Dementia with Lewy bodies typically progresses through seven broad stages, beginning with subtle behavioral shifts like increased anxiety and sleep disturbance, advancing through mild cognitive impairment and worsening motor symptoms, and ultimately reaching an end stage where the person is bedridden and unable to speak or swallow independently. The full course from early symptoms to death spans an average of five to seven years after diagnosis, though some people decline rapidly within months while others live a decade or longer. What makes DLB progression particularly disorienting for families is its signature unpredictability — a person might carry on a sharp conversation one afternoon and be completely confused by evening, a pattern of fluctuation that persists across every stage of the disease.

DLB is the second most common form of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease, affecting approximately 1.4 million people in the United States and accounting for roughly 5 percent of all dementia cases in older adults. It strikes most often between ages 50 and 85 and is more common in men than women. This article walks through each stage of progression in detail, explains the four core clinical features that distinguish DLB from other dementias, examines what the research says about life expectancy, and offers practical guidance for caregivers facing each phase of the disease.

Table of Contents

- How Does Dementia with Lewy Bodies Progress Through Each Stage?

- The Four Core Features That Shape DLB’s Unpredictable Course

- What the Research Says About Life Expectancy After Diagnosis

- How Caregiving Demands Shift at Each Stage of DLB

- Why DLB Is Frequently Misdiagnosed and What That Means for Progression

- The Significance of Fluctuating Cognition in Day-to-Day Life

- What Current Research Offers and Where Gaps Remain

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Does Dementia with Lewy Bodies Progress Through Each Stage?

Clinicians and caregiving organizations generally describe DLB progression using a seven-stage framework, though it is important to understand that these stages are not rigid checkpoints — they bleed into each other, and the fluctuating nature of the disease means a person can appear to be in one stage during a good stretch and a later stage during a bad one. Stage 1 involves no obvious dementia symptoms, but subtle changes are often visible in hindsight: increased anxiety or depression, disrupted sleep, a slight tremor, or mild muscle stiffness that a primary care doctor might attribute to aging or stress. Stage 2 brings mild cognitive impairment — the person starts having noticeable trouble with recall, following complex conversations, or solving problems that used to come easily. By Stage 3, those cognitive and motor issues begin interfering with daily tasks like managing finances, cooking, or driving, and visual hallucinations may appear for the first time. Stage 4 is often the point of formal diagnosis, which tells you something important about how DLB typically gets identified: by the time most people receive a diagnosis, the disease has already been progressing for years. At this stage, hallucinations become more frequent and vivid, daily functioning is visibly impaired, and the combination of cognitive and movement symptoms becomes difficult to attribute to anything else.

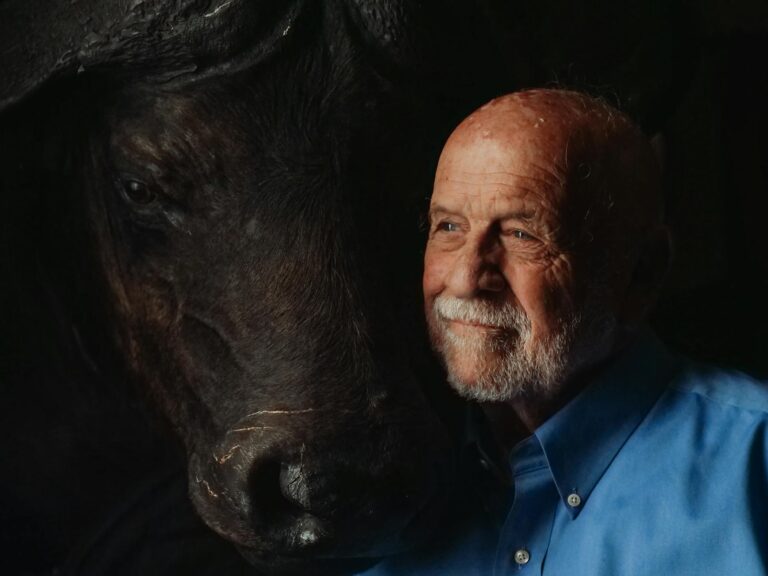

Consider a 72-year-old man who has been seeing a neurologist for what was thought to be early Parkinson’s disease — when detailed visual hallucinations and significant cognitive fluctuations emerge alongside his movement problems, the clinical picture shifts toward DLB. This delayed recognition is one of the most common frustrations families report. Stages 5 through 7 represent the severe and end-stage phases. In Stage 5, the person begins forgetting names of close family members and becomes confused about people, places, and time. Stage 6 brings severe memory loss — the person may no longer recognize a spouse or children — along with significant behavioral changes. Stage 7, the final phase, typically lasts 1.5 to 2.5 years and is characterized by loss of speech, inability to sit up independently, difficulty swallowing, and the need for full-time care. Most people are bedridden during this stage.

