Coral spawning patterns have captured the attention of Alzheimer’s researchers because these natural phenomena offer unique insights into biological timing, cellular communication, and regeneration processes—areas that are crucial to understanding and potentially treating neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Corals, which are marine animals living in colonies, reproduce through a spectacular event called spawning. This usually happens once a year, often synchronized to specific environmental cues such as the lunar cycle, water temperature, and day length. During spawning, corals release eggs and sperm simultaneously into the water column, creating a massive, coordinated reproductive event. This synchronization is astonishing because it involves millions of individual corals across vast reef systems acting in unison without any central control. The precision and timing of this event fascinate scientists because it reflects a complex biological clock and communication system that operates at multiple levels—from molecular signals within coral cells to environmental cues sensed by the entire reef ecosystem.

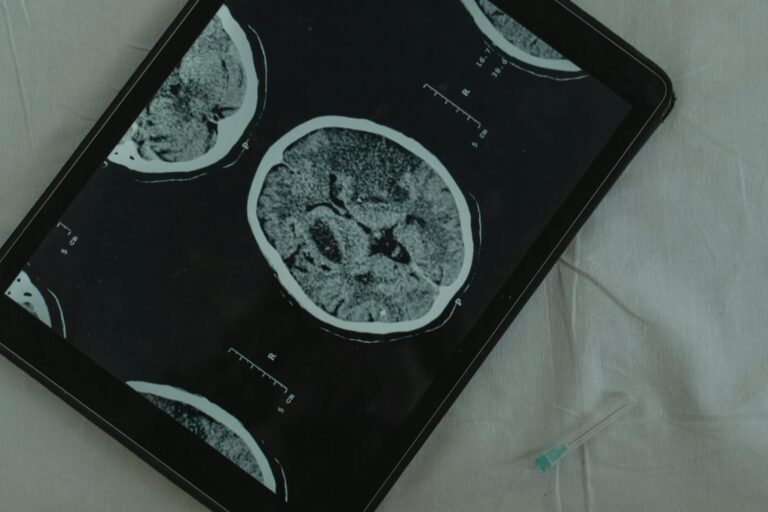

Alzheimer’s disease, on the other hand, is characterized by the progressive loss of neurons and synaptic connections in the brain, leading to memory loss and cognitive decline. One of the biggest challenges in Alzheimer’s research is understanding how to promote brain cell regeneration and restore communication between neurons. The coral spawning phenomenon offers a natural model of how cells can coordinate large-scale, timed events and regenerate new life in a highly organized manner.

One reason coral spawning intrigues Alzheimer’s researchers is the role of cellular signaling pathways that regulate timing and coordination. Corals rely on chemical signals and environmental triggers to synchronize their spawning. These signaling pathways involve molecules that are surprisingly similar to those found in human cells, including those in the brain. By studying how corals use these signals to coordinate spawning, researchers hope to uncover new mechanisms of cellular communication that could be relevant to brain function and repair.

Another aspect is the concept of regeneration. After spawning, coral larvae settle and grow into new coral colonies, effectively regenerating the reef. This natural regeneration process involves stem-cell-like activity and tissue growth, which parallels the goals of Alzheimer’s research to stimulate neural stem cells and promote brain tissue repair. Understanding how corals manage to regenerate complex structures in response to environmental cues could inspire new therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases.

The timing of coral spawning also provides a window into biological clocks, known as circadian and circalunar rhythms. These clocks regulate daily and monthly cycles in many organisms, including humans. Disruptions in circadian rhythms have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease, affecting sleep patterns and cognitive function. Corals’ ability to maintain precise timing for spawning despite environmental variability offers a model for studying how biological clocks can be stabilized or reset, potentially informing treatments that target circadian dysfunction in Alzheimer’s patients.

Furthermore, coral spawning is an example of a highly coordinated community behavior that depends on communication between individual organisms. Alzheimer’s disease involves the breakdown of communication between neurons. By examining how corals maintain communication and coordination at a colony-wide scale, researchers may gain insights into how to preserve or restore neural networks in the human brain.

The simplicity of coral organisms compared to the complexity of the human brain is actually an advantage in research. Corals provide a more accessible system to study fundamental biological processes such as cell signaling, timing, and regeneration without the overwhelming complexity of mammalian brains. Discoveries made in coral biology can then be translated into hypotheses and experiments in neuroscience.

In addition, coral reefs are sensitive indicators of environmental change, and their spawning patterns can be disrupted by stressors such as climate change and pollution. Alzheimer’s researchers are interested in how environmental stress affects biological systems and contributes to disease progression. Studying coral responses to stress during spawning may reveal how cells cope with damage and maintain function, which is relevant to understanding how neurons respond to injury or disease.

The fascination also extends to the genetic level. Advances in genomics have allowed scientists to decode coral genomes and identify genes involved in spawning and regeneration. Some of these genes have counterparts in humans that are implicated in brain development and neurodegeneration. By comparing coral and