Rapidly progressive dementia is a syndrome in which significant cognitive decline occurs over weeks to months rather than the years-long trajectory most people associate with conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. Where a typical Alzheimer’s patient might experience a gradual slide over eight to twelve years, someone with rapidly progressive dementia can go from independent functioning to severe impairment in under a year, sometimes in as little as a few weeks. A classic example is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a prion disorder that can take a person from their first memory lapses to a bedridden state within four to six months.

What makes rapidly progressive dementia distinct is not just speed but also what it signals. The fast pace often points to causes that differ sharply from the usual neurodegenerative suspects, including infections, autoimmune inflammation, cancers, toxic exposures, and metabolic emergencies. Some of these causes are treatable and even reversible if caught early, which is why recognizing the rapid timeline matters so much. This article covers the major causes of rapidly progressive dementia, how doctors work through the diagnostic process, which conditions can be reversed, and what families should know when they find themselves in the middle of a frightening and fast-moving decline.

Table of Contents

- What Exactly Qualifies as Rapidly Progressive Dementia and How Is It Defined?

- The Major Causes Behind Rapidly Progressive Dementia

- How Doctors Work Through the Diagnostic Process

- Which Forms of Rapidly Progressive Dementia Can Be Treated or Reversed?

- Why Rapidly Progressive Alzheimer’s Disease Creates Diagnostic Confusion

- The Emotional and Practical Impact on Families

- Research Directions and What May Change in the Coming Years

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Exactly Qualifies as Rapidly Progressive Dementia and How Is It Defined?

There is no single agreed-upon cutoff, but most specialists define rapidly progressive dementia as a significant decline in cognition that develops over less than one to two years, with many cases progressing within just weeks or months. The key distinction is pace. Standard Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and Lewy body dementia typically unfold across several years, giving families time to adjust and plan. Rapidly progressive dementia compresses that entire trajectory into a fraction of the time, often catching everyone off guard. Neurologists sometimes use the term to describe any dementia that reaches a moderate or severe stage within twelve months of symptom onset. In clinical practice, the threshold for concern is even shorter.

If a patient goes from normal to noticeably impaired in under six months, most specialists will pursue an aggressive workup. For comparison, a person with typical Alzheimer’s might score a 24 out of 30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination at diagnosis and take three to four years to drop below 15. A person with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease might make that same decline in three months. It is worth noting that sometimes a slowly progressive dementia can appear rapid. A family may not notice early changes until something dramatic happens, like a hospitalization or a move to a new environment, at which point the deficits seem to arrive all at once. Part of the diagnostic work involves distinguishing a genuinely fast onset from a slow disease that simply went unrecognized. This matters because the treatment paths are completely different.

The Major Causes Behind Rapidly Progressive Dementia

The list of conditions that can cause rapid cognitive decline is long, which is both daunting and, in a certain sense, hopeful. Prion diseases like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease are the most feared and most iconic cause. These disorders involve misfolded proteins that spread through brain tissue, causing sponge-like damage. Sporadic CJD accounts for roughly 85 percent of cases, strikes without warning, and has no effective treatment. However, prion disease is rare, affecting roughly one to two people per million each year. Autoimmune encephalitis has emerged as one of the most important diagnoses in this category, largely because it is treatable.

Conditions like anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis can cause hallucinations, seizures, and rapid cognitive collapse in previously healthy people, including young adults. When identified and treated with immunotherapy, many patients recover substantially. The challenge is that autoimmune encephalitis can mimic psychiatric illness early on, and if a clinician is not thinking about it, the window for effective treatment can close. Other causes include central nervous system infections such as HIV-associated dementia, neurosyphilis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and viral encephalitis. Cancers can drive rapid decline either through direct brain metastases or through paraneoplastic syndromes, where the immune system attacks brain tissue in response to a tumor elsewhere in the body. Toxic and metabolic causes round out the list: Wernicke encephalopathy from thiamine deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy from liver failure, and heavy metal poisoning can all produce fast-moving cognitive deterioration. However, if the underlying metabolic problem has persisted too long before treatment, the damage may not be fully reversible even after correction.

