The signs that dementia is getting worse typically show up as noticeable declines across several areas of daily life: increasing memory gaps that go beyond forgetting names to forgetting entire conversations or recent events, growing difficulty with tasks that were once routine like cooking a familiar recipe or managing medications, personality shifts that seem out of character, and a mounting need for help with basic activities such as dressing or bathing. These changes don’t usually arrive all at once. They tend to creep in over weeks or months, and family members often recognize the pattern only in hindsight, realizing that the person who confidently drove to the grocery store six months ago now gets lost on the way home.

Recognizing progression matters because it changes the kind of support someone needs. A person in early-stage dementia might just need reminders and occasional help with finances, but someone moving into the middle stages may need supervision throughout the day. This article walks through the specific cognitive, behavioral, and physical signs that indicate dementia is advancing, how to distinguish normal fluctuations from true decline, what to expect at each stage, and practical steps for caregivers who are watching someone they love slip further into the disease.

Table of Contents

- How Do You Know If Dementia Is Getting Worse Over Time?

- Cognitive Signs That Dementia Is Advancing Beyond Early Stages

- Behavioral and Personality Changes That Signal Progression

- What to Do When You Notice Signs of Worsening Dementia

- Physical Decline and Late-Stage Warning Signs

- How Fast Does Dementia Progress and What Affects the Speed

- When Progression Demands a Change in Care

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Do You Know If Dementia Is Getting Worse Over Time?

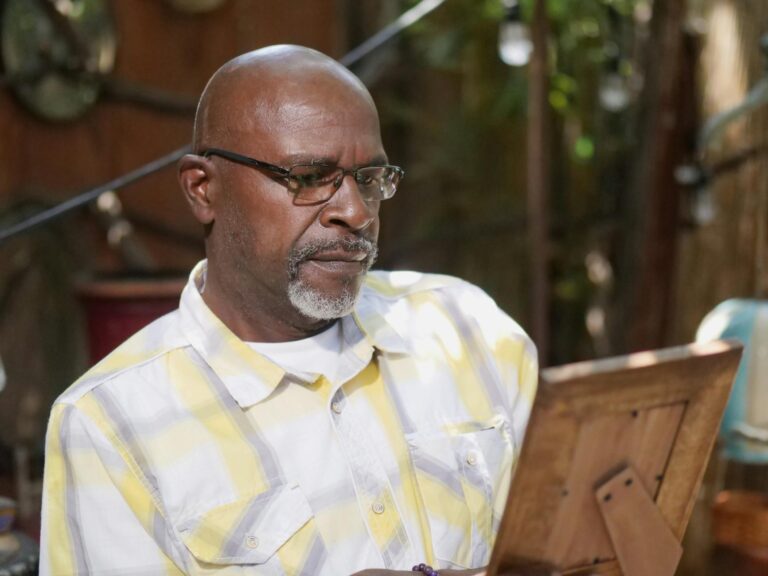

The clearest indicator that dementia is progressing is a sustained decline in someone’s ability to do things they could do three to six months ago. This is different from a bad day, which everyone with dementia has. True progression means the baseline has shifted. For example, a person who previously needed a reminder to take medications but could still manage the pill organizer may now be unable to open the organizer at all, or may take the wrong pills even with labels. The Alzheimer’s Association notes that the average duration from diagnosis to end of life is four to eight years, but some people live as long as twenty years, and the rate of decline varies enormously from person to person. One useful comparison is the difference between a bad week and a new normal.

If your father gets confused during a urinary tract infection and then returns to his previous level of functioning after treatment, that’s a temporary setback caused by a medical issue, not disease progression. But if he recovers from the infection and still can’t do things he could do before, the infection may have accelerated the underlying decline. Tracking specific abilities over time, rather than relying on general impressions, gives families and doctors a much clearer picture. Some caregivers keep a simple journal noting what the person can and cannot do each week, which becomes invaluable during medical appointments. Standardized tools like the Mini-Mental State Examination or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment can also track decline, but they capture only a snapshot. The person who scores the same on a cognitive test two visits in a row may still be functioning worse at home because these tests don’t measure things like judgment in real-world situations or the ability to handle unexpected problems.

