Several interconnected factors can accelerate dementia progression, and many of them are modifiable. Cardiovascular problems like uncontrolled high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol damage the brain’s blood vessels over time, starving neurons of oxygen and speeding cognitive decline. Social isolation, physical inactivity, untreated depression, poor sleep, and certain medications — particularly anticholinergics and benzodiazepines — can all push the disease forward faster than it would otherwise move. A person diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer’s at 72 who also has poorly managed type 2 diabetes and lives alone, for instance, may progress to moderate-stage dementia years earlier than someone of the same age whose blood sugar is well controlled and who stays socially engaged. Understanding which factors matter most is not just academic.

It changes how families plan care, how doctors adjust treatment, and how the person living with dementia can preserve independence for as long as possible. This article breaks down the major accelerators of dementia progression, from vascular health and medication risks to sleep disruption and caregiver decisions, and explains where the evidence is strongest and where it remains uncertain. Not every factor carries equal weight, and some interact with each other in ways researchers are still untangling. But the practical takeaway is that even after a diagnosis, the speed of decline is not entirely predetermined. What follows is a detailed look at the factors that matter most and what can realistically be done about them.

Table of Contents

- Which Medical Conditions Speed Up Dementia Progression the Most?

- How Medications Can Quietly Accelerate Cognitive Decline

- The Role of Social Isolation and Depression in Faster Decline

- How Physical Inactivity and Poor Nutrition Compound Dementia

- Sleep Disruption as a Hidden Driver of Faster Progression

- How Repeated Hospitalizations and Delirium Cause Step-Down Declines

- Emerging Research on Inflammation and Gut Health

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Which Medical Conditions Speed Up Dementia Progression the Most?

Cardiovascular disease stands at the top of the list. Research published in The Lancet Neurology has consistently shown that people with Alzheimer’s who also have vascular risk factors — hypertension, atherosclerosis, atrial fibrillation, or a history of stroke — experience faster cognitive decline than those without these conditions. The mechanism is straightforward: the brain consumes roughly 20 percent of the body’s oxygen supply, and anything that restricts blood flow compounds the damage that dementia is already causing. A 2019 study from Rush University found that older adults with even small areas of vascular damage in the brain had measurably faster memory loss, regardless of their amyloid plaque burden. Diabetes is a particularly potent accelerator.

Chronically elevated blood sugar damages small blood vessels throughout the brain and promotes inflammation, both of which worsen neurodegeneration. A large Swedish study tracking over 2,800 people with dementia found that those with diabetes progressed from mild to severe stages an average of 1.5 to 2 years faster than those without it. Insulin resistance may also directly interfere with the brain’s ability to clear toxic amyloid protein, creating a vicious cycle. Kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart failure also appear to hasten decline, though the evidence for each is less robust than for diabetes and hypertension. The common thread is oxygen deprivation and systemic inflammation. For families, the practical implication is that aggressive management of these conditions — not just the dementia itself — is one of the most effective ways to slow progression.

How Medications Can Quietly Accelerate Cognitive Decline

Certain prescription and over-the-counter medications have anticholinergic properties, meaning they block acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter already depleted in Alzheimer’s disease. Common culprits include diphenhydramine (Benadryl), oxybutynin for bladder control, older tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline, and first-generation antihistamines. A landmark 2015 study from the University of Washington found that cumulative anticholinergic use over several years was associated with a significantly higher risk of dementia, and for those already diagnosed, these drugs can accelerate the trajectory noticeably. Benzodiazepines — medications like lorazepam, diazepam, and alprazolam prescribed for anxiety and sleep — are another concern. While they do not cause dementia in the traditional sense, they impair memory consolidation, increase fall risk, and can create a fog that mimics or worsens dementia symptoms.

In a person whose cognitive reserve is already compromised, the added burden of a sedating medication can push them past functional thresholds faster. However, stopping these medications abruptly is dangerous. Benzodiazepine withdrawal can cause seizures, and suddenly discontinuing a bladder medication can cause severe discomfort and dignity issues. The right approach involves a careful, supervised taper with the prescribing doctor, ideally with a geriatric pharmacist involved. Families should not take it upon themselves to remove medications without medical guidance, even when the rationale for doing so seems clear.

