The Global Deterioration Scale, commonly known as the GDS or the Reisberg Scale, is a seven-stage clinical framework used to measure the severity of cognitive decline in people with primary degenerative dementia, most often Alzheimer’s disease. Developed by Dr. Barry Reisberg, it gives clinicians a structured way to characterize where a patient currently sits on the spectrum from completely normal cognition to end-stage dementia.

Rather than producing a numerical test score, a clinician reads through the stage descriptions and uses judgment to determine which stage best matches what they observe in the patient. For example, a person who occasionally forgets names of acquaintances but otherwise functions independently would likely be placed at Stage 2, whereas someone who can no longer dress or bathe without help and has lost the ability to speak more than a few words would be placed at Stage 6 or 7. The GDS is widely used in clinical practice, research, and long-term care planning because it tracks not just memory loss but the broader picture of cognitive and functional decline across time. This article covers how the scale is structured, what each stage means in practical terms, how clinicians apply it, its strengths and limitations, and how it compares to a related tool called the FAST.

Table of Contents

- What Is the GDS Scale and How Does It Measure Dementia Severity?

- How Do Clinicians Actually Apply the GDS in Practice?

- What Each Stage Looks Like in Real Life

- How the GDS Helps with Care Planning and Prognosis

- Limitations of the GDS That Clinicians and Families Should Know

- Who Developed the GDS and Why It Became a Standard Tool

- The GDS in Modern Dementia Care and Research

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the GDS Scale and How Does It Measure Dementia Severity?

The Global Deterioration Scale organizes cognitive decline into seven distinct stages. Stages 1 through 3 are considered pre-dementia phases, meaning the person either has no impairment or has deficits that do not yet meet the clinical threshold for a dementia diagnosis. Stages 4 through 7 represent true dementia, progressing from mild to very severe. This division matters practically because it shapes what kinds of interventions, conversations, and planning are appropriate at each point. Stage 1 is defined as no cognitive decline — a person functioning normally for their age. Stage 2 represents very mild decline, the kind of forgetfulness that can overlap with normal aging, such as misplacing keys or struggling to recall a word.

Stage 3 is mild cognitive decline, where deficits become noticeable to close family members and the person themselves: getting lost in a familiar area, reading a passage and retaining little of it, or showing measurable difficulty on cognitive testing. At this stage, a formal dementia diagnosis is not yet warranted, but it is a signal worth monitoring carefully. Stage 4 marks the beginning of what the GDS calls dementia proper — moderate cognitive decline, equivalent to early or mild dementia. The person may have difficulty managing finances, planning a complex meal, or recalling major recent events. By Stage 5, they need assistance with day-to-day tasks like choosing appropriate clothing, though they can usually still eat and use the toilet independently. Stage 6 involves severe decline, with near-total dependence for personal care and often significant behavioral changes. Stage 7, the most severe, describes very late-stage dementia in which the person may lose the ability to speak, walk, or swallow.

How Do Clinicians Actually Apply the GDS in Practice?

One important detail that surprises many families is that the GDS does not work like a test with a calculated score. There is no series of right-or-wrong answers that gets totaled and mapped to a stage. Instead, the clinician reads through the criteria for each of the seven stages and applies their professional judgment to decide which description best fits the patient they are evaluating. This is what researchers call a clinician-rated scale, and its accuracy depends on the experience and thoroughness of the person doing the assessment. Interrater reliability — the degree to which different clinicians evaluating the same patient arrive at the same stage — ranges from 0.82 to 0.92 across multiple studies. That range represents good reliability for a clinical judgment tool, but it is not perfect.

Two experienced clinicians might occasionally place a patient at Stage 4 versus Stage 5, particularly when a person sits right on the boundary between stages. This is one limitation of the GDS that users should understand: it is a staging tool, not a precise measurement instrument. Borderline cases are genuinely ambiguous. The GDS is typically used in combination with other assessments rather than in isolation. A comprehensive evaluation might include the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), neuropsychological testing, caregiver interviews, and the GDS together. The GDS adds something the cognitive tests alone cannot fully capture: a sense of the whole disease trajectory, including functional ability and behavioral changes, not just what the person can recall or calculate on a given day.

What Each Stage Looks Like in Real Life

Understanding the stages in abstract clinical language is one thing. Seeing what they look like in a real household is another. At Stage 3, a family might notice that their parent, who was always sharp about finances, is now making small errors on bills and has started double-checking tasks they would never have second-guessed before. The person themselves often knows something is off, which can cause anxiety and avoidance. A doctor may tell the family the diagnosis is not yet dementia, which is technically accurate but can feel unsatisfying when the changes are clearly real. Stage 4 tends to be when families first hear the word dementia from a physician. The person can no longer manage complex tasks independently.

