Vascular dementia life expectancy after a major stroke is generally shorter than many families expect. Research consistently shows that the average survival time following a diagnosis of vascular dementia is roughly three to five years, though some patients live longer and others decline much faster. When vascular dementia develops specifically after a major stroke — as opposed to accumulating through smaller, silent strokes over time — the prognosis tends to fall toward the lower end of that range, particularly if the stroke caused extensive brain damage or if the person already had significant cardiovascular disease. A 74-year-old man who suffers a large middle cerebral artery stroke and is subsequently diagnosed with vascular dementia, for instance, might realistically face a life expectancy of two to four years, depending on his overall health, the quality of post-stroke rehabilitation, and whether further strokes can be prevented.

Several factors make post-stroke vascular dementia different from other forms of cognitive decline. Unlike Alzheimer’s disease, which follows a relatively predictable slow decline, vascular dementia often progresses in a stepwise pattern — periods of relative stability interrupted by sudden drops, frequently tied to additional vascular events. After a major stroke, the brain has already sustained catastrophic damage, and the same underlying vascular disease that caused the stroke remains an ongoing threat. This article covers what the research actually says about survival timelines, which factors shorten or extend life expectancy, how post-stroke vascular dementia compares to other dementia types, and what families can realistically do to improve outcomes.

Table of Contents

- How Long Can Someone Live with Vascular Dementia After a Major Stroke?

- Why Vascular Dementia After a Stroke Progresses Differently Than Alzheimer’s

- The Role of Stroke Location and Severity in Determining Prognosis

- What Families Can Do to Extend Life and Maintain Quality of Life

- Common Complications That Shorten Life Expectancy in Post-Stroke Vascular Dementia

- How Post-Stroke Vascular Dementia Compares to Mixed Dementia

- Advances in Post-Stroke Dementia Research and What They Mean for Families

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Long Can Someone Live with Vascular Dementia After a Major Stroke?

The honest answer is that survival varies enormously, and no doctor can give a precise number. A 2015 study published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease found that median survival after a vascular dementia diagnosis was approximately 3.3 years, compared to about 5.7 years for Alzheimer’s disease. However, that figure includes all forms of vascular dementia — people with slow, cumulative small vessel disease as well as those who developed dementia after a single catastrophic stroke. When researchers look specifically at post-stroke dementia, the numbers tend to be grimmer. A large Danish registry study found that patients diagnosed with dementia within three months of a stroke had roughly double the mortality risk compared to stroke survivors who did not develop dementia. Age at the time of the stroke matters significantly.

A person who has a major stroke and develops vascular dementia at age 65 will, on average, survive longer than someone who experiences the same at age 82 — not only because younger patients tend to have more physiological reserve, but because they are less likely to have multiple comorbidities stacking the odds against them. The severity of the stroke itself is also critical. A stroke that destroys tissue in areas controlling basic functions like swallowing or breathing creates immediate risks that go beyond cognition. Aspiration pneumonia, for example, is one of the leading causes of death in post-stroke dementia patients, and it stems directly from the physical damage the stroke inflicts on the brainstem or motor pathways. It is worth noting that some patients defy the averages entirely. Individuals who receive aggressive secondary prevention — blood pressure management, anticoagulation if atrial fibrillation is present, statin therapy, and lifestyle modifications — can stabilize for years without a second major vascular event. The averages are shaped heavily by patients who experience recurrent strokes, and anything that reduces that recurrence risk can meaningfully shift the timeline.

Why Vascular Dementia After a Stroke Progresses Differently Than Alzheimer’s

One of the most disorienting things for families is that vascular dementia does not follow the gradual, steady decline they may have read about in Alzheimer’s literature. Instead, the trajectory after a major stroke often looks like a staircase going down — the person may remain relatively stable for weeks or months, then suddenly lose additional function after a transient ischemic attack or another small stroke. This stepwise pattern means that caregivers can be lulled into a false sense of stability, only to face a sudden and frightening deterioration. However, if the underlying vascular risk factors are well controlled and no further strokes occur, some patients experience a plateau that can last a year or more. This is genuinely different from Alzheimer’s, where the neurodegenerative process continues regardless of what medications are prescribed.

