During late-stage Alzheimer’s disease, the brain has undergone such catastrophic structural damage that it can no longer support even the most basic human functions. Massive neuronal death has shrunk the brain significantly — Alzheimer’s patients lose brain volume at a rate of 1 to 3 percent per year, compared to roughly 0.5 percent in normal aging. By the final stage, the destruction has spread from the memory centers deep in the temporal lobes outward to regions that control swallowing, walking, and breathing. The person who once forgot names and misplaced keys is now unable to communicate, recognize loved ones, or move independently. It is, in the starkest medical terms, a brain that is being consumed from the inside out by rogue proteins, runaway inflammation, and the wholesale collapse of its chemical messaging systems. This devastation is not sudden.

It is the endpoint of a process that began years — sometimes decades — before diagnosis, with the quiet accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles in a small region called the entorhinal cortex. But by late-stage disease, the damage is no longer localized. It is everywhere. Today, approximately 7.2 million Americans aged 65 and older are living with Alzheimer’s dementia, about 1 in 9 people in that age group. Deaths from Alzheimer’s have increased more than 142 percent between 2000 and 2022, even as deaths from heart disease, stroke, and HIV declined. Understanding what is physically happening inside the brain during these final stages matters — not just for researchers chasing treatments, but for families trying to make sense of why the person they love has changed so profoundly. This article walks through the specific mechanisms of late-stage brain destruction: the structural shrinkage and regional spread of atrophy, the protein pathology that drives it, the collapse of the brain’s chemical communication system, the role of chronic inflammation, and what all of this means in practical terms for patients and their caregivers.

Table of Contents

- What Physically Happens to the Brain’s Structure in Late-Stage Alzheimer’s?

- How Amyloid Plaques and Tau Tangles Destroy Neurons From Two Directions

- The Collapse of the Brain’s Chemical Messaging System

- How Neuroinflammation Accelerates the Damage

- When the Brain Can No Longer Support Basic Bodily Functions

- The Scale of the Crisis by the Numbers

- What Emerging Research Tells Us About the Future

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Physically Happens to the Brain’s Structure in Late-Stage Alzheimer’s?

