End-stage vascular dementia looks like a person who has become almost entirely dependent on others for every aspect of daily life. They are typically bed-bound or confined to a wheelchair, unable to speak more than a few words if at all, no longer recognizing family members, and experiencing repeated infections that grow harder to treat with each occurrence. The body, weakened by years of vascular damage to the brain, begins shutting down in ways that are painful to witness but important to understand — because knowing what to expect helps families make better decisions about comfort care, dignity, and when to shift the focus from treatment to peace. Vascular dementia accounts for roughly 15 to 20 percent of all dementia cases, making it the second most common form after Alzheimer’s disease. But it behaves differently.

Where Alzheimer’s typically follows a slow, steady decline, vascular dementia often moves in sudden, stepwise drops — periods where the person seems stable, followed by sharp worsening that usually corresponds to a new stroke or vascular event. This pattern can make the end stage feel like it arrives without warning, even when the disease has been progressing for years. Average survival after a vascular dementia diagnosis is three to five years, though in the very late stage with severe cognitive decline, life expectancy narrows to roughly one to two years. This article covers what the final stage actually looks like in concrete terms — the physical changes, the cognitive losses, the signs that death may be approaching, and what families and caregivers can realistically do during this period. None of it is easy reading. But families who understand what is happening are better equipped to advocate for their loved one’s comfort and to process their own grief.

Table of Contents

- What Does End-Stage Vascular Dementia Actually Look Like Day to Day?

- Physical Changes and Complications in the Final Stage

- Cognitive Loss and Communication Breakdown

- Recognizing When Death May Be Approaching

- Why Vascular Dementia Carries a Worse Prognosis

- The Emotional Weight on Caregivers and Family

- Planning Ahead and the Role of Palliative Care

- Conclusion

What Does End-Stage Vascular Dementia Actually Look Like Day to Day?

The daily reality of end-stage vascular dementia is round-the-clock care for a person who can no longer do anything independently. Full-time, 24-hour supervision is required — patients are completely dependent for all activities of daily living, including eating, bathing, toileting, and repositioning in bed. Most have lost the ability to walk without assistance, and many are fully bed-bound, which increases their risk of pressure sores and skin breakdown. Incontinence is complete, with total loss of both bowel and bladder control. A person who was once active and independent may now spend most of the day sleeping, eyes closed, unresponsive to voices they once loved. Compare this to the middle stages, where someone might still manage a short, supported walk down the hallway or respond to a familiar song. In end-stage vascular dementia, those moments become rare or disappear entirely.

The person may no longer track movement with their eyes. They may not react when a grandchild enters the room. Their facial expressions often flatten. Caregivers sometimes describe it as the person being “present but unreachable” — their body is there, but the connection that made them who they were has been severely damaged by repeated vascular events in the brain. What makes this stage particularly difficult for families is that it can look different from what they expected. Many people picture dementia’s end stage as a gradual fading, like a candle burning down. With vascular dementia, the person may have seemed relatively stable last month, then suffered a small stroke that suddenly took away their ability to swallow or speak. That stepwise progression means the end stage can arrive abruptly, leaving families scrambling to understand a new baseline that is dramatically worse than what they were managing just weeks earlier.

