When a brain MRI report comes back mentioning white matter disease, it can feel alarming — especially if you or a loved one weren’t expecting it. White matter disease refers to damage to the white matter of the brain, which shows up on MRI scans as bright spots, technically called white matter hyperintensities (WMH) or white matter lesions (WML). These bright areas are visible on specific MRI sequences called T2-weighted and FLAIR images, and they indicate areas where the brain’s communication fibers have been affected, usually by reduced blood flow over time. In most cases, this is a sign of small vessel disease — meaning the tiny blood vessels supplying the brain’s interior have been damaged, often silently, over years.

To put this in concrete terms: imagine a 68-year-old woman who goes in for an MRI after complaining of occasional forgetfulness and slower walking. The scan comes back showing “scattered periventricular and subcortical white matter hyperintensities.” Her neurologist explains this is white matter disease, likely linked to her long-standing high blood pressure. She has no idea how long it has been there. This scenario plays out in neurology offices every day — because white matter disease is extraordinarily common, frequently asymptomatic in its early stages, and often discovered incidentally. This article covers what the finding actually means, how common it is by age, what causes it, what symptoms it can produce, and what can realistically be done about it.

Table of Contents

- What Does White Matter Disease Mean on a Brain MRI — and What Are Those Bright Spots?

- How Common Is White Matter Disease, and When Is It Considered Normal Aging?

- What Causes White Matter Disease — Vascular Risk Factors and Beyond

- What Symptoms Does White Matter Disease Cause — and When Does It Stay Silent?

- The Risks White Matter Disease Carries — Stroke, Dementia, and Cognitive Decline

- Can White Matter Disease Be Treated or Reversed?

- What to Expect Going Forward — Monitoring and Long-Term Outlook

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Does White Matter Disease Mean on a Brain MRI — and What Are Those Bright Spots?

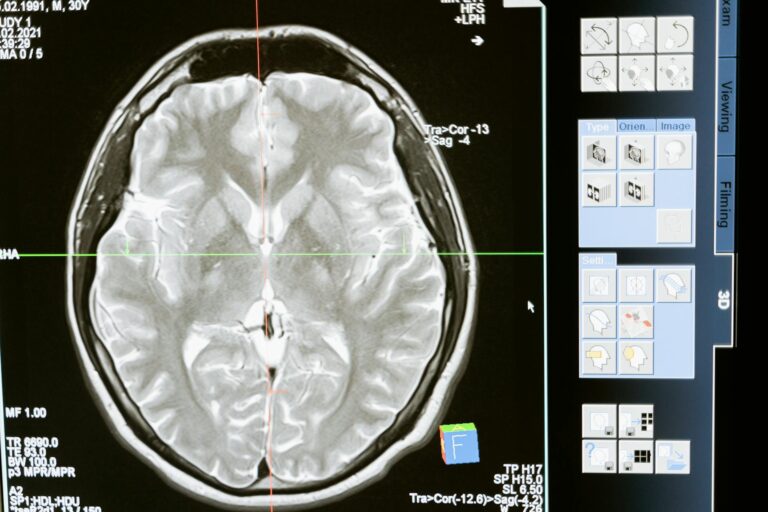

The brain is divided into gray matter and white matter. Gray matter contains the neuron cell bodies — the computing centers. White matter contains the axons, the long fibers that connect different brain regions and allow them to communicate. These fibers are coated in myelin, a fatty insulating sheath that gives white matter its pale color and allows signals to travel quickly. When the white matter is damaged, those communication pathways degrade, which can affect everything from memory to movement to mood. On an MRI, damaged white matter appears bright white on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences.