Cognitive Signs That Dementia Is Advancing Beyond Early Stages

Memory loss in early dementia tends to affect recent events while leaving older memories relatively intact. As the disease advances, even long-term memories start to erode. A woman in the middle stages might not only forget what she had for breakfast but also struggle to remember the names of her grandchildren or the city where she grew up. Language problems become more pronounced too. Where she once searched for the right word occasionally, she may now substitute wrong words frequently, lose her train of thought mid-sentence, or stop talking altogether because the effort is too great. Executive function, the brain’s ability to plan, sequence, and problem-solve, deteriorates significantly. Tasks that require multiple steps become impossible without guidance.

Cooking is a common early casualty because it requires sequencing ingredients, managing timing, and adjusting to unexpected situations like a missing ingredient. However, if someone suddenly loses an ability they had just days ago, that rapid change is usually not dementia progression alone. Sudden cognitive drops warrant immediate medical evaluation because they often signal a stroke, infection, medication reaction, or delirium, all of which are potentially treatable. Families sometimes assume every decline is “just the dementia” and miss conditions that could be reversed. Spatial awareness and visual processing also decline. A person may misjudge distances, have trouble navigating familiar hallways, or fail to recognize objects for what they are. This is particularly dangerous around stairs, in bathrooms, and in parking lots.

Behavioral and Personality Changes That Signal Progression

One of the most distressing signs for families is when someone’s personality seems to change. A previously calm and gentle person may become agitated, suspicious, or verbally aggressive. A lifelong introvert may become disinhibited, making inappropriate comments in public. These changes are not the person being difficult. They are the result of damage to brain regions that regulate emotion, social behavior, and impulse control. In frontotemporal dementia, personality changes often appear before significant memory loss, but in Alzheimer’s disease, they typically emerge in the middle stages. Paranoia and delusions become more common as dementia progresses.

A man might accuse his wife of stealing his wallet when he simply cannot remember where he put it. He might believe strangers are entering the house at night or that a caregiver is trying to poison him. These beliefs feel absolutely real to the person experiencing them, and arguing or trying to correct the delusion usually makes things worse. Sundowning, a pattern of increased confusion and agitation in the late afternoon and evening, also tends to intensify as the disease advances. Withdrawal from social activities is another marker. Someone who loved weekly card games may stop attending, not because they lost interest but because they can no longer follow the rules or keep up with the conversation. The frustration of not being able to participate as they once did leads many people with progressing dementia to pull back from the activities that once gave their life structure and meaning.

What to Do When You Notice Signs of Worsening Dementia

When you see consistent signs of decline, the first step is a medical evaluation to rule out treatable causes. Depression, thyroid problems, vitamin B12 deficiency, urinary tract infections, medication side effects, and dehydration can all mimic or accelerate dementia symptoms. Addressing these issues won’t reverse the underlying disease, but it can restore some lost function and slow the apparent decline. A thorough medication review is especially important because people with dementia are often on multiple prescriptions, and drugs with anticholinergic properties like certain antihistamines and bladder medications can significantly worsen cognition. The tradeoff families face at this point is between maintaining independence and ensuring safety. Allowing someone to keep doing things for themselves preserves dignity and may slow functional decline, but it also introduces risks.

Letting someone continue to cook means they might leave the stove on. Letting them walk outside alone means they might get lost. There is no universal right answer. The balance depends on the specific risks in the person’s environment, the severity of their impairment, and the level of supervision available. Some families install stove auto-shutoff devices, GPS trackers, and door alarms as intermediate measures that preserve some autonomy while reducing danger. Advance care planning, if it hasn’t already happened, becomes urgent when dementia begins to worsen. Decisions about finances, medical care, driving, and eventual living arrangements are far easier to navigate when the person with dementia can still participate in the conversation, even in a limited way.

Physical Decline and Late-Stage Warning Signs

Dementia is ultimately a disease of the brain, and as it advances, it affects the body’s basic functions. Walking becomes unsteady, and falls increase. Swallowing difficulties emerge, raising the risk of choking and aspiration pneumonia, which is one of the leading causes of death in people with advanced dementia. Incontinence develops as the brain loses the ability to recognize and respond to bladder and bowel signals. Weight loss is common even when food is offered regularly, partly because the person may forget to chew or swallow, and partly because the brain’s ability to regulate appetite deteriorates.