The Role of Social Isolation and Depression in Faster Decline

Loneliness is not just emotionally painful — it is a measurable risk factor for faster dementia progression. A 2020 study in the Journal of Alzheimer’s disease found that socially isolated older adults experienced cognitive decline at roughly twice the rate of those with regular social contact. The brain is a use-it-or-lose-it organ, and social interaction provides some of the most complex cognitive stimulation available: reading facial expressions, following conversational threads, recalling shared memories, and managing emotional responses all require significant neural activity. Depression frequently co-occurs with dementia and accelerates its course. Estimates suggest that 30 to 50 percent of people with Alzheimer’s also experience clinically significant depression, and when it goes untreated, cognitive and functional decline accelerates.

Depression reduces motivation to eat well, exercise, take medications, and engage socially — all of which compound the problem. A person with early-stage dementia who withdraws to their bedroom, stops calling friends, and loses interest in food is often experiencing depression, not simply “the disease progressing,” and treating the depression can meaningfully slow the decline. The challenge is that depression in dementia is easy to miss. The person may not articulate sadness; instead, they may become more irritable, refuse activities they once enjoyed, or sleep excessively. Standard depression screening tools often fail in this population because the symptoms overlap so heavily with dementia itself. Families and care providers who notice a sudden acceleration in decline should consider depression as a treatable contributor rather than assuming the disease has simply entered a new phase.

How Physical Inactivity and Poor Nutrition Compound Dementia

Exercise is one of the few interventions with consistent evidence for slowing cognitive decline after a dementia diagnosis. A 2018 Cochrane review found that regular aerobic exercise — even moderate walking — was associated with modest but real improvements in daily functioning for people with mild to moderate dementia. The benefits likely come from improved cerebral blood flow, reduced inflammation, and increased production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, a protein that supports neuron survival. A 150-minute weekly walking routine will not reverse the disease, but it may preserve the ability to dress independently or follow a conversation for months longer. Malnutrition is a stealth accelerator that receives far too little attention. As dementia progresses, people often lose interest in food, forget to eat, struggle with swallowing, or develop altered taste perception.

Weight loss in dementia is strongly correlated with faster decline and higher mortality. A study in the Journal of the American Medical Directors Association found that people with Alzheimer’s who lost more than 5 percent of their body weight over six months had significantly faster functional decline than those who maintained their weight. The tradeoff with exercise is practical: pushing a person with moderate dementia to exercise when they are frightened, confused, or physically frail can cause falls, agitation, and resistance that damages the caregiving relationship. The goal should be appropriate movement — seated exercises, garden walks, dancing to familiar music — rather than rigorous fitness programs designed for healthy older adults. Nutrition interventions face a similar tension: forcing someone to eat when they genuinely cannot swallow safely creates aspiration risk. The right balance requires ongoing reassessment as the disease evolves.

