A traumatic brain injury does not end when the bruises heal. Research now shows that even a single TBI raises the long-term risk of dementia by roughly 24 percent compared to people who have never sustained a head injury, and moderate-to-severe injuries can double to quadruple that risk. A January 2026 study published in JAMA Network Open, drawing on Framingham Heart Study data collected over seven decades, found that TBI is linked to higher all-cause mortality largely because it drives dementia-related deaths rather than deaths from other causes. For someone who suffers a concussion in a car accident at age 25, this means the consequences may not surface for decades, potentially manifesting as cognitive decline in their 50s.

The connection between head trauma and later neurodegeneration has been suspected for over a century, dating back to the “punch-drunk” syndrome described in boxers. But only in the last several years has the science sharpened enough to quantify the risk with confidence, identify biological mechanisms, and distinguish between single injuries and cumulative damage. A meta-analysis published in Neuroepidemiology calculated a pooled odds ratio of 1.81, meaning TBI nearly doubles dementia risk across the studied populations. This article covers the dose-response relationship between injury severity and dementia, the compounding danger of repeated head trauma, newly discovered biological pathways including tau protein accumulation and viral reactivation, the ongoing reckoning with chronic traumatic encephalopathy in contact sports, and what individuals and families can do with this information.

Table of Contents

- How Much Does a Single Traumatic Brain Injury Raise Your Dementia Risk?

- The Compounding Danger of Repeated Head Injuries

- What Happens Inside the Brain After Injury

- CTE and Contact Sports: What the Evidence Actually Shows

- Age, Timing, and Who Is Most Vulnerable

- How Large Is the Public Health Burden?

- Where the Science Is Heading

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Much Does a Single Traumatic Brain Injury Raise Your Dementia Risk?

The answer depends on severity, but the short version is that no TBI is truly harmless in the long run. According to research from the University of Washington, moderate-to-severe TBI increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias by two to four times. Even mild TBI, the category that includes most concussions, increases dementia-related mortality risk by 60 percent, based on the January 2026 JAMA Network Open study. Moderate-to-severe injuries carry a more than threefold increase in dementia-related mortality. What makes these numbers particularly sobering is the latency.

The University of Washington research found that a TBI sustained in your 20s can increase the risk of developing dementia in your 50s by 60 percent. That is a gap of three decades between injury and clinical consequence, which means many people never connect the two events. A college athlete who takes a hard hit during a football game may not think about it again until memory problems appear decades later, and by then, the window for early intervention has narrowed considerably. It is worth noting a limitation in this data: most large studies rely on hospital records or insurance claims to identify TBI, which means mild injuries that were never medically evaluated are likely underrepresented. The true population-level risk may be higher than current estimates suggest, particularly for mild TBI, because so many concussions go unreported.

The Compounding Danger of Repeated Head Injuries

One head injury is concerning. Multiple injuries are dramatically worse, and the relationship is not simply additive. Data from the University of Washington demonstrates a clear dose-response curve: two to three TBIs carry a 33 percent higher dementia risk, four TBIs raise it to 61 percent, and five or more TBIs push the risk up by 183 percent. Each additional injury appears to erode the brain’s resilience further, reducing its ability to compensate for accumulating damage. This has obvious implications for athletes in contact sports, military personnel exposed to blast injuries, and survivors of domestic violence who may sustain repeated blows to the head over months or years. However, the risk is not limited to dramatic impacts.

Researchers now recognize that repeated sub-concussive hits, impacts that do not produce symptoms severe enough to be diagnosed as concussions, are a major driver of long-term brain pathology. An offensive lineman in football may never receive a concussion diagnosis yet absorb thousands of sub-concussive impacts over a career. Research from the NIH found that every 1,000 additional blows to the head confers a 21 percent increased odds of CTE diagnosis and a 13 percent increased odds of severe CTE. There is an important caveat here: if someone has sustained multiple mild TBIs but experiences no current cognitive symptoms, that does not guarantee safety. The pathological changes may already be underway at a cellular level, visible only on specialized imaging or, in the case of CTE, through post-mortem autopsy. Conversely, a single severe TBI in an individual with strong cognitive reserve and no genetic predispositions may not lead to dementia at all. Risk is probabilistic, not deterministic, and individual trajectories vary widely.