In vascular dementia, the brain damage that has already occurred is largely permanent, but future damage is at least partially preventable. This is both the hopeful and the frustrating part of the diagnosis — the disease is theoretically more controllable than Alzheimer’s, but only if the cardiovascular system cooperates. The limitation families need to understand is that “stable” in vascular dementia does not mean “recovering.” The cognitive deficits caused by the stroke are usually permanent. What stability means is that no new damage is accumulating. If a family member seems to be improving in the months after a stroke, that likely reflects the brain’s natural recovery from the acute event — swelling resolving, surviving neurons compensating — rather than the dementia itself reversing. Once that recovery window closes, typically within six to twelve months, the cognitive baseline that remains is generally the new reality.

The Role of Stroke Location and Severity in Determining Prognosis

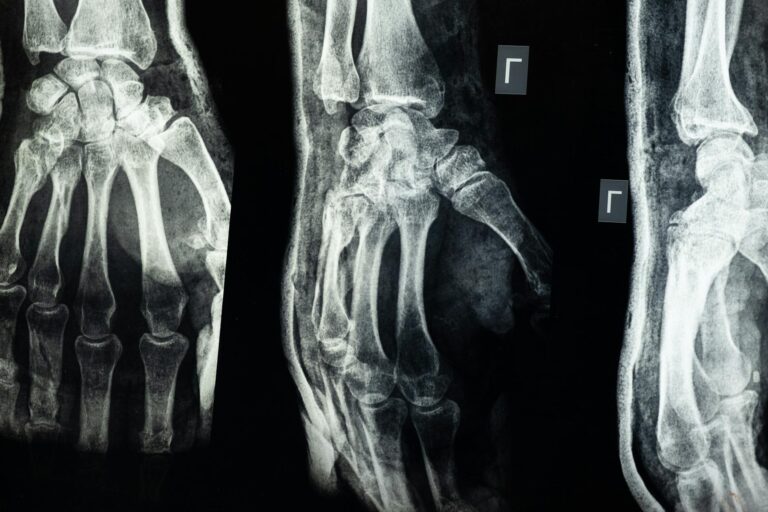

Not all major strokes carry the same dementia risk or the same life expectancy implications. A large stroke in the left middle cerebral artery territory, which often devastates language and motor function on the right side of the body, creates a very different clinical picture than a posterior circulation stroke affecting the brainstem and cerebellum. Location determines which cognitive domains are affected, which physical disabilities result, and which complications are most likely to arise. Strokes that affect the thalamus or the deep white matter tracts connecting different brain regions tend to produce particularly severe cognitive impairment relative to their size. A relatively small thalamic stroke can cause profound memory deficits and apathy that look very much like advanced Alzheimer’s disease, while a larger cortical stroke might leave memory intact but destroy the ability to plan, organize, or make decisions.

For life expectancy specifically, strokes that impair swallowing — common in brainstem and large hemispheric strokes — carry the worst prognosis, because aspiration pneumonia becomes a recurring and eventually fatal threat. One study in the journal Stroke found that dysphagia after a major stroke increased mortality risk by roughly 30 percent over the following year. Bilateral strokes, where both hemispheres sustain significant damage either simultaneously or sequentially, are associated with the steepest cognitive decline and shortest survival. A person who suffers a major right-sided stroke and then, six months later, a significant left-sided stroke is facing a fundamentally different situation than someone with damage confined to one hemisphere. The brain’s ability to compensate depends on having healthy tissue to take over lost functions, and bilateral damage severely limits that capacity.