Physical Changes and Complications in the Final Stage

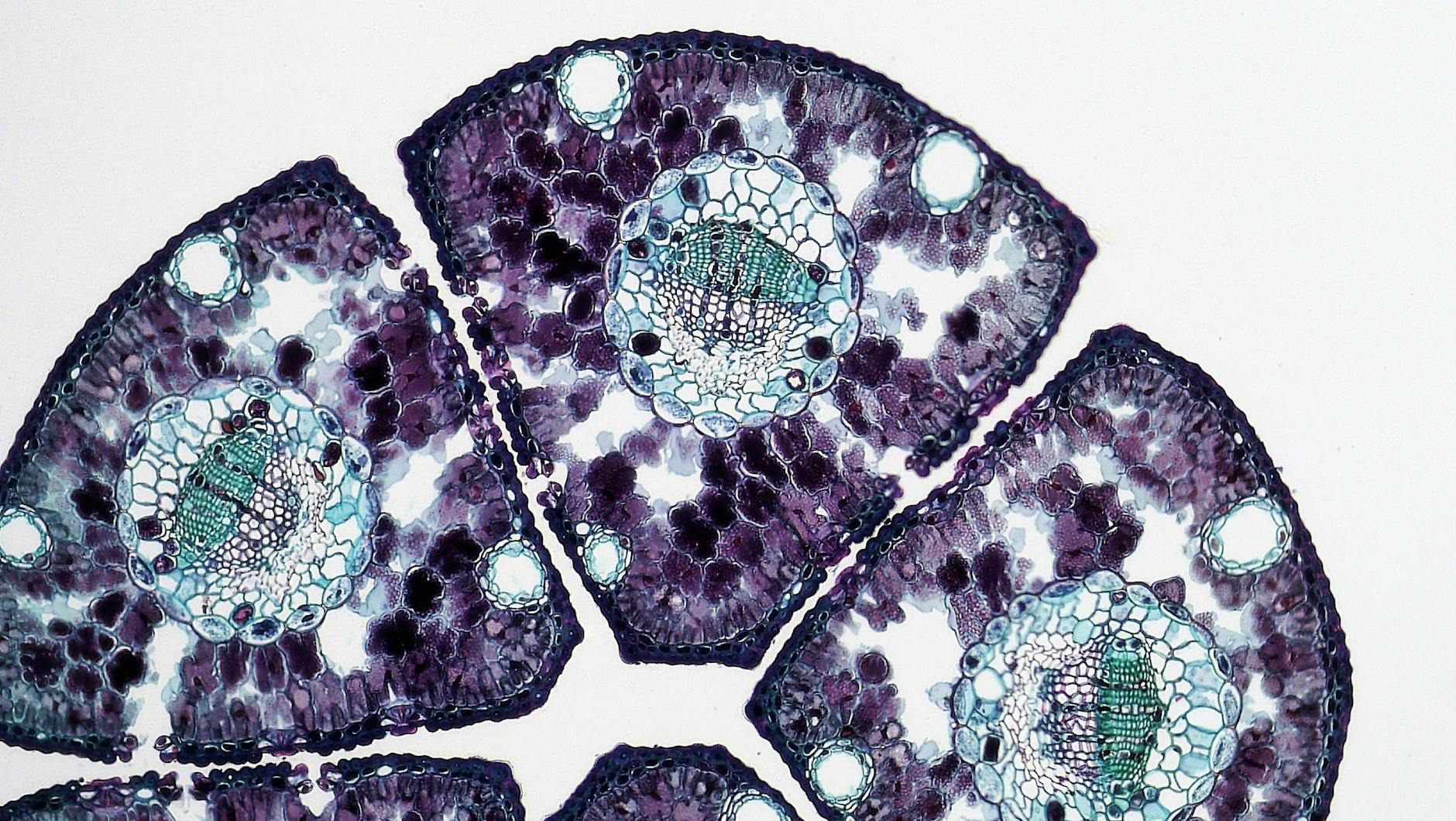

The physical decline in end-stage vascular dementia is driven by the brain’s increasing inability to manage basic bodily functions. One of the most significant complications is dysphagia — difficulty swallowing — which develops as the brain loses control over the muscles involved in eating and drinking. This is not a minor inconvenience. Dysphagia dramatically increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia, where food or liquid enters the lungs instead of the stomach, causing infection. Aspiration pneumonia is one of the leading causes of death in end-stage dementia, and it can develop rapidly. Significant weight loss is common even when caregivers are making every effort to provide adequate nutrition. The body’s metabolism changes. The person may refuse food, turn their head away, or simply lack the coordination to chew and swallow safely. Frailty sets in, and with it a weakened immune system.

Infections become frequent — urinary tract infections, chest infections, pneumonia. Each infection takes a greater toll, and the person recovers a little less each time. For families, watching this cycle of infection, partial recovery, and then another infection is exhausting and heartbreaking. However, it is important to understand that not every person with end-stage vascular dementia experiences every complication on the same timeline. Some individuals maintain the ability to swallow soft foods for longer than expected. Others may lose mobility early but retain some facial responsiveness. The general trajectory is toward total dependence, but the specific path varies. This matters because families sometimes compare their loved one’s experience to descriptions they have read online and feel either alarmed that things are progressing faster than expected or confused that certain symptoms have not appeared. Each brain has been damaged in a unique pattern by the vascular events, and that pattern shapes which abilities are lost first.

Cognitive Loss and Communication Breakdown

By the end stage, the cognitive damage from vascular dementia is profound. Severe memory loss means the person typically no longer recognizes family members or caregivers. A daughter who visits every day may be treated as a stranger, or the person may show no visible reaction to her presence at all. Many individuals become completely non-verbal, limited to occasional sounds, a few repeated words, or silence. The ability to process or respond to the environment drops to very low or nonexistent levels. This is one of the areas where vascular dementia can differ from late-stage Alzheimer’s in subtle ways. Because vascular dementia is caused by damage to specific blood vessels in the brain, the pattern of cognitive loss depends on where the strokes or vascular events occurred.

Some people lose language early but retain emotional responses to music or touch for longer. Others may lose spatial awareness and physical coordination before language goes. A man with extensive damage to the left hemisphere might stop speaking months before he stops responding to his wife holding his hand. In contrast, Alzheimer’s disease tends to erode memory and cognition in a more uniform, predictable sequence. For caregivers, the loss of communication is often the most isolating part of end-stage dementia. When a person cannot tell you they are in pain, uncomfortable, or afraid, you have to read subtle cues — a furrowed brow, a change in breathing, tension in the hands. Trained hospice and palliative care staff are experienced in interpreting these non-verbal signals, and their involvement becomes particularly valuable at this stage. Families should not feel they need to decode everything alone.

