For dementia patients dealing with arthritis-related discomfort, a gel-infused memory foam cushion is generally the best starting point. Memory foam distributes body weight evenly across the sitting surface, reducing stress on arthritic shoulders, hips, and the lower back, while a cooling gel layer helps manage the inflammation that makes arthritis pain worse during long periods of seated rest. Products like the ComfiLife Gel Enhanced Seat Cushion, which runs about $35 to $45 and includes a coccyx cutout and non-slip bottom, offer a strong combination of joint relief and practical safety features that matter when someone with cognitive decline is sitting for hours at a time. But choosing the right cushion for this population is more complicated than picking whatever has the best reviews on a shopping site.

Dementia patients are considered one of the most difficult patient groups to seat, according to seating specialists, because of agitation, constant shifting, and elevated fall risk. And the overlap between dementia and arthritis is not a coincidence. Research published in Nature Scientific Reports found that osteoarthritis increases dementia risk by roughly 20 to 33 percent, while a study in the journal Neurology showed rheumatoid arthritis raises dementia risk by approximately 40 percent. These conditions feed each other, and seating that fails to address both pain and skin integrity can accelerate decline. This article covers the specific cushion types that work for this dual diagnosis, the pressure ulcer risks that make cushion selection genuinely urgent, product comparisons with real prices, dementia-specific features you cannot afford to skip, and why the cushion itself is only about a quarter of the total solution.

Table of Contents

- Why Do Dementia Patients With Arthritis Need a Specialized Cushion?

- Memory Foam, Gel, and Air Cells — Which Material Actually Works Best?

- Products Worth Considering and What They Actually Cost

- Dementia-Specific Features You Cannot Afford to Skip

- Why the Cushion Is Only Part of the Answer

- Alternating Air Systems for High-Risk Patients

- Moving Forward With Better Seating Decisions

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Why Do Dementia Patients With Arthritis Need a Specialized Cushion?

The intersection of dementia and arthritis creates a seating problem that standard cushions were never designed to solve. A person with moderate to advanced dementia often cannot tell you they are in pain, cannot reposition themselves when discomfort builds, and may not understand why they feel agitated. Arthritis adds constant joint inflammation to this picture, which means that sitting in a poorly supported position does not just cause temporary soreness — it can trigger behavioral symptoms like restlessness, aggression, and refusal to stay seated that caregivers frequently misattribute to the dementia itself rather than to treatable physical pain. The pressure ulcer risk compounds the problem significantly. A study published in PubMed found that advanced dementia was associated with three times higher odds of developing pressure ulcers (OR = 3.0, 95% CI: 1.4–6.3, P = 0.002).

Meanwhile, CDC data shows that approximately 11 percent of U.S. nursing home residents — about 159,000 people — had pressure ulcers, with Stage 2 being the most common at roughly 50 percent of all cases. Only 35 percent of residents with Stage 2 or higher ulcers received special wound care. When you add arthritis pain that discourages any movement at all, you get a person who sits in one position for hours, bearing weight on the same bony prominences, with skin that is already fragile from age and poor circulation. A specialized cushion needs to do three things simultaneously for this population: relieve pressure across the sitting surface to prevent skin breakdown, support arthritic joints without creating new pressure points, and stay safely in place despite the unpredictable movements of someone with cognitive impairment. A standard throw pillow or even a basic foam pad does none of these adequately.

Memory Foam, Gel, and Air Cells — Which Material Actually Works Best?

Memory foam remains the most widely recommended material for arthritis-related joint pain. Visco-elastic memory foam is recognized for superior pressure relief properties, particularly for individuals with chronic pain, arthritis, or those recovering from injuries. The material conforms to the body’s shape, distributing weight more evenly than static foam and reducing the concentrated stress on hips and the lower back that makes arthritis flare during prolonged sitting. For a dementia patient who sits in a recliner or wheelchair for several hours a day, this conforming support can meaningfully reduce the kind of pain that drives agitation. Gel-infused cushions take the memory foam base and add a cooling gel layer. The temperature regulation is not just a comfort feature — heat buildup worsens inflammation in arthritic joints, and dementia patients who cannot articulate discomfort may simply become increasingly distressed as the seated surface gets warmer.