Planning a holiday gathering or navigating a new route in the car becomes genuinely difficult. Finances deteriorate. Long-term memories, however, may remain vivid — someone at Stage 4 might describe their childhood in detail while having no memory of last week’s dinner. By Stage 6 and 7, the disease has fundamentally altered every aspect of daily life. In Stage 6, a person may not recognize their spouse or children and may experience episodes of agitation, wandering, or delusions. Stage 7 is characterized by a near-complete loss of voluntary function: speech reduces to single words or none, swallowing becomes impaired, and the person is largely bedridden. For families navigating these stages, the GDS can serve as a roadmap that helps them understand that what they are witnessing, however devastating, is a predictable pattern of disease progression.

How the GDS Helps with Care Planning and Prognosis

One of the most practical uses of the GDS is setting appropriate care expectations at each stage. When a geriatric care manager or social worker knows a patient is at Stage 5, they can advise the family to begin thinking about in-home aides, discuss medication management strategies, and introduce the possibility that residential memory care may eventually be needed. The scale gives everyone — clinicians, families, insurers — a shared vocabulary for describing where the person is and where they are likely headed. The GDS is also used in hospice eligibility determinations. Medicare hospice guidelines for dementia typically look at functional markers consistent with Stage 7 GDS, such as the inability to walk without assistance, loss of meaningful verbal communication, and incontinence. This is where the GDS intersects with the FAST — the Functional Assessment Staging Tool, also developed by Dr.

Reisberg — which breaks down the later stages of dementia into finer sub-stages based on functional abilities. FAST Stage 7 has specific sub-stages (7a through 7f) that map to increasingly severe functional losses. Hospice teams often use FAST alongside GDS because it provides that additional granularity in the period when detailed functional tracking matters most. The tradeoff between the two tools is precision versus simplicity. The GDS is easier to apply across a wide range of clinical settings and is more appropriate for tracking a patient from the earliest signs of forgetfulness through the full disease course. The FAST is more detailed but more specialized, and it is most useful in the later stages of dementia where functional distinctions matter for care decisions. Neither tool replaces the other; they are complementary.

Limitations of the GDS That Clinicians and Families Should Know

The GDS was designed primarily with Alzheimer’s disease in mind. It tracks the typical pattern of Alzheimer’s, which tends to begin with memory loss and progress through language, orientation, and physical function in a relatively predictable sequence. For other types of dementia, the fit can be imperfect. Frontotemporal dementia, for example, often begins with personality and behavioral changes rather than memory loss, which means a person with frontotemporal dementia might appear deceptively high-functioning on some GDS criteria while showing profound impairment in judgment or social behavior that the scale does not adequately capture at early stages. Vascular dementia, which results from strokes or reduced blood flow to the brain, can progress in an uneven, stepwise pattern rather than the gradual linear decline that the GDS assumes.

A person might remain stable for months and then show sudden significant deterioration following another vascular event. The GDS stages are less cleanly applicable in these cases, and clinicians should be transparent with families when the dementia type does not follow the typical trajectory. There is also a cultural and linguistic dimension to keep in mind. Several GDS criteria involve assessing whether someone can perform complex tasks or follow current events — abilities that vary significantly based on education level, occupation, and cultural background. A person who never managed household finances or read a newspaper regularly might appear to be at a lower stage than they actually are, or vice versa. Good clinical practice involves accounting for these factors when making staging judgments, but the scale itself does not provide explicit guidance for doing so.

Who Developed the GDS and Why It Became a Standard Tool

Dr. Barry Reisberg introduced the Global Deterioration Scale in a 1982 publication in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which has since been widely cited in the clinical and research literature.

His goal was to create a practical staging system that clinicians could use to communicate meaningfully about disease severity and to track progression across time, including in clinical trials testing potential treatments. The scale gained traction quickly because it addressed a real gap: before standardized staging tools, clinicians lacked a shared language for comparing patients or describing disease course in a consistent way. The GDS gave Alzheimer’s research a common reference point and became a standard feature of clinical practice in memory care settings across the United States and internationally.