Sleep Disruption as a Hidden Driver of Faster Progression

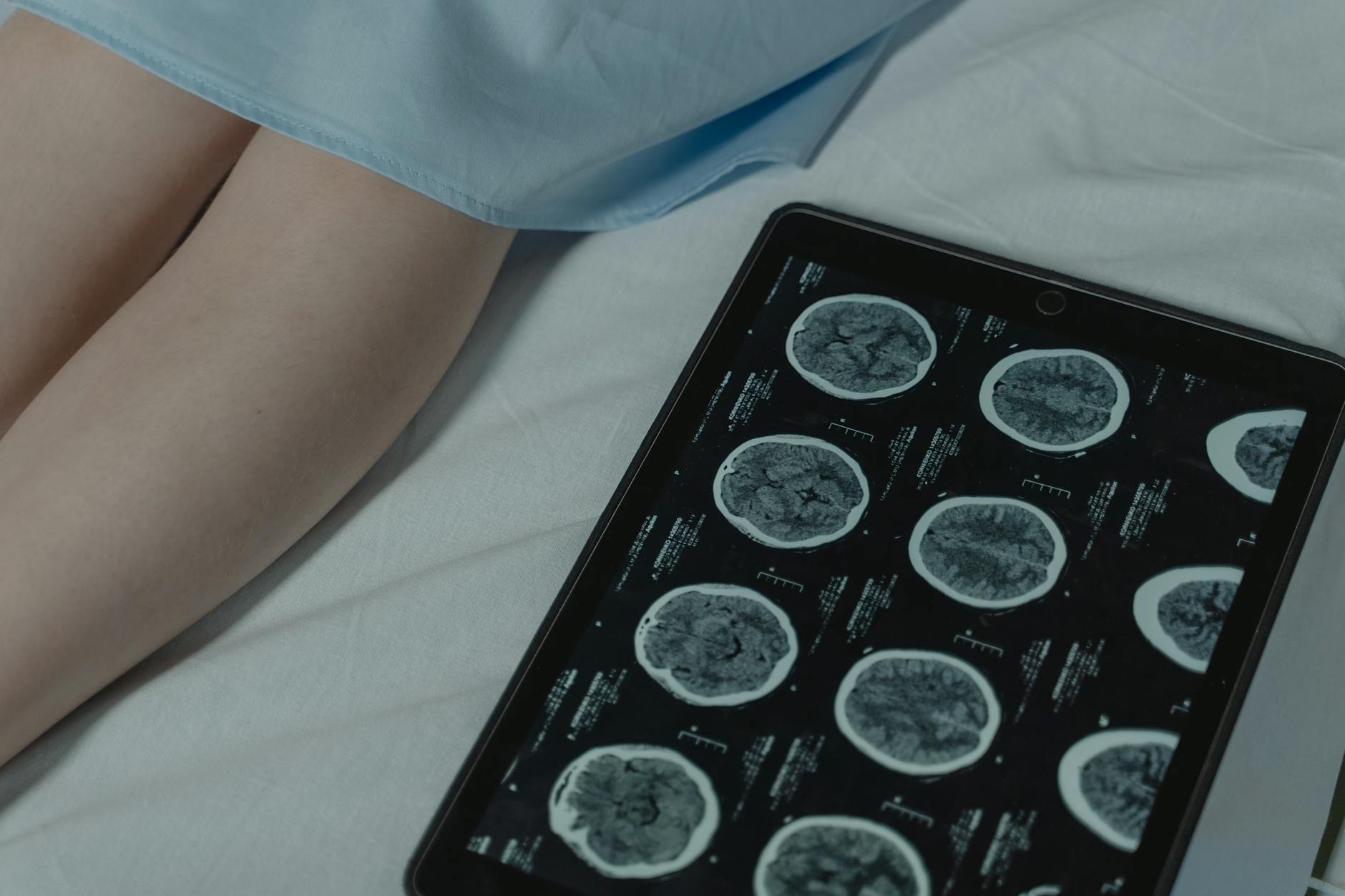

Disrupted sleep is both a symptom and an accelerator of dementia, creating one of the cruelest feedback loops in the disease. During deep sleep, the brain’s glymphatic system clears metabolic waste, including beta-amyloid protein. When sleep is fragmented — as it commonly is in Alzheimer’s — this clearance process is impaired, allowing amyloid to accumulate faster. Research from Washington University in St. Louis demonstrated that even a single night of disrupted slow-wave sleep increased amyloid levels in cerebrospinal fluid. Sleep apnea deserves special attention.

Obstructive sleep apnea is significantly more common in older adults and is both underdiagnosed and undertreated in people with dementia. Each apneic episode causes a brief drop in blood oxygen, and over years, these repeated episodes contribute to cerebrovascular damage. A 2020 meta-analysis in Sleep Medicine Reviews found that untreated sleep apnea was associated with a roughly two-fold increase in the rate of cognitive decline. CPAP treatment can help, but adherence is notoriously difficult even in cognitively intact adults, and it becomes far harder when the patient does not understand why a mask is being strapped to their face at night. Sedative sleep aids, while tempting for exhausted caregivers desperate for a quiet night, generally make the problem worse. Most sleep medications suppress the deep sleep stages that are most important for amyloid clearance. Non-pharmacological approaches — consistent bedtime routines, bright morning light exposure, limiting daytime napping, and treating pain that disrupts sleep — are more effective long-term, though they demand patience and consistency that may be difficult for overwhelmed caregivers to sustain.

How Repeated Hospitalizations and Delirium Cause Step-Down Declines

Hospital stays are among the most dangerous events for a person with dementia. The combination of an unfamiliar environment, disrupted routines, sleep deprivation, pain, anesthesia, and infection frequently triggers delirium — an acute state of confusion that is distinct from dementia but can permanently worsen it. Studies estimate that 40 to 50 percent of hospitalized older adults with dementia develop delirium, and a significant proportion never return to their pre-hospitalization cognitive baseline. Families often describe the phenomenon as a “step-down” — the person went in at one level and came out noticeably worse.

