changes Cause?

- What Causes Chronic Microvascular Ischemic Changes and Who Is at Risk?

- What Are the Long-Term Risks If Microvascular Ischemic Changes Go Untreated?

- How Is the Severity of Microvascular Ischemic Changes Measured?

- What Does the Future Look Like for People Diagnosed With This Condition?

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Does Chronic Microvascular Ischemic Changes Mean on an MRI?

The word “ischemic” refers to inadequate blood supply — derived from the Greek for “holding back blood.” When the small arteries and arterioles deep inside the brain thicken, stiffen, or narrow due to age, high blood pressure, or other stresses, the tissue they feed receives less oxygen and fewer nutrients. Over months and years, that low-grade deprivation causes patches of the white matter to break down. On an MRI, particularly on T2 and FLAIR sequences, these areas show up as bright white spots. Radiologists call them white matter hyperintensities. When the damage is severe enough to cause a tiny cavity, that cavity is called a lacune.

The term “chronic” is doing important work here. It signals that the changes accumulated gradually rather than from a single event like a major stroke. This is not the kind of brain injury that happens in an hour; it is more like erosion — slow, persistent, and often unnoticed until the cumulative toll becomes significant. The related phrase “small vessel disease” is used interchangeably by many neurologists and radiologists, which can make reading medical literature confusing. Regardless of the label on the report, the underlying story is the same: the brain’s fine vascular network has been under stress, and there is structural evidence of that stress on imaging.

How Common Are Microvascular Ischemic Changes in the Brain?

These changes are remarkably prevalent, and that prevalence increases steeply with age. Roughly 5 percent of people over 50 show significant findings, but by age 60, more than half of adults have some evidence on brain imaging. By the time a person reaches 90, findings are present in virtually everyone. That near-universal prevalence in very old adults reflects the cumulative wear that aging blood vessels sustain over a lifetime, independent of any specific disease. The widespread nature of these findings creates a genuine clinical challenge: not everyone with white matter hyperintensities has symptoms or will develop them.

Up to 95 percent of adults over 60 may show some evidence on imaging, yet a meaningful proportion function without noticeable cognitive impairment. However, the picture changes significantly when the lesion burden is high or when lesions are progressing rapidly. Research from the ARIC study found that patients who showed both white matter hyperintensity grade progression and new lacunes over time faced a substantially elevated long-term stroke risk. Moderate progression occurs in about 60 percent of patients followed over time; severe progression is seen in only about 5 percent, but that smaller group carries disproportionate risk. The warning worth emphasizing here is that a single snapshot mri cannot predict trajectory — serial imaging over time gives far more meaningful information.

What Symptoms Do Chronic Microvascular Ischemic Changes Cause?

This condition is frequently described as a silent disease, and for good reason. Many people who have white matter changes discovered incidentally — during imaging done for an unrelated reason like a headache workup — report no symptoms whatsoever. The brain has considerable redundancy, and early, scattered lesions may not impair any particular function enough to be noticed. This silence is one reason the condition often goes unrecognized until it has been present for years. When symptoms do emerge, they tend to be subtle at first.

Cognitive fog, mild memory difficulties, and slowed processing speed are among the earliest complaints. People often notice they take longer to retrieve names or words, or that they lose their train of thought more easily. Balance and coordination problems can appear, sometimes leading to a characteristic gait that is slow and cautious — sometimes called a “vascular gait.” Headaches, dizziness, and mood changes including depression and irritability are also reported. One symptom that frequently surprises families is urinary urgency or incontinence, which can emerge when lesions affect the frontal lobe’s control over bladder function. In severe or advanced cases, accumulated damage can manifest as frank stroke symptoms: sudden one-sided weakness, vision loss, or acute confusion.

What Causes Chronic Microvascular Ischemic Changes and Who Is at Risk?

Age is the single most powerful risk factor, and no intervention reverses time. But the other risk factors on the list are largely modifiable, which is what gives this diagnosis its clinical importance. High blood pressure is the most significant controllable driver. Blood pressure at or above 140/90 mmHg sustained over years puts persistent mechanical stress on small vessel walls, promoting thickening and narrowing. The relationship is dose-dependent: the higher and longer the blood pressure elevation, the greater the likely lesion burden.

High cholesterol and chronic kidney disease also contribute, likely through overlapping mechanisms involving inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and altered flow dynamics. Obstructive sleep apnea is increasingly recognized as a risk factor; the repeated overnight drops in oxygen saturation stress cerebral vessels in ways that parallel chronic hypertension. Smoking accelerates vascular aging across the entire arterial tree, including the brain’s smallest vessels. The practical tradeoff for anyone newly diagnosed is stark: controlling these risk factors cannot erase existing lesions, but there is reasonable evidence that halting or slowing their progression is achievable. The choice is essentially between aggressive risk factor management now or a higher likelihood of lesion accumulation — and the stroke and dementia risk that comes with it — later.

What Are the Long-Term Risks If Microvascular Ischemic Changes Go Untreated?