The Cushion Lab Pressure Relief Seat Cushion, priced around $60 to $70, uses a patented multi-region design that physical therapists frequently recommend, and it addresses both the conforming support and the thermal management issues. However, if the patient is at high risk for pressure ulcers — particularly someone in a wheelchair or specialized seating system who rarely stands or transfers — air cell cushions may be the better choice despite offering less arthritis-specific joint support. ROHO cushions, which use patented interconnected neoprene air cells, have been featured in over 90 clinical studies for healing, treating, and preventing pressure injuries. In clinical comparisons, ROHO cushions produced the lowest average peak pressure among tested cushion types. JAY cushions showed the best average pressure distribution and contact area in static positions, making them particularly effective for the kind of sustained, unmoving sitting that is common in advanced dementia. The tradeoff is that air cell cushions generally do not provide the same contouring joint support as memory foam, so the choice often comes down to whether arthritis pain or pressure ulcer risk is the more immediate danger.

Products Worth Considering and What They Actually Cost

The ComfiLife Gel Enhanced Seat Cushion at $35 to $45 is recommended as the best overall value for combining arthritis comfort with practical features. It pairs a memory foam base with a cooling gel layer, includes a coccyx cutout that relieves tailbone pressure, and has a non-slip rubber bottom. For a dementia patient in a standard armchair or dining chair, this cushion covers the basics at a price point that allows replacing it when incontinence or wear takes a toll. For patients with more significant arthritis pain, particularly in the hips, the Ergo21 LiquiCell Technology cushion is specifically designed for arthritis hip pain and osteoarthritis. The company recommends its travel version for elderly or sensitive individuals under 150 pounds, which is a relevant consideration since many dementia patients in the moderate to advanced stages have lost significant body weight.

The LiquiCell technology uses a fluid-based system that reduces friction and shear forces, which addresses both skin integrity and joint comfort in a way that static foam cannot. The PURAP Liquid and Air Layer Cushion takes a hybrid approach with a combined liquid-air design intended for wheelchair and bed pressure relief. This type of cushion makes more sense for patients who are primarily wheelchair-bound and at elevated pressure ulcer risk. At the higher end, the Cushion Lab Pressure Relief Seat Cushion at $60 to $70 offers the multi-region pressure distribution that therapists tend to favor for patients with specific postural needs. The critical point when comparing these products is that a $35 cushion used correctly and replaced regularly will outperform a $70 cushion that is placed on the wrong surface, never adjusted, and left in use long past its effective lifespan.

Dementia-Specific Features You Cannot Afford to Skip

The single most overlooked feature when buying cushions for dementia patients is a waterproof or water-resistant cover. Incontinence is common in dementia, and a cushion that absorbs urine will degrade rapidly, harbor bacteria, and create skin irritation that compounds the existing pressure ulcer risk. Experts recommend covers with sealed seams or waterfall flap zippers that prevent fluid from reaching the foam or air cells inside. If a cushion does not come with a waterproof cover, an aftermarket incontinence cover should be purchased separately — but verify that the cover does not change the cushion’s pressure distribution properties by adding an unyielding layer between the patient and the cushion surface. Non-slip bottoms and attachment straps are equally critical. A dementia patient who shifts, rocks, or attempts to stand without assistance can easily displace a cushion that is simply placed on a seat surface.