What Families Can Do to Extend Life and Maintain Quality of Life

The most impactful thing families can do is focus relentlessly on preventing the next stroke. This sounds obvious, but in practice it requires sustained attention to unglamorous medical management — making sure blood pressure medications are taken consistently, ensuring atrial fibrillation is properly anticoagulated, managing diabetes tightly, and eliminating smoking. Each of these interventions has strong evidence behind it. A well-managed blood pressure regimen alone can reduce the risk of recurrent stroke by 25 to 30 percent, which in the context of vascular dementia translates directly to a lower risk of further cognitive decline. There is a genuine tradeoff, however, between aggressive medical management and quality of life.

A patient with advanced vascular dementia who is taking eight or ten medications may experience side effects — dizziness from blood pressure drugs, bleeding risk from anticoagulants, gastrointestinal problems from statins — that meaningfully reduce their daily comfort. At some point, families and physicians need to have an honest conversation about goals of care. For a patient in the early stages after a major stroke, aggressive prevention makes clear sense. For a patient who is already severely impaired and bedridden several years later, the calculus may shift toward comfort and symptom management rather than maximum stroke prevention. Physical rehabilitation and cognitive engagement also matter, though their effects on life expectancy per se are harder to quantify. What is clear is that patients who receive structured rehabilitation after a stroke — physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy where appropriate — tend to maintain functional independence longer, which in turn reduces the risks associated with immobility: blood clots, pressure ulcers, pneumonia, and the general deconditioning that accelerates decline.

Common Complications That Shorten Life Expectancy in Post-Stroke Vascular Dementia

The leading causes of death in vascular dementia patients are not the dementia itself but the complications that arise from both the underlying vascular disease and the physical disabilities imposed by stroke. Recurrent stroke is the single biggest killer, accounting for a substantial proportion of deaths in this population. Pneumonia — often aspiration pneumonia caused by swallowing difficulties — is the second major threat. Heart disease, including heart attacks and heart failure, ranks close behind, which makes sense given that the same atherosclerotic processes that damage brain blood vessels also damage coronary arteries. Falls represent an underappreciated danger. Post-stroke patients often have hemiparesis or balance problems, and when you layer cognitive impairment on top of that — poor judgment, spatial disorientation, impulsivity — the risk of serious falls increases dramatically.

A hip fracture in an 80-year-old with vascular dementia carries a mortality rate of roughly 30 percent within the following year. Families should be warned that fall prevention is not just about removing throw rugs and installing grab bars, though those help. It also means honestly assessing whether the person can safely navigate their environment and being willing to increase supervision or modify the living situation even when the patient resists. Infections beyond pneumonia also pose significant risk. Urinary tract infections are common in patients with limited mobility or incontinence, and in elderly patients with dementia, a UTI can trigger delirium that compounds existing cognitive deficits. What begins as a treatable infection can cascade into hospitalization, further immobility, and accelerated decline. The warning for families is that any acute change in behavior or cognition in a vascular dementia patient — increased confusion, agitation, sudden lethargy — should prompt a medical evaluation for infection rather than being attributed solely to the dementia progressing.

How Post-Stroke Vascular Dementia Compares to Mixed Dementia

Many patients diagnosed with vascular dementia after a stroke actually have mixed dementia — a combination of vascular damage and underlying Alzheimer’s pathology. Autopsy studies have shown that pure vascular dementia, without any coexisting Alzheimer’s changes, is less common than once thought. A patient who appeared cognitively normal before a stroke may in fact have had early, undiagnosed Alzheimer’s disease that the stroke unmasked.

In these mixed cases, life expectancy tends to be shorter than in either pure vascular dementia or pure Alzheimer’s alone, because the brain is being attacked on two fronts. This matters practically because the management strategies differ. If a patient with post-stroke dementia also has an Alzheimer’s component, cholinesterase inhibitors like donepezil may offer modest benefit — something that has not been convincingly demonstrated for pure vascular dementia. Families should ask the diagnosing neurologist whether mixed pathology is suspected and whether Alzheimer’s-specific treatments are worth trying.