Recognizing When Death May Be Approaching

Knowing the signs that death is near allows families to prepare emotionally and to make decisions about where and how their loved one spends their final days. Several physical changes tend to cluster in the last weeks and days of life. The person may begin sleeping most of the time and become difficult to rouse. Food and fluid intake drops to minimal or nothing, even when offered gently. Infections recur and no longer respond well to antibiotics or other treatments. Breathing patterns often change — families may notice Cheyne-Stokes respiration, a cycle of deep breaths followed by pauses and then shallow breathing before the cycle repeats. Skin color can change, with mottling appearing especially in the hands and feet, giving the skin a blotchy, purplish appearance as circulation slows.

There may also be periods of restlessness and agitation alternating with complete unresponsiveness. These fluctuations can be confusing and distressing for family members who are unsure whether their loved one is in pain or simply in the process of dying. The tradeoff families face at this point is between interventions and comfort. A recurring pneumonia can be treated with another round of antibiotics — but should it be? The infection will likely return. A feeding tube can deliver nutrition — but will it improve quality of life or prolong suffering? These are deeply personal decisions, and there is no universal right answer. What matters is that families discuss these choices with the care team in advance, ideally when the person first enters end-stage dementia, rather than in the crisis of the moment. Hospice referrals, when made early enough, give families more support and more time to think clearly about what their loved one would have wanted.

Why Vascular Dementia Carries a Worse Prognosis

Vascular dementia has a poorer prognosis than Alzheimer’s disease, and the reason is straightforward: the same cardiovascular problems that caused the dementia in the first place continue to threaten the person’s life. The leading causes of death in end-stage vascular dementia are stroke, heart disease, and infection. A person with vascular dementia is living with damaged blood vessels, often alongside conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or atrial fibrillation. Any of these can trigger a fatal event at any time, independent of how the dementia itself is progressing. This is an important distinction that families sometimes miss.

With Alzheimer’s, the typical cause of death is a complication of the dementia itself — most often pneumonia or another infection in a body weakened by advanced disease. With vascular dementia, a person who might have had months of life left from the dementia perspective can die suddenly from a major stroke or heart attack. It means that life expectancy estimates are less reliable, and families should be prepared for the possibility of sudden death even when the person’s dementia symptoms seem stable. The CDC reports that dementia is now a leading cause of death among Americans aged 65 and older, with mortality rates climbing in recent years. For families dealing with vascular dementia specifically, this statistical reality underscores the importance of having end-of-life conversations early — not because hope is lost, but because the unpredictable nature of vascular events means there may not be a clear window of gradual decline that signals “now is the time to talk.”.

The Emotional Weight on Caregivers and Family

Caring for someone in end-stage vascular dementia is among the most physically and emotionally demanding experiences a person can face. The round-the-clock nature of care — turning the person every two hours to prevent bedsores, managing incontinence, monitoring for signs of pain or infection — takes a toll that no amount of love fully cushions. Many family caregivers report feeling that they are grieving someone who is still alive, a phenomenon sometimes called anticipatory grief or ambiguous loss.

A wife who has been caring for her husband through years of stepwise decline may find the end stage particularly cruel, because each sudden drop took away something specific — first his ability to manage finances, then his ability to dress himself, then his recognition of her face. Unlike a gradual fade, each loss was abrupt and stark. Support from hospice teams, respite care, and dementia caregiver support groups is not optional at this stage — it is essential for the caregiver’s own health and wellbeing.

Planning Ahead and the Role of Palliative Care

The single most useful thing families can do when a loved one enters the late stages of vascular dementia is to engage palliative care or hospice services early. These teams specialize in managing pain, discomfort, and distressing symptoms without aggressive interventions that are unlikely to improve outcomes. They also provide emotional and logistical support to family members — helping with advance directives, explaining what to expect, and being available during crises.

Looking ahead, there is growing recognition in the medical community that vascular dementia needs its own care frameworks rather than being lumped in with Alzheimer’s disease. The stepwise progression, the cardiovascular comorbidities, and the different patterns of cognitive loss all argue for a more tailored approach to end-of-life care. Families navigating this path today can advocate for that specificity by asking their medical team pointed questions: not just “what stage is the dementia?” but “what vascular risks remain, what complications should we prepare for, and what does comfort-focused care look like for this particular person?”.

Conclusion

End-stage vascular dementia is marked by complete dependence, loss of communication, bed-bound immobility, swallowing difficulties, recurrent infections, and a body that is slowly losing its ability to sustain basic functions. The stepwise nature of vascular dementia means these losses often arrive suddenly rather than gradually, and the ongoing cardiovascular risks mean that stroke or heart disease can end life at any point.

Average survival in the severe stage is one to two years, but individual variation is significant. For families, the most important steps are engaging hospice or palliative care early, having honest conversations about goals of care before a crisis forces the decision, and accepting support from professionals who understand what this stage demands. No one should navigate end-stage vascular dementia alone — not the person living with it, and not the people who love them.