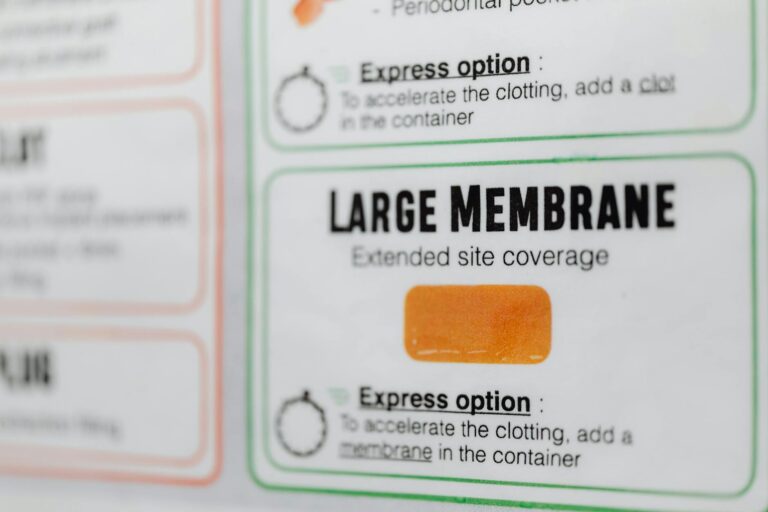

When the cushion slides, the patient either sits on the bare chair surface with no protection or, worse, the displaced cushion creates an uneven surface that increases fall risk. Look for cushions with rubberized bases and, when possible, straps that secure the cushion to the chair frame. This matters less on contoured wheelchair seats where the cushion sits inside a defined space, but it is essential on flat dining chairs, recliners, and armchairs. The tradeoff with waterproof covers is breathability. A fully sealed cover traps heat against the skin, which can worsen both arthritis inflammation and the moisture environment that contributes to skin breakdown. Some higher-end covers use a vapor-permeable waterproof membrane that blocks liquid penetration while allowing air exchange, but these cost more and require more careful laundering to maintain their properties. For most families, a practical compromise is a waterproof cover that gets removed and washed frequently, paired with a gel-infused cushion that provides some thermal management underneath.

Why the Cushion Is Only Part of the Answer

Seating specialists emphasize a point that product marketing consistently underplays: the cushion is only about 25 percent of the solution for pressure management. Proper chair design, positioning technique, and regular movement or repositioning schedules are equally important. A high-quality pressure relief cushion placed on a chair with the wrong seat depth, inadequate armrests, or excessive recline angle will not prevent pressure ulcers or adequately manage arthritis pain, because the patient’s body mechanics are wrong before the cushion surface even becomes relevant. The Alzheimer’s Society in the UK recommends a formal care needs assessment that can include seating and comfort equipment evaluation. More specifically, occupational therapist assessment is recommended before selecting any seating system for a dementia patient.

An OT evaluates the type of seating needed, the patient’s balance and weight-bearing ability, their transfer capacity, and the environment where the chair will be used. Correct positioning benefits digestion, respiratory function, comfort, and pressure relief — all of which are compromised when a well-meaning caregiver simply buys a cushion online and places it on whatever chair the patient happens to use most. The limitation that families run into is access. Not every care setting offers timely OT assessment, and in home care situations, the caregiver may not know that this service exists or is often covered under Medicare or the NHS. If an OT assessment is not immediately available, a reasonable interim approach is a gel-infused memory foam cushion with a waterproof cover and non-slip base, combined with a repositioning schedule of at least every two hours — the same standard used in nursing facilities for pressure ulcer prevention.

Alternating Air Systems for High-Risk Patients

For patients in advanced dementia who are seated for the majority of the day and who have already developed early-stage pressure injuries or are assessed as very high risk, alternating air pressure systems represent the most aggressive cushion intervention available. These powered systems cyclically inflate and deflate different air cells across the cushion surface, continuously shifting the pressure points so that no single area of skin bears sustained load. They are recommended specifically for patients seated for long periods who are at the highest risk of pressure sores. The drawback is complexity.

Alternating air systems require a power source, produce a low-level mechanical hum that may agitate some dementia patients, and need more maintenance than passive cushions. They also do not conform to the body in the same way memory foam does, which means arthritis pain relief is secondary to pressure injury prevention. For a patient whose primary issue is arthritis discomfort rather than active or imminent pressure wounds, an alternating system is likely more intervention than necessary. But for the patient who has both conditions and is spending eight or more hours a day seated with minimal repositioning, the alternating system may be the only option that prevents the kind of deep tissue injury that leads to hospitalization.