Advances in Post-Stroke Dementia Research and What They Mean for Families

Research into vascular dementia has historically lagged behind Alzheimer’s research, but that is slowly changing. Recent large-scale studies are focusing on whether aggressive risk factor management initiated immediately after a stroke can prevent the development of dementia in the first place, rather than merely slowing its progression after it has set in. The PODCAST trial and several ongoing European studies are examining whether intensive blood pressure lowering, combined with targeted cognitive rehabilitation, can reduce post-stroke dementia incidence by a meaningful margin.

There is also growing interest in neuroimaging biomarkers that could help predict which stroke patients are at highest risk for developing dementia, allowing for earlier and more targeted intervention. White matter hyperintensity burden on MRI, for example, correlates with future cognitive decline and could eventually be used to stratify patients into different risk categories immediately after their stroke. For families navigating this diagnosis now, the practical takeaway is that the field is moving toward earlier identification and prevention, which means pushing for thorough neurological follow-up after any major stroke rather than waiting for cognitive problems to become obvious.

Conclusion

Vascular dementia after a major stroke carries a serious prognosis, with average survival typically ranging from two to five years depending on age, stroke severity, comorbidities, and the success of secondary prevention efforts. The stepwise nature of the disease means that the trajectory is less predictable than other dementias — a patient may remain stable for extended periods or decline suddenly with a recurrent vascular event. The most important modifiable factor is preventing additional strokes through consistent medical management and lifestyle changes.

Complications like aspiration pneumonia, falls, and infections represent the proximate causes of death in many cases, and proactive attention to these risks can extend both life and quality of life. Families facing this diagnosis should focus on what they can control: medication adherence, rehabilitation participation, fall prevention, and regular medical follow-up. They should also prepare for the reality that vascular dementia is a terminal condition and begin conversations about goals of care early, while the patient may still be able to participate in those decisions. Palliative care involvement does not mean giving up — it means ensuring that the focus remains on comfort and dignity alongside medical management, which is exactly what most patients would want if asked.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can vascular dementia be reversed after a stroke?

No. The brain tissue destroyed by a stroke does not regenerate. Some functional improvement may occur in the months following a stroke as swelling resolves and surviving brain areas compensate, but this represents recovery from the acute event, not reversal of the dementia itself. The goal of treatment is to prevent further damage, not to undo what has already occurred.

Is vascular dementia after a stroke worse than Alzheimer’s disease?

They are different rather than strictly comparable. Vascular dementia after a stroke tends to have a shorter average survival than Alzheimer’s, partly because of the ongoing risk of recurrent strokes and the physical disabilities that accompany them. However, vascular dementia progression can potentially be slowed or stabilized by controlling cardiovascular risk factors, which is not the case with Alzheimer’s.

How quickly does vascular dementia progress after a major stroke?

Progression is unpredictable and depends heavily on whether further vascular events occur. Some patients remain at a stable cognitive level for a year or more. Others experience rapid decline, particularly if they suffer additional strokes. The stepwise pattern — periods of stability interrupted by sudden drops — is characteristic but not universal.

Does the size of the stroke determine how long someone will live with vascular dementia?

Stroke size is one factor, but location and the resulting functional impairments matter just as much. A moderate-sized stroke in a critical area like the brainstem, which can impair swallowing and breathing, may carry a worse prognosis than a larger stroke in a less functionally critical region. The overall burden of vascular disease throughout the brain is also important.

Should someone with vascular dementia after a stroke be placed in a care facility?

This depends on the severity of both the cognitive and physical impairments, the availability of home caregivers, and the safety of the home environment. Many patients can be managed at home in the early stages with appropriate support, but as the disease progresses and care needs intensify, residential care may become necessary to ensure safety and adequate supervision, particularly if swallowing difficulties or fall risk are significant.