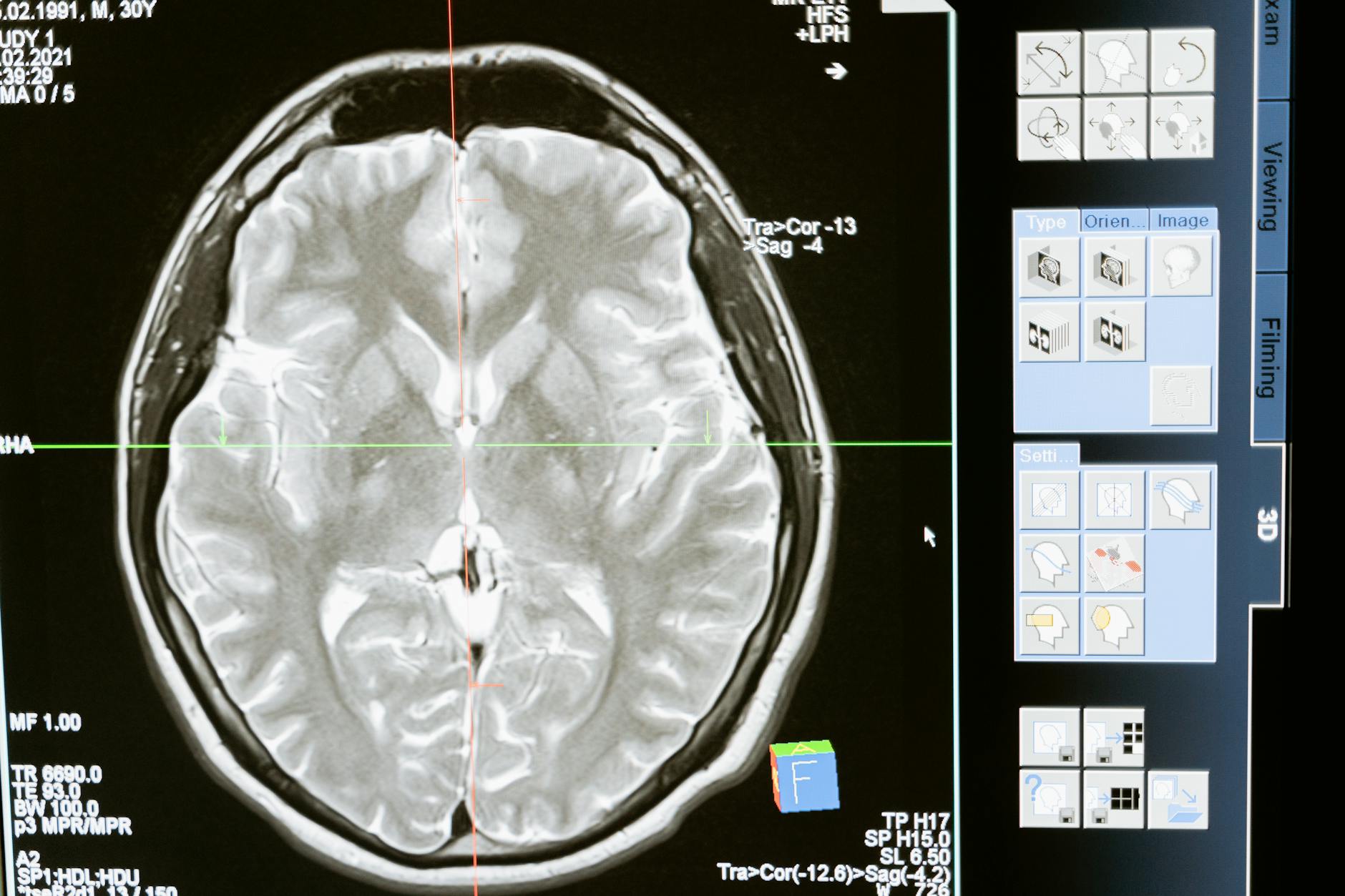

The most visible change in a late-stage Alzheimer’s brain is its sheer size — or rather, the lack of it. If you placed an MRI scan of a healthy brain next to one from a person in late-stage Alzheimer’s, the difference would be immediately obvious even to an untrained eye. The sulci, the grooves that run along the brain’s surface, are dramatically widened. The ventricles, the fluid-filled cavities deep inside the brain, are vastly enlarged, ballooning into space that was once occupied by living neurons. This is the visible signature of widespread neuronal death. The shrinkage follows a predictable geographic pattern. Research has shown that atrophy begins in the medial temporal lobes, including the hippocampus and the fusiform gyrus, at least three years before a clinical diagnosis is made.

From there, the damage spreads to the posterior temporal and parietal lobes — regions critical for language, spatial awareness, and integrating sensory information. Eventually, the frontal lobes are overtaken, eroding executive function, personality, and the ability to plan even the simplest actions. To put this in perspective, a healthy 75-year-old’s brain is slowly losing neurons as part of normal aging, but the rate is roughly a fifth of what an Alzheimer’s patient experiences. By the time the disease reaches its final stage, the brain may have lost a third or more of its total mass. The hippocampus deserves special attention because it is ground zero for the disease’s assault on memory. This seahorse-shaped structure deep in the temporal lobe is where new memories are encoded before being sent to other regions for long-term storage. In patients progressing toward clinical Alzheimer’s, hippocampal atrophy rates accelerate by approximately 0.22 percent per year squared — a compounding loss that explains why memory decline does not happen in a straight line but instead curves sharply downward. By late-stage disease, the hippocampus is so severely damaged that new memory formation is essentially impossible, and even deeply encoded old memories begin to fragment and disappear.

How Amyloid Plaques and Tau Tangles Destroy Neurons From Two Directions

The structural devastation described above is driven by two rogue proteins that attack the brain from opposite sides of the cell membrane. Outside neurons, dense deposits of amyloid-beta peptide clump together into insoluble plaques. Inside neurons, hyperphosphorylated tau protein twists into neurofibrillary tangles that choke the cell’s internal transport system. Together, these two pathologies form the hallmark signature of Alzheimer’s disease, and by the late stage, they have colonized nearly every region of the cortex. Amyloid plaques begin accumulating years before symptoms appear, initially clustering in the default mode network — brain regions active during rest and self-referential thought. As the disease progresses, plaques spread across all cortical regions. But amyloid alone does not tell the whole story. Many older adults have significant amyloid deposits yet remain cognitively sharp. It is the tau tangles that correlate most closely with actual neuronal death and cognitive decline.

Tau normally stabilizes microtubules, the structural scaffolding inside neurons that transports nutrients and signaling molecules from the cell body to the synapses. When tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, it detaches from the microtubules and aggregates into tangles. The transport system collapses, synapses starve, and the neuron dies. Tangles spread in a stereotypical pattern — from the entorhinal cortex to the hippocampus and then outward through the cortex — and this spread tracks closely with the progression of symptoms. However, there is a complication that makes the pathology even more damaging. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, or CAA, often accompanies plaques and tangles. In CAA, amyloid-beta deposits build up in the walls of blood vessels in the brain, weakening them and sometimes causing microbleeds. This vascular damage compounds the neurodegenerative damage, reducing blood flow to already-struggling brain regions and potentially accelerating decline. For families, this means that even when Alzheimer’s is the primary diagnosis, the brain is often fighting a two-front war — one against protein aggregation and one against vascular deterioration.