The GDS in Modern Dementia Care and Research

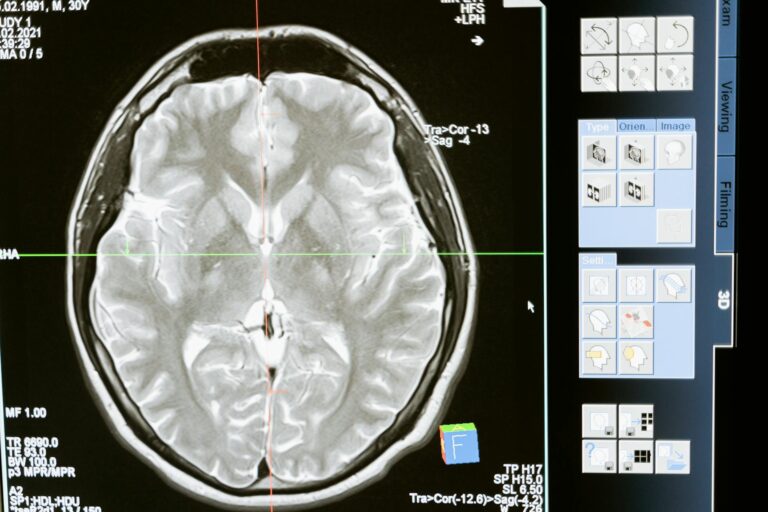

Decades after its introduction, the GDS remains a standard tool in memory clinics, geriatric practices, hospice organizations, and dementia research studies. It has been validated across multiple languages and adapted for use in diverse populations. As biomarker testing — including amyloid PET scans and cerebrospinal fluid analysis — becomes more common in Alzheimer’s diagnosis, researchers are working to understand how biological markers correspond to GDS stages, with the goal of identifying disease progression even before clinical symptoms appear.

The emergence of new staging frameworks, such as the 2024 revised Alzheimer’s disease biological staging criteria proposed by the Alzheimer’s Association, reflects ongoing debate about how best to characterize disease progression in the era of precision medicine. These biological stages do not replace the GDS for clinical practice — where observable symptoms and function guide care decisions — but they signal that the field is evolving. The GDS will likely continue to serve its original purpose: helping clinicians and families understand where a person is in their journey and plan accordingly.

Conclusion

The Global Deterioration Scale is a seven-stage clinical framework that gives clinicians, families, and care teams a structured way to assess and communicate the severity of cognitive decline in primary degenerative dementia. Developed by Dr. Barry Reisberg, it spans from Stage 1 (no decline) through Stage 7 (very severe decline), with Stages 1 through 3 representing pre-dementia phases and Stages 4 through 7 representing the dementia continuum.

It is applied not by calculating a test score but through informed clinical judgment, and it carries good interrater reliability across studies. For families caring for a loved one with dementia, understanding the GDS can help make sense of disease progression and what to expect at each phase. For clinicians, it remains a foundational tool for tracking change over time and triggering appropriate care conversations — from early planning at Stage 3 to hospice evaluation at Stage 7. When used alongside complementary tools like the FAST, and interpreted in the context of the individual’s dementia type, background, and circumstances, the GDS is one of the most useful frameworks available for navigating a difficult and complex disease.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a higher GDS stage always worse?

Yes. The stages progress from 1 (no impairment) to 7 (very severe decline). A higher stage number means greater cognitive and functional loss.

Can someone move backward to a lower GDS stage?

No. The GDS is designed to track a progressive disease. While some medications may slow progression or temporarily stabilize function, the scale does not account for meaningful improvement. A person who appears to improve substantially should be reassessed to determine whether the original staging was accurate.

At what GDS stage is someone considered to have dementia?

Stages 4 through 7 are dementia stages. Stages 1 through 3 — including Stage 3, which involves noticeable cognitive deficits — are considered pre-dementia phases.

How often should the GDS be reassessed?

There is no universal rule, but reassessment is typically done when a clinician or family notices meaningful change in cognition or function, or at regular intervals in a care plan. In research settings, reassessments are often scheduled every 6 to 12 months.

What is the difference between the GDS and the MMSE?

The MMSE (Mini-Mental State Examination) is a cognitive test that produces a numerical score based on the person’s performance. The GDS is a staging tool based on clinical observation of symptoms and function over time, not performance on a test in the moment. The two tools measure different things and are often used together.

Is the GDS used to diagnose dementia?

No. The GDS measures severity and stages a condition once it is already suspected or diagnosed. A formal dementia diagnosis requires a comprehensive clinical evaluation including medical history, cognitive testing, and often imaging — not the GDS alone.