This happens because injured tissue holds more water than healthy tissue, and water shows up as bright on these particular imaging protocols. A radiologist reading the scan will typically describe these as “hyperintensities” — not because they are glowing or active, but simply because they are more intense (brighter) than surrounding normal white matter. The terms white matter disease, white matter lesions, and white matter hyperintensities are often used interchangeably in clinical reports, though white matter disease tends to be used when the pattern suggests a chronic, ongoing process rather than a single acute event. It is worth understanding what the MRI is and is not telling you. The scan identifies where damage has occurred and gives a sense of volume and distribution, but it does not directly explain why the damage happened. That requires clinical context — your age, medical history, blood pressure records, and symptoms. A single small lesion in a 75-year-old with hypertension means something very different from extensive confluent lesions in a 35-year-old with no vascular risk factors.

How Common Is White Matter Disease, and When Is It Considered Normal Aging?

White matter disease is one of the most common incidental findings on brain MRI in older adults — and its prevalence increases sharply with age. Roughly 10 to 20 percent of people around age 60 show some degree of white matter hyperintensities on MRI. By the time people pass 60, more than half will have detectable lesions. By age 90, the prevalence approaches 100 percent. In other words, nearly everyone who lives long enough will develop some white matter changes on imaging. This raises an important and often confusing question: if it is so common, does that mean it is normal? The honest answer is that mild white matter changes in an older adult with vascular risk factors are extremely common and do not by themselves constitute an emergency. Many people with these findings on MRI have no symptoms whatsoever.

However, common does not mean inconsequential. Even mild to moderate white matter disease is associated with measurable increases in the risk of stroke, cognitive decline, and dementia — the lesions are a marker that something has been wrong with the brain’s blood supply, and that process, if unchecked, tends to progress. The important caveat here is that distribution and severity matter enormously. Small, scattered lesions — especially in the subcortical regions — are far less concerning than confluent (merged, extensive) lesions near the brain’s ventricles, called periventricular lesions. The Fazekas scale is one tool radiologists and neurologists use to grade the burden of white matter disease from 0 to 3. A Fazekas score of 1 (mild, punctate lesions) in a 72-year-old with controlled blood pressure is a very different clinical picture from a Fazekas score of 3 (extensive, confluent lesions) in a 58-year-old. If a relatively young person — say, under 50 — has significant white matter lesions, that warrants a more urgent and thorough investigation for less common causes.

What Causes White Matter Disease — Vascular Risk Factors and Beyond

The most common underlying cause of white matter disease is chronically reduced blood flow to the nerve fibers of the brain’s interior. The brain’s white matter is particularly vulnerable because it sits at the end of long, small arterial branches with limited redundancy. When those small vessels become stiff, narrowed, or damaged — a process called small vessel disease or cerebral small vessel disease — the white matter they supply becomes chronically underperfused. Over time, this shows up as hyperintensities on MRI. High blood pressure is the single most important and modifiable risk factor. Poorly controlled hypertension damages the walls of small cerebral vessels over years, progressively compromising blood flow. Diabetes, high cholesterol, and smoking all contribute through overlapping mechanisms — endothelial dysfunction, accelerated atherosclerosis, and increased blood viscosity.

This is why white matter disease is so much more prevalent in people with multiple vascular risk factors, and why managing those factors is the primary treatment strategy. Not all white matter disease is vascular in origin, and this is an important distinction clinicians must make. Multiple sclerosis causes white matter lesions through a completely different mechanism — immune-mediated demyelination, where the body’s immune system attacks the myelin sheath directly. MS lesions tend to have a characteristic distribution: they often appear in the periventricular region perpendicular to the ventricles (called Dawson’s fingers on MRI), in the corpus callosum, near the optic nerves, and in the brainstem and spinal cord. Migraines, particularly with aura, are also associated with small white matter lesions, most often in the deep white matter. Rare genetic conditions called leukodystrophies cause extensive white matter damage from birth or early childhood. Micro-hemorrhages and gliosis (scarring) can also produce similar-appearing changes. Distinguishing between these causes requires combining the MRI pattern with the patient’s age, symptoms, and clinical history.

What Symptoms Does White Matter Disease Cause — and When Does It Stay Silent?