How Doctors Work Through the Diagnostic Process

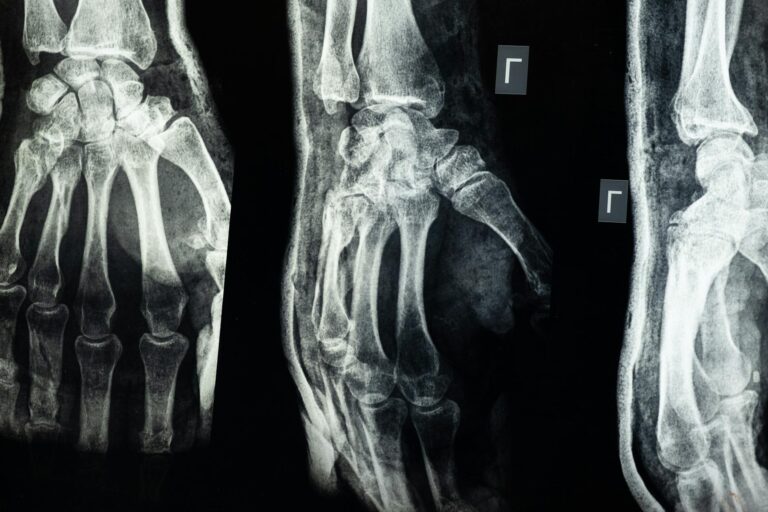

When a patient presents with rapid cognitive decline, the evaluation is urgent and methodical. Neurologists typically start with blood work looking for metabolic derangements, vitamin deficiencies, thyroid dysfunction, inflammatory markers, and infectious disease screening. A brain MRI with specific sequences is essential. In Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, diffusion-weighted imaging often shows a characteristic pattern of restricted diffusion in the cortex and basal ganglia, a finding so distinctive that an experienced neuroradiologist can suspect the diagnosis from the scan alone. Lumbar puncture is a critical step. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis can detect infections, inflammation, and specific biomarkers. The 14-3-3 protein and real-time quaking-induced conversion assay for prion disease, antibody panels for autoimmune encephalitis, and cytology for cancerous cells in the spinal fluid all come from this single procedure.

An electroencephalogram is also standard and may reveal periodic sharp wave complexes in CJD or patterns suggestive of seizure activity that might be driving the decline. A concrete example helps illustrate the process. A 58-year-old woman develops confusion, difficulty speaking, and involuntary muscle jerks over four weeks. Her MRI shows cortical ribboning on diffusion-weighted imaging. Her spinal fluid tests positive on the RT-QuIC prion assay. The EEG shows periodic discharges. The diagnosis of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is made with high confidence. In contrast, a 32-year-old man with a similar pace of decline but a different MRI pattern, inflammatory spinal fluid, and positive NMDA receptor antibodies would receive a completely different diagnosis and, critically, a treatable one.

Which Forms of Rapidly Progressive Dementia Can Be Treated or Reversed?

The most important clinical question in any case of rapidly progressive dementia is whether the cause is reversible. Studies examining referrals to specialized prion disease centers have found that somewhere between 20 and 30 percent of patients initially suspected of having CJD turn out to have a different, sometimes treatable diagnosis. That number is significant. It means that roughly one in four to one in five patients in this category may have a condition that responds to treatment. Autoimmune encephalitis leads the list of treatable causes. Early immunotherapy with corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasma exchange can halt and even reverse the damage in many cases. Infectious causes respond to appropriate antimicrobials when identified in time. Neurosyphilis, for instance, is treated with intravenous penicillin, and patients can recover meaningful function.

Metabolic causes like thiamine deficiency or hypothyroidism respond to supplementation and correction. The tradeoff in all of these is time. The longer the brain is under assault before treatment starts, the less recovery is possible. Prion diseases, unfortunately, remain in the untreatable column. No medication has been shown to slow or stop the progression of CJD. The same is largely true for rapidly progressive variants of Alzheimer’s disease, which do exist and can occasionally mimic the timeline of prion disease. Familial CJD and genetic prion diseases carry the additional burden of implications for family members, who may face decisions about predictive genetic testing. The gap between the treatable and untreatable causes is why the diagnostic workup needs to be fast and thorough. Missing an autoimmune encephalitis because you assumed prion disease is a tragedy that can be prevented.

Why Rapidly Progressive Alzheimer’s Disease Creates Diagnostic Confusion

Most people think of Alzheimer’s as the slow, steady form of dementia, but a subset of Alzheimer’s patients experience an unusually rapid course. Studies have shown that roughly 10 to 30 percent of autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s cases had a rapid clinical progression, reaching severe dementia within three to four years of onset. In some cases, the decline is fast enough to raise concern for prion disease, leading to a full CJD workup. This overlap creates real clinical difficulty. A rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s case may show some of the same features as CJD, including myoclonus, or involuntary muscle jerks, and certain EEG changes. The MRI may be ambiguous.