The Collapse of the Brain’s Chemical Messaging System

One of the most functionally devastating changes in late-stage Alzheimer’s is the near-total destruction of the cholinergic system, the brain’s primary network for producing acetylcholine. This neurotransmitter is essential for attention, learning, and memory. The main production facility is a cluster of neurons in the basal forebrain called the nucleus basalis of Meynert, and by late-stage Alzheimer’s, 70 to 80 percent of these cholinergic neurons have died. The downstream effect is severe. Choline acetyltransferase, or ChAT, the enzyme responsible for synthesizing acetylcholine, shows activity reductions of 50 to 85 percent in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Without adequate acetylcholine, the surviving neurons cannot communicate effectively, even if they are still structurally intact. It is analogous to a telephone network where the wires are still in place but the electrical current has been cut — the infrastructure exists, but no signals are getting through.

This is one reason why late-stage patients may have moments of apparent alertness or recognition but cannot sustain them. The hardware is degraded, but the software is essentially unpowered. An important nuance that researchers have clarified is that this cholinergic collapse is specifically a late-stage event. In the early and mild stages of Alzheimer’s, there is measurable loss of cholinergic function — synapses are weakened and acetylcholine signaling is impaired — but the neurons themselves are still largely alive. This distinction matters because the medications commonly prescribed for Alzheimer’s, cholinesterase inhibitors like donepezil, work by preventing the breakdown of whatever acetylcholine is still being produced. In early stages, when enough neurons survive to produce some acetylcholine, these drugs can offer modest benefits. By late-stage disease, when the neurons themselves are dead, there is simply not enough acetylcholine left for these drugs to preserve. This is the hard biological reality behind why current Alzheimer’s medications lose their effectiveness as the disease progresses.

How Neuroinflammation Accelerates the Damage

The brain has its own immune system, and in late-stage Alzheimer’s, that system has gone haywire. Microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, and astrocytes, the star-shaped support cells that normally nourish neurons and maintain the blood-brain barrier, become chronically activated. Instead of clearing debris and protecting neurons, they begin releasing a sustained flood of inflammatory molecules, cytokines, and reactive oxygen species that damage surrounding tissue. In a healthy brain, microglia respond to threats by briefly activating, neutralizing the problem, and returning to a resting state. In Alzheimer’s, the constant presence of amyloid plaques and dying neurons keeps microglia permanently switched on. This chronic neuroinflammation creates a vicious cycle: inflammation damages neurons, damaged neurons release more debris, and the debris triggers more inflammation. Researchers at Yale identified a distinct amyloid-beta oligomer subtype, designated ACU193-positive, found inside neurons and on nearby reactive astrocytes.

This oligomer subtype may act as an early instigator of the inflammatory cascade, potentially explaining why inflammation becomes self-sustaining rather than self-limiting. The tradeoff for any future therapeutic approach is delicate. Completely suppressing the brain’s immune response would leave it vulnerable to infection and unable to clear normal cellular waste. But allowing inflammation to rage unchecked accelerates neuronal death. Anti-inflammatory strategies in Alzheimer’s research have repeatedly stumbled on this balance — broad immunosuppression has not worked in clinical trials, and more targeted approaches are still in early stages. For families, the practical takeaway is that the brain damage visible in late-stage Alzheimer’s is not caused solely by plaques and tangles. Inflammation is an active, ongoing contributor to the destruction, which is one reason why decline can sometimes seem to accelerate unexpectedly.

When the Brain Can No Longer Support Basic Bodily Functions

Perhaps the most difficult reality of late-stage Alzheimer’s for caregivers is watching the disease move beyond cognition and begin dismantling the brain’s control over the body itself. In earlier stages, the damage is concentrated in the cortex — the outer layer responsible for thought, language, and memory. But as neuronal death spreads inward and downward, it reaches the brainstem and the motor control regions that govern swallowing, posture, bladder control, and eventually breathing. Difficulty swallowing, known as dysphagia, is one of the most dangerous late-stage complications. When the neural pathways coordinating the muscles of the throat and esophagus degrade, food and liquid can be aspirated into the lungs, leading to aspiration pneumonia — the most common immediate cause of death in Alzheimer’s patients.

Similarly, the loss of motor control leads to immobility, which brings its own cascade of medical risks: pressure ulcers, blood clots, and muscle contractures. The neural networks that once coordinated walking, turning in bed, or even coughing have broken down entirely. A critical warning for families and caregivers: the loss of these basic functions does not follow a smooth, predictable timeline. A patient may retain the ability to swallow safely for months and then lose it rapidly over a period of weeks. This unpredictability is rooted in the biology — the brain regions controlling autonomic and motor functions are not all equally vulnerable, and the pattern of neuronal death varies from patient to patient. Care plans should be reassessed frequently rather than set on a fixed schedule, and any sudden change in swallowing ability, mobility, or responsiveness warrants immediate medical evaluation.