One of the most disorienting aspects of white matter disease for patients and families is that it can be completely silent. Many people find out they have it on an MRI done for an entirely unrelated reason — a headache workup, a pre-operative evaluation, or a scan ordered after a minor injury. In these cases, the lesions may have been accumulating for years without producing any noticeable symptoms. This is more likely when the lesion burden is mild to moderate and when the affected areas do not involve critical circuits. When white matter disease does cause symptoms, they tend to involve the domains you would expect from disrupted brain connectivity rather than focal brain region damage. The classic presentation includes slowed thinking and processing speed, difficulty with executive function (planning, sequencing, multitasking), and memory problems — though the memory issues in white matter disease tend to differ from those in Alzheimer’s disease. People with Alzheimer’s typically have difficulty encoding new memories, while those with white matter disease often have trouble retrieving information quickly — a slowed, disconnected quality to their thinking.

Walking difficulties are also common: a shortened stride, unsteadiness, and falls. A telling clinical sign is difficulty doing two things simultaneously — what neurologists call a dual-task deficit. A person who walks normally when focused but slows dramatically when asked to carry on a conversation at the same time is showing a hallmark pattern of white matter dysfunction. Other symptoms that can develop include mood changes, particularly depression, urinary incontinence as white matter tracts controlling bladder function are affected, and in more advanced cases, a full syndrome of vascular cognitive impairment or vascular dementia. The severity and nature of symptoms depend heavily on where in the brain the lesions are concentrated and how much total volume is affected. Lesions in the frontal lobe connections tend to produce executive dysfunction; lesions in posterior regions may affect processing speed and visual integration. This is why two people with the same Fazekas score can have very different clinical presentations.

The Risks White Matter Disease Carries — Stroke, Dementia, and Cognitive Decline

White matter disease is not simply a passive marker of aging. It carries real and measurable clinical risks, even in people who feel fine at the time of diagnosis. Research has consistently shown that the presence of white matter hyperintensities significantly increases the risk of future stroke — independently of other known vascular risk factors. In other words, even after accounting for high blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking, people with white matter disease have a higher likelihood of suffering a stroke than those without it. The white matter lesions themselves reflect a vulnerable cerebrovascular state. The risk of cognitive decline and dementia is also substantially elevated. White matter disease is associated with impairments in executive function and processing speed even in people who do not meet criteria for dementia at the time of diagnosis.

Over time, individuals with greater lesion burden are more likely to develop vascular dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, or mixed dementia (a combination of both). This is clinically important because it means white matter disease is not just an imaging curiosity — it is a risk stratifier that should inform how aggressively vascular risk factors are managed. Cardiovascular death risk is also increased in people with significant white matter disease, reflecting the shared vascular biology underlying both brain and heart disease. A critical warning: the relationship between white matter disease and dementia risk is not linear or simple. Having white matter hyperintensities does not mean someone will develop dementia — many people live with mild to moderate lesion burden for decades without significant cognitive decline, particularly if their vascular risk factors are well controlled. However, the combination of white matter disease with early cognitive symptoms, or with other imaging findings like hippocampal atrophy, substantially raises concern. Clinicians should not reassure patients too broadly just because the lesions appear mild — longitudinal follow-up and aggressive risk factor modification remain important.

Can White Matter Disease Be Treated or Reversed?

There is no treatment that directly reverses or removes white matter lesions once they have formed. This is one of the harder truths of the condition. However, slowing progression is achievable and important. The management strategy centers entirely on addressing the underlying causes — the vascular risk factors that have been damaging small blood vessels. Controlling blood pressure is the most impactful intervention, and studies have shown that aggressive blood pressure management can slow the accumulation of new white matter lesions over time.

The same applies to managing blood sugar in diabetes, reducing LDL cholesterol, and stopping smoking. This means the conversation after a white matter disease diagnosis should be less about the lesions themselves and more about what is driving them. A person who discovers white matter disease and uses it as motivation to finally address their hypertension and sedentary lifestyle is doing the single most meaningful thing available to them. Lifestyle factors — regular aerobic exercise, heart-healthy diet, sleep quality — all support cerebrovascular health broadly. In cases where a non-vascular cause like MS is identified, disease-specific treatments targeting the underlying mechanism become the priority.

