Mixed dementia progresses through seven recognized stages, ranging from no visible impairment to complete dependence on round-the-clock care. These stages follow the Global Deterioration Scale, the same framework clinicians use for Alzheimer’s disease, but with an important distinction: because mixed dementia involves brain changes from two or more dementia types simultaneously, symptoms at each stage can be more noticeable and appear to progress more rapidly than they would with a single type of dementia alone. The most common combination is Alzheimer’s disease occurring alongside vascular dementia, though Lewy body dementia frequently co-occurs as well. Consider a 78-year-old woman whose family assumes her increasing forgetfulness is simply Alzheimer’s.

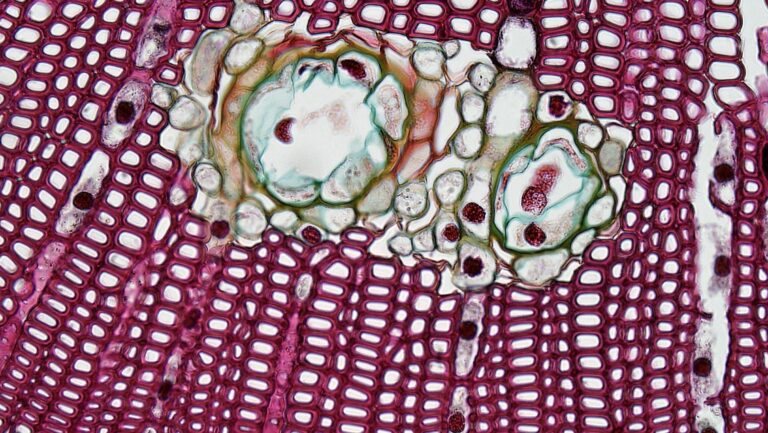

At autopsy, her brain reveals not only the amyloid plaques and tau tangles of Alzheimer’s but also significant small-vessel vascular disease that had gone undetected during her lifetime. Her case is far from unusual. A National Institute on Aging autopsy study found that 54 percent of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s actually had coexisting pathology, with vascular disease being the most common hidden contributor and Lewy bodies the second most common. This article walks through each of the seven stages of mixed dementia in detail, explains how the condition differs from single-type dementia in its progression and life expectancy, outlines the major risk factors, and addresses the current state of treatment options.

Table of Contents

- What Exactly Are the Seven Stages of Mixed Dementia and How Are They Defined?

- Why Mixed Dementia Progresses Differently Than a Single Diagnosis

- How Common Is Mixed Dementia and Why Is It So Often Missed?

- Managing Daily Life Through the Middle Stages of Mixed Dementia

- Risk Factors and the Limits of Prevention

- What Treatment Options Exist for Mixed Dementia Today

- Where Research Is Heading and What It Means for Families

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Exactly Are the Seven Stages of Mixed Dementia and How Are They Defined?

The seven stages of mixed dementia are mapped using the Global Deterioration Scale, originally developed by Dr. Barry Reisberg to chart the progression of cognitive decline. In Stage 1, there is no impairment whatsoever. A person functions normally, and no one around them would suspect anything is wrong, even though pathological brain changes may already be underway at the cellular level. Stage 2 brings very mild decline — the kind of memory lapses that most people, including doctors, would attribute to normal aging. Forgetting where you left your reading glasses or blanking on an acquaintance’s name falls into this category. By Stage 3, the changes become noticeable to family members and close colleagues.

A person in this stage may struggle to find the right word during conversation, lose track of recent events, or have trouble organizing a weekend trip they would have planned effortlessly a few years ago. Stage 4 marks a turning point: moderate decline that interferes with practical daily tasks like managing bills, following a recipe, or making plans for the week. This is frequently the stage at which a formal diagnosis occurs, because the difficulties are now too consistent to dismiss. Stages 5 through 7 represent the progressively severe end of the spectrum. At Stage 5, a person needs help choosing appropriate clothing and may become confused about the date or where they are. Stage 6 brings significant personality changes, difficulty recognizing family members, and possible incontinence, with substantial help required for nearly all daily activities. Stage 7, the final stage, involves the loss of the ability to communicate, walk, or perform any basic tasks independently. Full-time care is no longer optional — it is essential for survival.

Why Mixed Dementia Progresses Differently Than a Single Diagnosis

One of the most important things families need to understand about mixed dementia is that it does not simply follow the trajectory of whichever dementia type is dominant. When two types of brain pathology are operating at once — say, the slow plaque buildup of Alzheimer’s combined with the sudden, step-like damage caused by vascular events — the overall decline can feel unpredictable. A person might plateau for weeks and then drop sharply after a small stroke, or they might experience a steady cognitive slide punctuated by visual hallucinations that suggest a lewy body component. According to Dementia UK, having two types of dementia means symptoms can appear to progress more rapidly than they would with a single type. A 2018 Norwegian study put hard numbers to this observation, finding that mixed dementia takes approximately ten years off a person’s life expectancy.