Moving Forward With Better Seating Decisions

The understanding of how arthritis and dementia interact is still evolving, but the clinical evidence already points clearly toward integrated care approaches. The finding that osteoarthritis increases dementia risk by 20 to 33 percent and rheumatoid arthritis increases it by roughly 40 percent suggests that managing joint pain effectively is not just a comfort issue — it may influence cognitive trajectory. Seating decisions are part of that management, and they deserve the same clinical attention as medication choices.

As product design improves, expect to see more cushions that combine pressure mapping technology with adaptive materials that respond to both weight distribution and temperature. Some rehabilitation centers already use pressure mapping systems to evaluate cushion performance for individual patients, and as these tools become more accessible, the guesswork in cushion selection should decrease. In the meantime, the practical advice remains straightforward: start with a gel-infused memory foam cushion for moderate needs, escalate to air cell or alternating air systems for high-risk patients, secure an OT assessment when possible, and never treat the cushion as a standalone solution.

Conclusion

Choosing a cushion for a dementia patient with arthritis-related discomfort requires balancing joint pain relief against pressure ulcer prevention, while accounting for the cognitive and behavioral realities of dementia care. Memory foam with cooling gel offers the best combination of arthritis comfort and pressure distribution for most patients, with air cell systems like ROHO or JAY cushions reserved for those at highest risk of skin breakdown. Waterproof covers, non-slip bases, and secure attachment are non-negotiable features for this population.

The most important step a caregiver can take is recognizing that the cushion addresses only about a quarter of the seating problem. An occupational therapist assessment, proper chair selection, correct positioning, and consistent repositioning schedules make up the rest. For families navigating this on their own, a gel-infused memory foam cushion in the $35 to $70 range with a waterproof cover is a reasonable starting point — but it should be the beginning of a seating strategy, not the entirety of one.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I just use a regular pillow or folded blanket instead of a specialized cushion?

No. Regular pillows compress flat within days of sustained use, eliminating any pressure distribution benefit. Folded blankets create uneven surfaces and do not distribute weight across the sitting area. Neither prevents pressure buildup on bony prominences, and neither stays in place during the shifting and movement common in dementia patients. A purpose-built cushion with documented pressure relief properties is a meaningful clinical intervention, not a luxury.

How often should a pressure relief cushion be replaced?

Memory foam cushions typically lose their responsive properties after 12 to 18 months of daily use, though this varies with the patient’s weight and the number of hours spent sitting. A simple test is to press into the cushion and see if it returns to its original shape within a few seconds. If it stays compressed or has developed a permanent body impression, it is no longer providing effective pressure redistribution. Air cell cushions last longer if maintained properly but should be checked regularly for leaks.

My family member keeps pulling the cushion out of the chair. What should I do?

This is common in dementia patients who experience tactile sensitivity or who do not understand the cushion’s purpose. First, ensure the cushion is not causing discomfort — an overly warm or textured cover may be the real issue. Try a cushion with a smooth, cool-touch cover. If the behavior continues, use cushions with chair tie-down straps and consider a cushion that sits inside a contoured seat rather than on top of a flat surface. In some cases, an OT can recommend integrated seating where the cushion is built into the chair design and is not removable.

Is a wheelchair cushion different from a seat cushion for a regular chair?

Yes. Wheelchair cushions are designed for a defined seat pan with specific width and depth dimensions, and they account for the fact that the user may spend many continuous hours seated with limited ability to reposition. They tend to prioritize pressure distribution and skin protection over comfort. A seat cushion for a dining chair or recliner is typically less specialized and assumes the user will stand, shift, or change positions more frequently. A dementia patient who uses both a wheelchair and a regular chair may need different cushions for each.

Does insurance cover pressure relief cushions for dementia patients?

In many cases, yes. In the United States, Medicare Part B may cover seat cushions classified as durable medical equipment when prescribed by a physician and deemed medically necessary. In the UK, the Alzheimer’s Society recommends a formal care needs assessment that can include seating and comfort equipment. Coverage varies significantly by plan, region, and clinical documentation, so request a prescription from the patient’s physician and check with the specific insurer before purchasing.