The Scale of the Crisis by the Numbers

The statistics paint a stark picture of where Alzheimer’s stands as a public health challenge. As of the most recent data, 7.2 million Americans aged 65 and older are living with Alzheimer’s dementia. In 2022, 120,122 deaths were attributed to the disease, making it the seventh leading cause of death in the United States. Without a medical breakthrough, projections estimate that the number of affected Americans will reach 13.8 million by 2060.

What makes these numbers particularly alarming is the trend line. Between 2000 and 2022, deaths from Alzheimer’s increased by more than 142 percent. During the same period, deaths from heart disease, stroke, and HIV all decreased — a testament to successful research investment and public health campaigns for those conditions. Alzheimer’s is moving in the opposite direction, and the aging of the Baby Boomer generation means the patient population will grow substantially in the coming decades regardless of any near-term therapeutic advances.

What Emerging Research Tells Us About the Future

The past few years have brought genuine, if modest, progress. The identification of specific amyloid-beta oligomer subtypes like the ACU193-positive form found by Yale researchers offers new potential drug targets that are more precise than the broad anti-amyloid approach of earlier clinical trials. Advances in brain imaging and biomarker detection now allow researchers to identify Alzheimer’s pathology years before symptoms appear, opening a window for intervention that did not previously exist. But it is important to be clear-eyed about the gap between research progress and clinical reality. No current treatment can halt or reverse the neuronal death that defines late-stage disease.

The cholinergic neurons are gone. The cortical tissue is gone. The tangles have spread throughout the brain. For patients already in the late stage, the focus remains on comfort, dignity, and quality of life. The real promise of emerging research lies in the possibility of intervening much earlier — catching the disease during the long, silent phase when plaques and tangles are accumulating but the brain’s compensatory mechanisms are still intact. Whether that promise will be realized, and how quickly, remains genuinely uncertain.

Conclusion

Late-stage Alzheimer’s disease represents one of the most complete and devastating forms of brain destruction in all of medicine. The combination of widespread structural atrophy, toxic protein accumulation, cholinergic system collapse, chronic neuroinflammation, and eventual loss of basic motor and autonomic functions leaves patients entirely dependent on others. Every major system in the brain — from the molecular transport within individual neurons to the large-scale networks connecting brain regions — is compromised or destroyed. For families navigating this stage, understanding the biology can provide a measure of clarity in an otherwise overwhelming experience.

The personality changes, the loss of recognition, the inability to swallow or walk — these are not mysterious or random. They are the direct, predictable consequences of specific types of brain damage occurring in specific locations. That knowledge does not make the experience less painful, but it can inform better care decisions, more realistic expectations, and a deeper compassion for what the person with Alzheimer’s is going through. If you are caring for someone in late-stage Alzheimer’s, work closely with a palliative care team, reassess the care plan frequently, and do not hesitate to ask for help.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does the late stage of Alzheimer’s typically last?

Late-stage Alzheimer’s can last from several weeks to several years, but the average is roughly one to three years. The duration varies significantly depending on the patient’s overall health, age at onset, and quality of care. Because late-stage patients are vulnerable to complications like aspiration pneumonia and infections, the timeline is highly individual.

Can a person in late-stage Alzheimer’s still feel pain or emotions?

Yes. Even when patients can no longer communicate verbally or recognize caregivers, the brain regions that process basic sensory input and emotional responses may still retain some function. Facial grimacing, agitation, and changes in breathing can all indicate pain or distress. Caregivers should never assume that a non-verbal patient is not experiencing discomfort.

Why do Alzheimer’s medications stop working in the late stage?

The most commonly prescribed Alzheimer’s drugs, cholinesterase inhibitors, work by preserving the acetylcholine that surviving cholinergic neurons still produce. By late-stage disease, 70 to 80 percent of these neurons in the basal forebrain have died. There is simply not enough acetylcholine being produced for the drugs to have a meaningful effect.

Is late-stage Alzheimer’s the actual cause of death, or do patients die from complications?

In most cases, the immediate cause of death is a complication rather than the disease itself. Aspiration pneumonia is the most common, occurring when the brain can no longer coordinate the swallowing reflex and food or liquid enters the lungs. However, Alzheimer’s is considered the underlying cause of death because the neurological damage is what makes the patient vulnerable to these fatal complications.

Does late-stage brain damage ever reverse or stabilize?

No. The neuronal death that characterizes late-stage Alzheimer’s is irreversible with current medical technology. Neurons in the adult brain have very limited regenerative capacity, and the scale of cell loss in late-stage disease is far beyond what the brain could compensate for. Research into earlier intervention aims to prevent reaching this stage, but there is currently no way to restore brain tissue once it has been destroyed.