Median survival figures offer further context: Alzheimer’s alone averages roughly six years from diagnosis, vascular dementia about four years, and Lewy body dementia also about four years. When these pathologies overlap, mortality risk increases beyond what either condition would cause on its own. However, progression speed is not uniform across all cases of mixed dementia. If the vascular component is driven by manageable factors like high blood pressure or diabetes, aggressively treating those conditions may slow the vascular damage even though the Alzheimer’s pathology continues. Conversely, if a person has both Alzheimer’s and Lewy body disease, the medication picture becomes more complicated because some drugs that help one condition can worsen symptoms of the other. Families should not assume that a mixed diagnosis automatically means the fastest possible decline — the specific combination matters enormously.

How Common Is Mixed Dementia and Why Is It So Often Missed?

The short answer is that mixed dementia is far more common than most people realize, and it is almost always underdiagnosed during a person’s lifetime. A striking autopsy study of 447 older adults who had been clinically diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease found that only 3 percent had Alzheimer’s changes alone. Fifteen percent turned out to have an entirely different cause of dementia, and a full 82 percent had Alzheimer’s plus at least one other dementia type. These are not fringe findings. Community-based autopsy cohorts consistently show that Alzheimer’s pathology appears in 19 to 67 percent of cases, Lewy body pathology in 6 to 39 percent, and vascular pathologies in 28 to 70 percent. The reason mixed dementia slips past clinicians is partly structural.

A standard diagnostic workup involves cognitive testing, brain imaging, and sometimes blood work, but these tools are better at confirming one major diagnosis than detecting layered pathologies. Vascular changes may show up on an MRI, but mild Lewy body involvement might not. Alzheimer’s biomarkers can dominate the clinical picture, causing doctors to stop looking once they find a plausible explanation. One-third of adults over age 85 have at least one type of dementia, and the older a person gets, the higher the probability that multiple pathologies are at work. For families, the practical takeaway is that if a loved one’s symptoms don’t quite fit the expected pattern — say they have Alzheimer’s but also experience Parkinsonian tremors or sudden stepwise declines rather than gradual worsening — it is worth raising the possibility of mixed dementia with their physician. A diagnosis that captures the full picture can lead to better-targeted care.

Managing Daily Life Through the Middle Stages of Mixed Dementia

Stages 4 and 5 are where the gap between a person’s remaining abilities and their care needs widens most rapidly, and they represent the period when practical planning matters more than almost anything else. At Stage 4, a person with mixed dementia may still recognize everyone in their family and hold a reasonable conversation, but they can no longer reliably manage finances, prepare meals safely, or keep medical appointments without reminders. At Stage 5, even choosing weather-appropriate clothing or bathing regularly becomes difficult without hands-on help. The tradeoff families face during these stages is between preserving independence and ensuring safety. Allowing a person to continue cooking, for example, maintains their sense of identity and routine, but a missed burner or a forgotten pot creates genuine danger.

Many caregivers find that supervised participation — chopping vegetables while someone else manages the stove, or sorting laundry while someone else handles the washer — offers a middle path. The comparison to single-type dementia matters here, too. A person with Alzheimer’s alone might lose cooking skills gradually and predictably, while someone with an added vascular component might manage fine on Monday and be dangerously confused on Wednesday after a small vascular event. Caregivers of people with mixed dementia often report that the inconsistency is harder to manage than the decline itself. Planning ahead for Stage 6 and beyond should begin during these middle stages, while the person with dementia can still participate in decisions about their future care. Legal documents, advance directives, and conversations about care preferences are far easier to address at Stage 4 than at Stage 6, when the person may no longer recognize family members or understand the implications of these choices.

Risk Factors and the Limits of Prevention

Mixed dementia is most common in people over age 65 and especially prevalent in those older than 75. The risk factors track closely with those for each individual dementia type: cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, and advancing age all contribute. Because vascular dementia is one of the most frequent co-occurring pathologies, anything that damages blood vessels — poorly controlled cholesterol, sedentary lifestyle, chronic hypertension — increases the odds of developing a mixed picture. The limitation that families need to hear honestly is that no amount of cardiovascular risk management guarantees protection against the Alzheimer’s or Lewy body components of mixed dementia. A person can exercise daily, maintain perfect blood pressure, and never smoke, and still develop Alzheimer’s pathology driven by genetics and mechanisms researchers do not yet fully understand.