A practical example: an 80-year-old woman with mild Alzheimer’s falls and fractures her hip. The surgery goes well, but in the hospital she becomes severely confused, pulls out her IV, and does not recognize her family for three days. She eventually stabilizes but can no longer manage her own medications or cook a simple meal, tasks she handled before the fall. Her dementia has effectively jumped forward by a year or more. Strategies to reduce this risk include having a family member present around the clock, minimizing sedating medications during the stay, maintaining orientation cues like a visible clock and familiar photos, and pushing for the earliest safe discharge.

Emerging Research on Inflammation and Gut Health

The role of chronic systemic inflammation in dementia progression is one of the most active areas of current research. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 have been linked to faster cognitive decline in multiple longitudinal studies. Researchers are investigating whether anti-inflammatory interventions — ranging from diet modifications to repurposed medications — might slow progression, though no clinical trials have yet produced definitive results. The gut-brain axis is a newer frontier.

Early evidence suggests that the composition of gut bacteria may influence neuroinflammation and amyloid metabolism. A 2023 study in Science Translational Medicine found that specific gut bacterial profiles were associated with higher amyloid burden in cognitively impaired adults. This research is still preliminary, and no one should be taking specific probiotics based on these findings yet, but it points to a future where managing dementia progression might include attention to digestive health alongside cardiovascular and neurological care. The most honest summary of where this science stands is promising but unproven.

Conclusion

Dementia progression is not a single predetermined slide. It is shaped by a constellation of factors — cardiovascular health, medication choices, social engagement, sleep quality, nutrition, physical activity, depression, and the management of acute events like hospitalizations. While no combination of interventions can stop the underlying neurodegenerative process, addressing the modifiable accelerators can meaningfully extend the period of higher functioning and better quality of life.

The difference between aggressive management of these factors and neglecting them can amount to years of preserved independence. For families and caregivers, the most important step is a comprehensive assessment with a geriatrician or dementia specialist who looks beyond the diagnosis itself to evaluate all the contributors discussed here. Medication reviews, blood pressure management, depression screening, sleep assessment, and nutritional monitoring should be ongoing parts of dementia care, not one-time events. The goal is not to promise a cure but to fight for every good day that can be preserved.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can dementia suddenly get worse overnight?

A sudden worsening usually signals a treatable problem — a urinary tract infection, delirium, medication side effect, or depression — rather than a true leap in the underlying disease. Rapid changes should always prompt a medical evaluation because the cause is often reversible.

Does alcohol speed up dementia?

Heavy alcohol consumption is clearly associated with faster cognitive decline and is an independent risk factor for dementia. Even moderate drinking in someone already diagnosed may worsen symptoms by interacting with medications, disrupting sleep, and increasing fall risk. There is no evidence that any amount of alcohol slows dementia.

How much does physical exercise actually slow dementia progression?

Studies suggest moderate aerobic exercise can modestly slow functional decline, with the most consistent benefits seen in people with mild to moderate dementia. The effect is real but not dramatic — think months of preserved function rather than years. The exercise must be sustained and appropriate to the person’s physical ability.

Does keeping the brain active with puzzles slow progression?

Cognitive stimulation — including puzzles, conversation, music, and structured activities — shows modest benefits in maintaining function, particularly in mild stages. However, activities that cause frustration or highlight failures can increase agitation and worsen behavioral symptoms. The activity should match the person’s current ability, not their former capacity.

Are there foods that speed up or slow dementia progression?

No single food has been proven to alter dementia progression. However, dietary patterns matter. Diets high in processed foods, sugar, and saturated fat are associated with faster decline, while Mediterranean-style diets rich in vegetables, fish, nuts, and olive oil are associated with slower decline. Maintaining adequate caloric intake and hydration is often more immediately important than optimizing specific nutrients.

Does stress speed up dementia?

Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which damages the hippocampus — the brain region most affected in early Alzheimer’s. Caregiver stress can also indirectly accelerate decline by leading to inconsistent care routines, missed medications, and reduced social engagement for the person with dementia. Managing stress in both the patient and caregiver is a legitimate part of slowing progression.