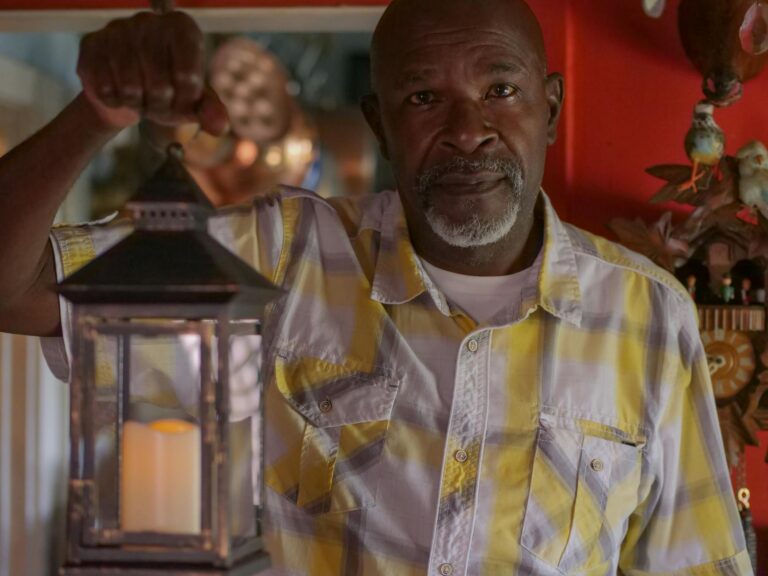

What Happens Inside the Brain After Injury

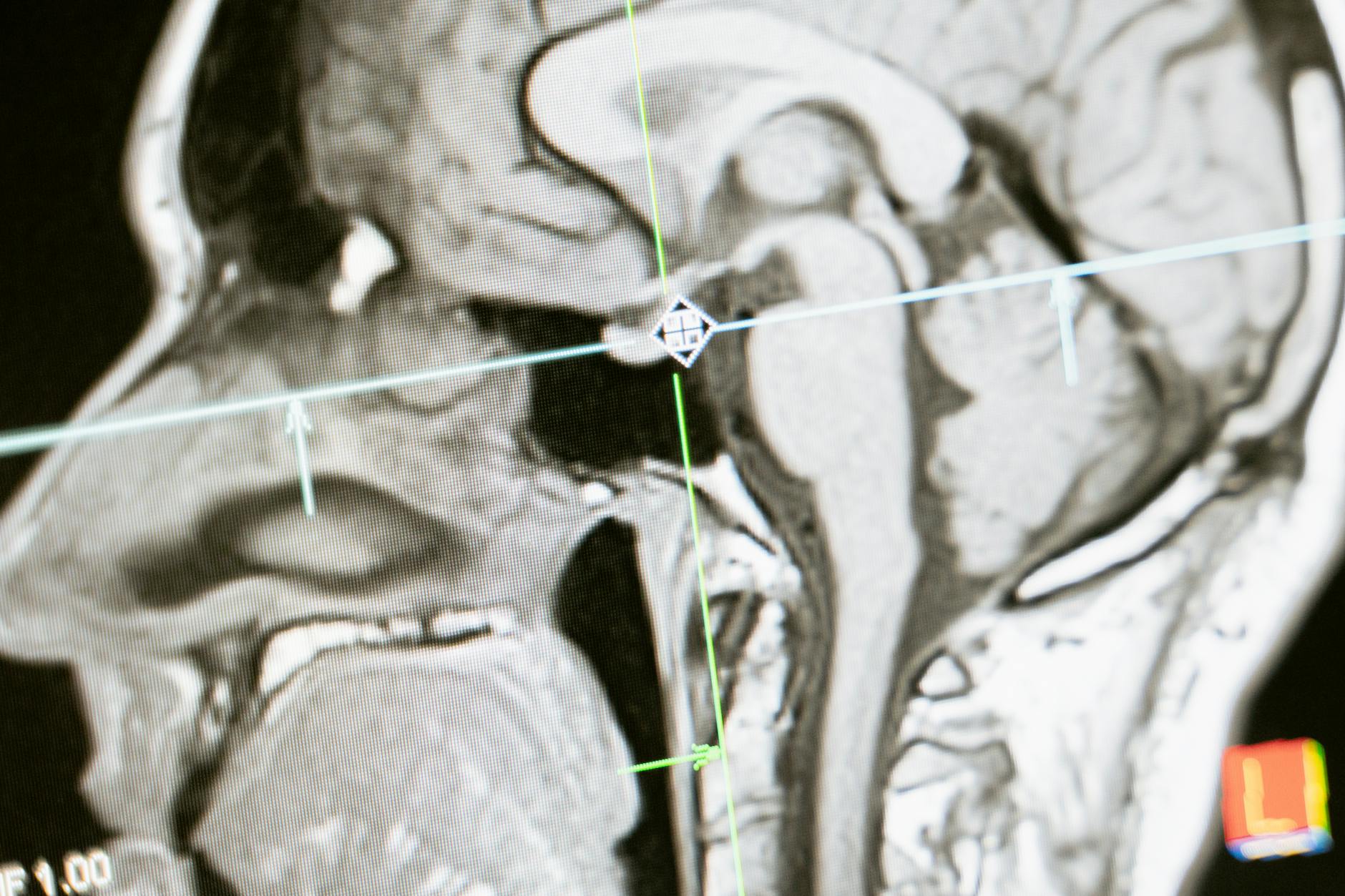

Recent research has begun to reveal why head injuries create such fertile ground for neurodegeneration, and the mechanisms are more complex than simple physical damage to neurons. Three biological pathways have attracted significant scientific attention in the past two years. The first involves tau protein, one of the hallmark features of Alzheimer’s disease. Research from the University of Virginia has shown that even a single mild TBI can accelerate harmful tau accumulation in the brain. Under normal conditions, tau helps stabilize the internal scaffolding of neurons. After injury, tau can become misfolded and begin clumping into tangles that disrupt cell function and eventually kill neurons.

This process may begin immediately after injury but take years or decades to produce noticeable cognitive symptoms. MRI studies from USC have reinforced this connection, showing that gray and white matter degrade in strikingly similar patterns in both TBI patients and Alzheimer’s patients, suggesting shared downstream pathology. The second pathway, published in January 2025 by researchers at the University of Oxford, involves viral reactivation. The study found that repeated head injuries may reactivate dormant herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) in the brain, triggering inflammatory cascades resembling those seen in Alzheimer’s disease. HSV-1 is extremely common, with an estimated two-thirds of the global population carrying it, usually without symptoms. The possibility that mechanical brain trauma could awaken a dormant virus and set off neuroinflammation opens an entirely new avenue of research and, potentially, treatment. If viral reactivation proves to be a significant driver, antiviral medications could theoretically become part of post-TBI care, though this remains speculative.

CTE and Contact Sports: What the Evidence Actually Shows

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy has become one of the most publicly visible consequences of repeated head trauma, largely because of high-profile cases in professional football. The numbers are stark: of 376 autopsied NFL player brains examined in a landmark study published in Science, 345 of them, or 91.8 percent, showed evidence of CTE. That figure demands context, however, because the brains studied were donated by families who already suspected neurological problems, creating a significant selection bias. The true prevalence of CTE among all former NFL players remains unknown. What is well established is that CTE is a progressive disease characterized by abnormal tau deposits, and that it is strongly associated with repetitive head impacts rather than a single catastrophic injury. The condition can cause mood disturbances, impulsivity, memory loss, and eventually severe dementia.