What vascular risk reduction can do is remove one layer of damage from the equation. If the brain is already contending with amyloid plaques, keeping its blood supply healthy gives it a better chance of compensating for longer. There is also a warning worth stating plainly: the “brain health” industry is full of supplements, games, and programs marketed as dementia prevention. While cognitive engagement and physical exercise show genuine associations with delayed symptom onset in research, no commercial product has been proven to prevent mixed dementia. Families should be skeptical of any product claiming otherwise and focus their energy on established medical interventions and care planning.

What Treatment Options Exist for Mixed Dementia Today

There is no cure for mixed dementia, and no treatment that reverses the brain changes once they have occurred. Current medications focus on managing symptoms, primarily through drugs originally developed for Alzheimer’s disease. Cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine may help slow cognitive decline and provide modest, temporary improvements in memory and attention.

Memantine, which works on a different neurotransmitter system, is sometimes prescribed for moderate to severe cases. For the vascular component, treatment centers on controlling the underlying cardiovascular conditions: blood pressure medications, statins, diabetes management, and anticoagulants if blood clots are a concern. A person with a Lewy body component may benefit from certain Parkinson’s medications for motor symptoms, but these must be prescribed carefully because some antipsychotic drugs commonly used for behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s can cause severe, potentially fatal reactions in people with Lewy body disease. This is one of the strongest arguments for pursuing an accurate mixed dementia diagnosis — the wrong medication can do real harm.

Where Research Is Heading and What It Means for Families

The 2025 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report from the Alzheimer’s Association emphasizes that prevention and treatment efforts must become multifaceted to match the complex, multi-morbid nature of brain pathologies in older adults. This is a meaningful shift in thinking. For decades, dementia research focused overwhelmingly on single-target therapies — clear the amyloid, stop the tau, fix the one broken pathway.

The growing recognition that most older adults with dementia have mixed pathology is pushing researchers toward combination approaches and broader diagnostic tools, including blood-based biomarkers that could one day detect multiple dementia types from a single draw. For families navigating a mixed dementia diagnosis today, the most useful forward-looking insight is that the field is moving toward earlier and more accurate detection. As diagnostic technology improves, clinicians will be better positioned to identify mixed pathology while a person is still alive, rather than relying on autopsy findings that come too late to guide treatment. In the meantime, the best strategy remains a combination of aggressive cardiovascular risk management, honest care planning, and working with a medical team that takes the complexity of mixed dementia seriously.

Conclusion

Mixed dementia moves through seven stages from invisible brain changes to total dependence, and its course is shaped by whichever combination of pathologies is present. The research makes one thing clear: mixed dementia is not rare. It is likely the norm rather than the exception in older adults, with autopsy studies consistently showing that the vast majority of people diagnosed with a single dementia type actually had multiple pathologies at work.

Understanding this changes how families should think about diagnosis, treatment, and care planning. The most actionable steps for families are to push for thorough diagnostic evaluations that consider multiple dementia types, to manage cardiovascular risk factors aggressively, to plan legal and care arrangements during the middle stages while meaningful participation is still possible, and to work with physicians who understand the medication risks unique to mixed presentations. Mixed dementia is a harder road than a single diagnosis, but informed caregiving and realistic expectations make a genuine difference in quality of life for both the person with dementia and those who care for them.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can mixed dementia be diagnosed without an autopsy?

It can be suspected and sometimes identified through a combination of cognitive testing, brain imaging, and clinical observation, but definitive confirmation of which pathologies are present has traditionally required autopsy. Advances in biomarker research are beginning to improve living diagnosis, though the technology is not yet widely available.

Is mixed dementia hereditary?

No single gene causes mixed dementia. However, genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease (such as the APOE-e4 allele) and cardiovascular conditions that contribute to vascular dementia can run in families. Having a parent with dementia increases your statistical risk, but it does not make a diagnosis inevitable.

How fast does mixed dementia progress compared to Alzheimer’s alone?

Mixed dementia generally progresses more rapidly than a single dementia type. A 2018 Norwegian study found that mixed dementia reduces life expectancy by approximately ten years. The median survival for Alzheimer’s alone is about six years, while vascular and Lewy body dementia average about four years each, and overlapping pathologies increase mortality risk further.

What is the most common type of mixed dementia?

The most common combination is Alzheimer’s disease occurring alongside vascular dementia. This pairing was identified as the most frequent in multiple autopsy studies, including a major National Institute on Aging study that found vascular disease to be the most common coexisting abnormality in people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Are there medications specifically approved for mixed dementia?

No medications are specifically approved for mixed dementia. Doctors typically prescribe Alzheimer’s medications such as cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine to address cognitive symptoms, along with cardiovascular treatments for the vascular component. Medication choices must be made carefully, especially if Lewy body pathology is involved, because some drugs can worsen symptoms or cause dangerous reactions.