Biomarkers help, but no single test draws a clean line. Researchers have identified some factors associated with a faster Alzheimer’s trajectory, including higher levels of certain inflammatory markers, specific genetic profiles, and the presence of co-existing Lewy body or vascular pathology. However, there is no way to predict at diagnosis exactly how fast any individual Alzheimer’s case will progress. Families dealing with rapid Alzheimer’s face a particular kind of grief. They are given a diagnosis that most people associate with a slow decline, but their experience is anything but slow. Support resources designed around a multi-year caregiving arc may feel irrelevant when the timeline is compressed to a year or two. This is an area where the dementia care community has been slow to adapt, and families often report feeling isolated by a trajectory that does not match what they read online or hear from support groups.

The Emotional and Practical Impact on Families

The speed of rapidly progressive dementia leaves families with almost no time to adjust. In typical dementia, there may be months or years of mild symptoms during which families can research care options, get legal and financial affairs in order, and gradually shift into a caregiving role. With rapidly progressive dementia, these steps must happen simultaneously with a crisis-level medical workup. One week you are driving your spouse to a neurology appointment; two weeks later, you may be arranging hospice care.

A real-world scenario captures the difficulty. A family notices that their 65-year-old father is confused and unsteady. Within three weeks, he cannot feed himself. The family is navigating brain MRIs, spinal taps, and specialist consultations while also trying to understand power of attorney documents they never thought they would need so soon. Palliative care teams and social workers who specialize in rapidly progressive conditions can be invaluable in these situations, but access varies widely depending on geography and hospital resources.

Research Directions and What May Change in the Coming Years

Prion disease has long been considered a dead end for treatment, but recent research has given cautious reasons for attention. Antisense oligonucleotide therapy, which targets the genetic instructions for prion protein production, has entered clinical trials for genetic forms of prion disease. If effective, it would represent the first disease-modifying treatment for any prion disorder. Meanwhile, autoimmune encephalitis research continues to identify new antibody targets, expanding the number of patients who can receive specific diagnosis and treatment.

Improved biomarker panels and faster laboratory turnaround times are also reshaping the diagnostic process. Where the RT-QuIC prion assay once took weeks, many centers now return results in days. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease, including plasma phospho-tau, may help clinicians quickly distinguish a rapid Alzheimer’s case from a prion or autoimmune cause without waiting for a full cerebrospinal fluid workup. The goal across the field is to shrink the time between symptom onset and accurate diagnosis, because in rapidly progressive dementia, every week of diagnostic delay matters.

Conclusion

Rapidly progressive dementia is defined by its timeline, with meaningful cognitive decline occurring over weeks to months instead of years. The speed is alarming, but it also serves as a clinical signal that the cause may not be a typical neurodegenerative disease. Prion diseases like CJD are the most well-known cause, but autoimmune encephalitis, infections, cancers, and metabolic disorders account for a substantial share of cases, and many of these are treatable if caught early.

The diagnostic workup is urgent and involves imaging, spinal fluid analysis, blood work, and EEG, all aimed at answering one critical question: is this reversible? For families, the most important step is to push for rapid evaluation at a center with experience in these conditions. If a loved one is declining fast, do not accept a wait-and-see approach. Ask for referral to a neurologist who handles rapidly progressive dementia, and make sure the workup includes testing for autoimmune and infectious causes alongside prion biomarkers. Time is the one resource you cannot get back, and in this particular corner of dementia care, acting quickly can mean the difference between a treatable illness and a missed opportunity.

Frequently Asked Questions

How fast does Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease typically progress?

Sporadic CJD usually progresses from first symptoms to severe dementia within three to six months, with most patients dying within a year of onset. Some variant forms may progress slightly more slowly, but CJD is consistently one of the fastest dementias known.

Can rapidly progressive dementia be cured?

It depends entirely on the cause. Autoimmune encephalitis, certain infections, and metabolic disturbances can often be treated and sometimes fully reversed. Prion diseases and rapid Alzheimer’s variants currently have no cure. This is why thorough diagnostic testing is critical.

What is the difference between rapidly progressive dementia and delirium?

Delirium is an acute state of confusion that typically fluctuates over hours to days and is caused by a medical illness, medication, or infection. It is usually reversible once the trigger is treated. Rapidly progressive dementia involves sustained cognitive decline over weeks to months and reflects structural or progressive brain damage. However, delirium can occur on top of dementia, making the picture more complicated.

Should our family get genetic testing after a prion disease diagnosis?

About 10 to 15 percent of prion disease cases are genetic, caused by mutations in the PRNP gene. If genetic CJD is confirmed or suspected, family members may be offered genetic counseling and optional testing. This is a deeply personal decision with no single right answer, and a genetic counselor can help weigh the implications.

Is rapidly progressive dementia hereditary?

Most cases are not. Sporadic CJD arises without any known genetic cause, and autoimmune or infectious causes are not inherited. However, familial prion diseases and certain genetic forms of early-onset Alzheimer’s can run in families. A detailed family history is part of the standard evaluation.