The Four Core Features That Shape DLB’s Unpredictable Course

The 2017 Fourth Consensus Report of the DLB Consortium identified four core clinical features that define the disease and distinguish it from Alzheimer’s and other dementias. The first and most characteristic is fluctuating cognition — periods of alertness and coherence alternating with confusion and unresponsiveness, sometimes shifting over the course of hours but more typically cycling over days to weeks. This is what makes DLB uniquely disorienting for caregivers. A wife might describe her husband as “completely himself” on Tuesday and “like a different person” by Thursday, with no obvious trigger for the change. Unlike the more linear, gradual decline seen in Alzheimer’s disease, DLB’s fluctuations can make it seem as though the person is improving, which can lead families to question the diagnosis or delay planning for future care needs. The second core feature is recurrent visual hallucinations, which are typically detailed and realistic — not vague shadows, but clear images of people, children, or animals that the person may interact with or describe in vivid detail. These hallucinations occur in the majority of DLB patients and often appear early in the disease course.

The third feature, REM sleep behavior disorder, deserves particular attention because it can appear years or even decades before any other DLB symptom. People with RBD lose the normal muscle paralysis that occurs during REM sleep, causing them to physically act out dreams — punching, kicking, shouting, or falling out of bed. A person diagnosed with isolated RBD in their fifties may not develop cognitive symptoms until their seventies, but the sleep disorder was the earliest sign of the underlying Lewy body pathology all along. The fourth core feature is parkinsonism: hunched posture, rigid muscles, a shuffling gait, and slowed movement. However, not every person with DLB will develop all four features, and they rarely appear all at once. Some people present primarily with cognitive symptoms and hallucinations while experiencing only mild motor problems. Others may have pronounced parkinsonism that initially leads to a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis before cognitive decline shifts the picture toward DLB. This variability means that if someone you love has been diagnosed with DLB but does not have hallucinations or obvious movement problems, the diagnosis is not necessarily wrong — the full constellation of symptoms may emerge at different points along the progression.

What the Research Says About Life Expectancy After Diagnosis

The honest answer about DLB life expectancy is that the range is enormous, which makes individual predictions nearly impossible. The commonly cited figure is an average survival of five to seven years after diagnosis, but a 2019 meta-analysis found the average was closer to 4.1 years post-diagnosis — approximately 1.6 years shorter than what is typically seen in Alzheimer’s disease. One in five patients — 20 percent — die within two years of diagnosis. In a survey of 658 respondents connected to people with DLB, more than 10 percent died within one year of diagnosis, while another 10 percent survived more than seven years, and some lived more than a decade. What accounts for this enormous range? Key mortality risk factors include male sex, older age at the time of onset, a higher burden of other medical conditions like heart disease or diabetes, and greater functional impairment at the time of diagnosis.

A 60-year-old woman diagnosed at an early stage with few other health problems has a fundamentally different trajectory than an 80-year-old man diagnosed at a moderate stage with cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The stage at which someone is diagnosed also matters significantly — because many people are not formally diagnosed until Stage 4, the “years after diagnosis” figure understates the total duration of the disease. Someone whose DLB was caught at Stage 2 through a sleep disorder clinic identifying RBD will appear to have a longer post-diagnosis survival than someone whose DLB was identified only after hallucinations and significant cognitive decline forced the issue. DLB also leads to higher rates of disability, hospitalization, and institutionalization compared to Alzheimer’s disease, with lower quality of life and increased care costs. This is partly because the disease attacks on multiple fronts simultaneously — cognition, movement, sleep, autonomic function — creating a caregiving burden that is broader and more complex than what most families associate with “dementia.”.