What to Expect Going Forward — Monitoring and Long-Term Outlook

For most people diagnosed with white matter disease, the practical next step is a conversation with a neurologist or primary care physician about vascular risk factor optimization, followed by a plan for monitoring. Repeat MRI scans — typically every one to three years depending on lesion burden and clinical trajectory — can track whether lesions are stable or progressing. Stable lesions in the context of well-controlled risk factors are reassuring.

Progressive lesions despite good risk factor control may prompt investigation for less common causes or referral to a cognitive neurologist. The long-term outlook depends enormously on the severity of the disease at diagnosis and on how aggressively contributing factors are managed afterward. Mild white matter disease in an otherwise healthy person with newly diagnosed and now-controlled hypertension carries a very different prognosis than extensive lesions in someone with longstanding uncontrolled diabetes and a history of small strokes. The field of cerebrovascular research is actively exploring whether certain medications and interventions beyond standard risk factor control might offer additional protection — but for now, the fundamentals remain the most powerful tools available.

Conclusion

White matter disease on a brain MRI is a common finding that reflects cumulative damage to the brain’s communication fibers, most often caused by small vessel disease driven by vascular risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, and smoking. It appears as bright spots on T2-weighted and FLAIR MRI sequences and becomes increasingly prevalent with age, present in over half of people over 60 and approaching universal prevalence by age 90. It can be entirely asymptomatic or can cause a recognizable pattern of slowed cognition, walking difficulties, and mood changes, and it carries meaningful risks of future stroke, cognitive decline, and dementia.

The most important takeaway is that the diagnosis is not a verdict but a signal. There is no treatment to undo existing lesions, but there is strong evidence that controlling blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol, and other vascular risk factors can slow progression and reduce downstream risks. Anyone who receives this finding on an MRI should discuss it directly with their physician — not to panic, but to understand what risk factors may be driving it and what proactive steps can meaningfully change the trajectory.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is white matter disease the same as dementia?

No. White matter disease is an MRI finding that increases the risk of cognitive decline and dementia, but it is not the same as dementia. Many people with white matter lesions maintain normal cognitive function. Dementia requires a clinical diagnosis based on functional impairment in daily life, not imaging alone.

Should I be worried if my MRI report mentions white matter hyperintensities?

Not necessarily alarmed, but it warrants a conversation with your doctor. The significance depends heavily on your age, the extent of the lesions, and your underlying medical history. Mild scattered lesions in a person over 65 with controlled blood pressure are common and may require only monitoring. Extensive lesions or lesions in a younger person deserve more urgent evaluation.

Can white matter disease get better on its own?

Existing white matter lesions do not reverse or disappear. However, controlling vascular risk factors — especially blood pressure — can slow or halt the accumulation of new lesions. The goal of treatment is stabilization and risk reduction, not reversal.

What is the difference between white matter disease and a stroke?

A stroke is an acute event caused by sudden loss of blood flow (ischemic) or bleeding (hemorrhagic) in the brain. White matter disease develops slowly over time due to chronically reduced blood flow to small vessels. They share similar risk factors and white matter disease increases stroke risk, but they are distinct conditions. White matter lesions can sometimes represent the cumulative residue of many tiny, silent strokes (lacunar infarcts).

Does white matter disease run in families?

There is a genetic component to white matter disease. Certain inherited conditions — like CADASIL, a genetic small vessel disease — cause extensive white matter lesions and are directly inherited. More commonly, genetic factors that increase susceptibility to hypertension, diabetes, and other vascular risk factors indirectly raise the likelihood of developing white matter disease. If you have a strong family history of stroke or early dementia, mention it to your neurologist.

Does white matter disease always progress?

Not inevitably. Progression is more likely when underlying risk factors remain uncontrolled. Studies have shown that people who achieve good blood pressure control, exercise regularly, and avoid smoking tend to have slower rates of white matter lesion accumulation. Regular follow-up imaging helps track whether lesions are stable or growing.