The consequences of untreated or advancing small vessel disease are serious. A meta-analysis examining people with white matter lesions found approximately a threefold increased risk of both dementia and stroke compared to people without such findings, along with a roughly doubled risk of death. Chronic microvascular ischemic changes may account for as much as 45 percent of all dementia cases and around 20 percent of strokes — figures that place this condition among the most consequential contributors to both outcomes. The connection to dementia is particularly important for families to understand. White matter damage disrupts the connectivity between different brain regions, even when the regions themselves remain intact.

Think of it as degraded wiring rather than damaged hardware: the processing centers may be functional, but the signals between them travel slowly and unreliably. Over time, this manifests as the slowed thinking, executive dysfunction, and memory difficulty characteristic of vascular cognitive impairment. The critical warning here is that this form of cognitive decline is often mistakenly attributed solely to Alzheimer’s disease. In reality, a significant proportion of dementia in older adults involves a vascular component, and that component is at least partially addressable through the same cardiovascular risk management that protects against heart attack and stroke. Waiting for symptoms to become disabling before acting forfeits much of that opportunity.

How Is the Severity of Microvascular Ischemic Changes Measured?

Radiologists and neurologists use various grading scales to characterize lesion burden on MRI. The Fazekas scale is one of the most widely used, scoring white matter hyperintensities from 0 (none) to 3 (confluent, large areas of involvement) in both periventricular regions and deep white matter. A report describing “Fazekas grade 1” findings indicates punctate, scattered lesions consistent with mild changes — common and often asymptomatic in people over 60.

A “Fazekas grade 3” report, by contrast, describes extensive, merged lesions that carry substantially greater clinical significance. This grading matters because it contextualizes the finding. A mild isolated incidental finding in a cognitively intact 75-year-old warrants monitoring and risk factor review, not alarm. The same finding with rapid progression on follow-up imaging, or in a younger patient with no obvious risk factors, calls for a more thorough workup to identify unusual underlying causes — including inflammatory conditions, genetic disorders like CADASIL, or rare vascular malformations.

What Does the Future Look Like for People Diagnosed With This Condition?

Research in cerebral small vessel disease has accelerated considerably in the past decade, and the trajectory is cautiously encouraging. Neuroimaging techniques are now sensitive enough to detect changes earlier than ever, and there is growing recognition that the vascular contribution to dementia has been underestimated in clinical practice. Several ongoing trials are examining whether aggressive blood pressure control initiated early in the course of white matter disease can meaningfully slow lesion accumulation and preserve cognitive function over years.

For individuals living with this diagnosis today, the most actionable insight from current evidence is that trajectory is not fixed. People who manage hypertension aggressively, address sleep apnea, stop smoking, and maintain physical activity appear to have slower lesion progression than those who do not. The brain’s blood vessels do not regenerate damaged tissue, but the rate of new damage is malleable. Framing this diagnosis not as a verdict but as an early warning — one that identifies elevated risk while there is still time to change the course — is both scientifically grounded and practically useful.

Conclusion

Chronic microvascular ischemic changes mean that the brain’s small blood vessels have sustained cumulative damage that reduces local blood flow and leaves detectable scars in the white matter. The condition is extremely common — present in more than half of adults over 60 — and exists on a spectrum from minor incidental findings to extensive disease carrying tripled stroke and dementia risk. Symptoms range from none at all, to subtle cognitive slowing and balance difficulties, to more severe neurological impairment in advanced cases. The primary drivers are age, high blood pressure, and other cardiovascular risk factors that compound over decades.

The most important takeaway for anyone who has received this finding on an imaging report is that the diagnosis has real clinical meaning and warrants a conversation with a physician about risk factor management. Existing lesions will not disappear, but accumulation of new ones is not inevitable. Blood pressure control in particular appears to be the single most impactful intervention available. Early, sustained attention to cardiovascular health is not just heart protection — it is brain protection, and the evidence that these two things are inseparable has never been stronger.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is chronic microvascular ischemic changes the same as white matter disease?

Yes, essentially. The terms chronic microvascular ischemic changes, white matter disease, and cerebral small vessel disease all describe the same underlying process and are used interchangeably in clinical practice and radiology reports.

Should I be worried if my MRI mentions mild microvascular ischemic changes?

Mild findings are extremely common in people over 60 and often have no clinical significance on their own. That said, the finding is worth discussing with your doctor, particularly to review cardiovascular risk factors like blood pressure and cholesterol that can influence whether changes progress.

Can microvascular ischemic changes be reversed?

No. Existing lesions represent permanent tissue damage and do not resolve. However, the rate of new lesion development can be slowed significantly through aggressive management of risk factors, particularly blood pressure control.

Do these changes always lead to dementia?

Not necessarily. Many people with mild to moderate white matter changes never develop significant cognitive impairment. However, higher lesion burdens and ongoing progression do substantially increase dementia risk — roughly threefold compared to people without these findings.

What kind of doctor should I see for this diagnosis?

A neurologist, particularly one with expertise in cerebrovascular disease or memory disorders, is best positioned to evaluate the clinical significance of the findings in context. Your primary care physician can also manage the cardiovascular risk factors that drive progression.

Is this the same as having a stroke?

Not exactly. Microvascular ischemic changes reflect cumulative small vessel damage rather than a single stroke event. However, some of the small lesions — particularly lacunes — are essentially tiny strokes, and people with significant white matter disease have substantially elevated risk of future stroke.