Families should be cautious about interpreting physical decline as a sign that nothing more can be done. Even in late-stage dementia, comfort-focused care makes a significant difference. Pain management, skin care to prevent pressure sores, gentle repositioning, mouth care, and simply being present with the person all matter. However, families should also understand that aggressive medical interventions like hospitalizations, feeding tubes, and repeated courses of antibiotics often cause more suffering than benefit in late-stage dementia. Research consistently shows that feeding tubes do not extend life or improve quality of life in advanced dementia, yet they are still sometimes recommended. Having these conversations with a palliative care team before a crisis occurs gives families time to make thoughtful decisions rather than reactive ones.

How Fast Does Dementia Progress and What Affects the Speed

The speed of progression depends on several factors: the type of dementia, the person’s age at diagnosis, their overall health, and genetic factors that are not yet fully understood. Vascular dementia, caused by reduced blood flow to the brain, sometimes progresses in a stepwise pattern with periods of stability followed by sudden drops, often corresponding to small strokes. Alzheimer’s disease tends to follow a more gradual downward slope.

Lewy body dementia can fluctuate dramatically from day to day, making it harder to assess whether the overall trajectory is worsening. A seventy-year-old diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer’s who also has well-managed blood pressure and stays physically and socially active may decline more slowly than an eighty-five-year-old with diabetes, heart disease, and limited social contact. Managing cardiovascular risk factors, maintaining physical activity to whatever degree is possible, treating hearing and vision loss, and keeping the person socially engaged won’t stop dementia, but evidence suggests these interventions can modestly slow functional decline.

When Progression Demands a Change in Care

At some point, most families reach a threshold where the current care arrangement is no longer safe or sustainable. This might mean transitioning from independent living to an assisted living facility, moving a parent into the family home, or shifting from assisted living to a memory care unit. The decision is rarely clear-cut, and guilt is almost universal.

Looking ahead, research into blood-based biomarkers and digital monitoring tools may eventually allow clinicians to track dementia progression more precisely and intervene earlier when decline accelerates. For now, the most reliable indicators of worsening remain what caregivers observe day to day: the gradual erosion of abilities, the emergence of new behavioral symptoms, and the increasing gap between what the person can do and what they need to do to remain safe. Paying attention to these changes, documenting them, and communicating them to the medical team is one of the most important things a caregiver can do.

Conclusion

Worsening dementia reveals itself through a constellation of changes: deepening memory loss, declining ability to perform everyday tasks, emerging behavioral symptoms like agitation or paranoia, and eventually physical deterioration including difficulty walking, swallowing, and maintaining continence. Not every bad day means the disease has progressed, but a sustained pattern of lost abilities over weeks or months signals that the care plan needs to be reassessed. Ruling out treatable causes of decline, adjusting medications, and updating safety measures at home are concrete steps that can make a real difference even when the underlying disease cannot be reversed.

Caring for someone whose dementia is getting worse is one of the hardest things a person can do, and it does not come with a manual. Building a support team that includes a knowledgeable physician, a social worker, other family members, and respite care providers is not optional but essential for sustainable caregiving. The goal shifts over time from maintaining independence to ensuring comfort, and recognizing where someone falls on that continuum helps families make decisions that honor both the person’s safety and their dignity.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between normal aging memory loss and worsening dementia?

Normal aging might cause you to forget where you put your keys. Worsening dementia means forgetting what keys are for, or not recognizing that you need keys to open a door. The distinction is between occasional retrieval failures and a fundamental breakdown in how the brain processes and uses information.

Can dementia get worse suddenly overnight?

A sudden dramatic decline is usually not dementia progression itself but rather a superimposed condition like a urinary tract infection, delirium from a new medication, a stroke, or severe constipation. These causes should be evaluated immediately because many are reversible.

How long does each stage of dementia typically last?

Early-stage dementia may last two to four years, the middle stage often lasts two to ten years and is usually the longest, and late-stage dementia typically lasts one to three years. These ranges vary widely depending on dementia type, age, and overall health.

Should I tell the person with dementia that they are getting worse?

This depends on the individual and the stage of disease. In early stages, many people are aware of their decline and may want honest information to help them plan. In later stages, the person may lack the capacity to understand or retain this information, and telling them may cause unnecessary distress without any practical benefit.

Does dementia always get worse, or can it stabilize?

Most forms of dementia are progressive and will worsen over time. However, the rate of decline varies and some people experience long plateaus where abilities remain relatively stable. Addressing contributing factors like depression, poor sleep, or medication side effects can sometimes restore function that appeared to be permanently lost.