How Caregiving Demands Shift at Each Stage of DLB

In the early stages, the primary caregiving challenge is often not physical but emotional and logistical. The person with DLB may resist the idea that anything is wrong, especially during good periods when their cognition seems relatively intact. Practical priorities during Stages 1 through 3 include establishing legal and financial plans while the person can still participate in decision-making, finding a neurologist experienced with Lewy body dementias specifically, and beginning to document the pattern of fluctuations and symptoms for medical appointments. One common mistake families make during this period is assuming the good days mean the diagnosis is wrong and delaying preparation for what lies ahead. The middle stages — roughly Stages 4 and 5 — bring a shift toward hands-on daily assistance. The person may need help with bathing, dressing, and meal preparation. Hallucinations may become a source of distress or, in some cases, relative calm — some people with DLB are not frightened by their hallucinations and may even find them comforting, while others become agitated and fearful.

The caregiving tradeoff during this period often involves balancing safety against autonomy. Removing a person’s ability to move freely through the house reduces fall risk but may increase agitation and confusion. Installing motion-sensor nightlights and removing trip hazards is a less restrictive approach than physical barriers, but it will not prevent all falls given the movement difficulties inherent in parkinsonism. By Stages 6 and 7, caregiving becomes a full-time, physically demanding job. Many families face the difficult decision of whether to continue home care or transition to a skilled nursing facility. Neither option is without significant downsides — home care preserves familiarity but can exhaust caregivers to the point of their own health crises, while facility care provides professional support but the unfamiliar environment can worsen confusion and agitation in someone with DLB. There is no universally right answer, and the decision often comes down to the specific resources, health, and support network available to the family.

Why DLB Is Frequently Misdiagnosed and What That Means for Progression

One of the most consequential problems in DLB care is that the disease is frequently misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, or a psychiatric condition. When movement symptoms dominate the early picture, a Parkinson’s diagnosis is common. When cognitive symptoms come first, Alzheimer’s is the usual assumption. When hallucinations appear before significant cognitive decline, some clinicians pursue psychiatric explanations. Each misdiagnosis carries real risks for disease management — certain medications commonly prescribed for other conditions can be dangerous in DLB. The most critical medication warning involves traditional antipsychotic medications like haloperidol. People with DLB have a severe sensitivity to these drugs, and administration can cause life-threatening neuroleptic malignant syndrome, dramatic worsening of parkinsonism, or sudden changes in consciousness. Even some newer atypical antipsychotics carry risk.

This is not a theoretical concern — it is one of the most important clinical facts about DLB and a primary reason accurate diagnosis matters. If a person is misdiagnosed with a psychiatric condition and prescribed a traditional antipsychotic for their hallucinations, the consequences can be catastrophic. Families should ensure that every healthcare provider involved in their loved one’s care, including emergency room doctors who may not have access to the full medical history, knows about the DLB diagnosis. As of 2025, no disease-modifying treatment exists for DLB. All current treatments are symptomatic — cholinesterase inhibitors like donepezil may help with cognitive symptoms and hallucinations, carbidopa-levodopa may improve movement problems, and melatonin or clonazepam can address REM sleep behavior disorder. However, the tradeoffs between these treatments require careful management, because medications that improve one set of symptoms can sometimes worsen another. Increasing dopamine medication to help with movement may intensify hallucinations, for example. This balancing act is a persistent challenge throughout the disease course.

The Significance of Fluctuating Cognition in Day-to-Day Life

Fluctuating cognition is often the single most confusing aspect of DLB for families and, frankly, for some clinicians as well. A study published in the journal Neurology found that detectable clinical change in DLB can occur over as little as six months, but the daily and weekly fluctuations can make it difficult to assess whether the person’s overall baseline has actually shifted. A daughter visiting her father every Sunday might see him lucid and conversational three weeks in a row, then arrive to find him unable to follow a simple sentence — and this variability is the disease itself, not a sign that something new has gone wrong.

This pattern has practical implications for medical appointments, cognitive testing, and care planning. If a neurologist sees the person on a good day, test scores may not reflect the severity of impairment the family observes at home. Keeping a written log of daily functioning — even brief notes about alertness, confusion episodes, falls, and hallucination frequency — can provide clinicians with a much more accurate picture than a single office visit. It also helps families themselves track whether the overall trajectory is declining, stable, or in one of the temporary better stretches that DLB sometimes allows.

What Current Research Offers and Where Gaps Remain

The DLB research landscape has expanded significantly in recent years, but it remains far behind Alzheimer’s disease in terms of funding, clinical trials, and public awareness. The identification of REM sleep behavior disorder as a potential early biomarker for Lewy body pathology has opened a window for studying people at risk for DLB years or decades before cognitive symptoms appear, which could eventually enable earlier intervention if disease-modifying therapies are developed.

Several clinical trials are exploring treatments that target alpha-synuclein, the protein that forms the Lewy bodies responsible for the disease, though none have yet demonstrated efficacy in large-scale human trials. For families living with DLB now, the most meaningful advances are likely to come in symptomatic management and care coordination rather than a cure in the near term. Improved diagnostic tools, greater clinician awareness of DLB’s distinct features, and better training for caregivers on managing fluctuations and medication sensitivities are all areas where progress can meaningfully improve quality of life even in the absence of a breakthrough treatment.

Conclusion

Dementia with Lewy bodies follows a broadly predictable seven-stage progression from subtle behavioral changes to end-stage dependence, but its course is defined by the unpredictability within that framework — fluctuating cognition, the interplay of cognitive and motor symptoms, and enormous variation in how quickly different individuals decline. Average survival after diagnosis runs approximately five to seven years, though some people live much longer and others decline rapidly.

The four core features — fluctuating cognition, visual hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder, and parkinsonism — distinguish DLB from other dementias and have direct implications for treatment and safety. For caregivers, the most important steps are securing an accurate diagnosis from a neurologist experienced with Lewy body dementias, ensuring all medical providers are aware of the DLB diagnosis and its medication sensitivities, planning legal and financial matters early while the person can still participate, and building a support network that can sustain the long and demanding caregiving journey ahead. The Lewy Body Dementia Association at lbda.org is a reliable starting point for connecting with resources and other families navigating the same path.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is dementia with Lewy bodies the same as Parkinson’s disease dementia?

They are closely related — both involve Lewy body pathology — but they are classified as separate conditions. The general clinical convention is that if cognitive symptoms appear first or within a year of movement symptoms, the diagnosis is DLB. If a person has had Parkinson’s disease for years before developing dementia, the diagnosis is Parkinson’s disease dementia. In practice, the two conditions overlap substantially, and some researchers consider them part of a single disease spectrum.

How quickly does DLB progress compared to Alzheimer’s disease?

On average, DLB progresses somewhat faster. A 2019 meta-analysis found average post-diagnosis survival of 4.1 years for DLB, approximately 1.6 years shorter than Alzheimer’s. However, individual variation is large — some people with DLB live more than 10 years after diagnosis, while 20 percent die within 2 years.

Can REM sleep behavior disorder predict DLB before other symptoms appear?

Yes. RBD can appear years or even decades before cognitive or motor symptoms of DLB emerge. Not everyone with RBD will develop DLB — some develop Parkinson’s disease or multiple system atrophy instead — but isolated RBD is now recognized as one of the strongest early markers of underlying Lewy body pathology.

Why do people with DLB have good days and bad days?

Fluctuating cognition is one of the four core features of DLB and is thought to result from the way Lewy bodies disrupt neurotransmitter systems in the brain, particularly acetylcholine. The fluctuations are not caused by external factors like poor sleep or stress, although those can worsen them. This pattern of variability distinguishes DLB from the more steady decline typically seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

Are there medications that should be avoided with DLB?

Yes. Traditional antipsychotic medications such as haloperidol are particularly dangerous and can cause severe, potentially fatal reactions in people with DLB. Even some newer atypical antipsychotics carry elevated risk. Any medication that blocks dopamine should be used with extreme caution. Families should make sure every healthcare provider — including emergency departments — is aware of the DLB diagnosis.

What is the end stage of DLB like?

Stage 7, the final phase, typically lasts 1.5 to 2.5 years. The person loses the ability to speak, cannot sit up independently, and has difficulty swallowing, which increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Most people are bedridden and require full-time care. Decisions about feeding tubes, hospice enrollment, and comfort care measures usually arise during this stage.