One of the most frustrating aspects of CTE is that it cannot currently be diagnosed in living persons. Diagnosis requires post-mortem autopsy, meaning that affected individuals cannot receive a definitive answer during their lifetimes, and researchers cannot study the disease’s progression in real time. Efforts are underway to develop blood-based biomarkers and advanced PET imaging techniques that might detect CTE pathology in living brains, but none have been validated for clinical use. The CTE conversation has expanded beyond football. Soccer players, hockey players, rugby athletes, and military veterans are all recognized as at-risk populations. For families navigating these risks, the practical question is often not whether to avoid contact sports entirely but how to minimize cumulative exposure, enforce proper recovery protocols after concussions, and stay informed about emerging diagnostic tools.

Age, Timing, and Who Is Most Vulnerable

One finding that surprises many people is that older adults, not young athletes, represent the largest population sustaining traumatic brain injuries. The Framingham Heart Study data, published in January 2026, found that the mean age at first TBI among participants was in the early-to-mid 70s, and falls were the leading cause. This is consistent with broader epidemiological data: as populations age, fall-related TBIs are becoming a growing public health concern, particularly because older brains are already contending with age-related changes that reduce resilience. The timing of a TBI relative to a person’s age appears to matter for the type and severity of dementia risk.

Younger individuals who sustain TBI face an elevated risk that may not manifest for decades, as noted in the University of Washington research linking injuries in the 20s to dementia onset in the 50s. Older adults who sustain TBI face a more immediate threat, with the Framingham data showing that TBI in later life is associated with accelerated progression to dementia-related death. A key limitation across all these studies is the difficulty of separating pre-existing cognitive vulnerability from TBI-caused decline, especially in elderly patients who may have had undiagnosed early-stage neurodegeneration before their injury. A December 2025 study using Welsh population health records examined dementia risk by subtype following TBI and confirmed that head injury is a significant risk factor not just for Alzheimer’s disease but across multiple dementia subtypes. This broadens the concern beyond the traditional focus on Alzheimer’s and suggests that TBI may trigger or accelerate several distinct neurodegenerative pathways.

How Large Is the Public Health Burden?

Estimates suggest that TBI accounts for somewhere between 5 and 15 percent of all dementia cases at the population level. That range may sound modest, but given that over 55 million people worldwide live with dementia, even the lower bound represents millions of cases that might have been prevented or delayed if the initial brain injuries had been avoided or better managed. Consider the practical implications: a construction worker who sustains several concussions over a career, a high school football player who returns to play too quickly after a head impact, an elderly person whose home lacks fall-prevention modifications.

Each of these scenarios represents a potentially preventable contribution to the global dementia burden. Unlike genetic risk factors, TBI is modifiable. Helmets, workplace safety regulations, fall-prevention programs for older adults, and rule changes in contact sports all have the potential to reduce the incidence of TBI and, by extension, some fraction of future dementia cases.

Where the Science Is Heading

The next several years are likely to bring significant advances in both understanding and managing TBI-related dementia risk. Blood-based biomarkers are a major area of active research, with the goal of identifying individuals whose brains are already undergoing pathological changes long before symptoms appear. If validated, these biomarkers could allow clinicians to flag high-risk patients after a TBI and begin neuroprotective interventions early.

The viral reactivation pathway discovered by Oxford researchers also opens intriguing therapeutic possibilities. If dormant HSV-1 reactivation proves to be a meaningful contributor to post-TBI neurodegeneration, antiviral treatments could potentially become part of standard post-injury care. Meanwhile, advances in tau-targeted therapies, including immunotherapies designed to clear abnormal tau from the brain, are progressing through clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease and may eventually be studied in TBI populations. None of these approaches is ready for clinical application today, but the pace of discovery has accelerated markedly, and the recognition that TBI is a modifiable risk factor for dementia has brought new funding and urgency to the field.

Conclusion

The evidence linking traumatic brain injury to long-term dementia risk is no longer preliminary or ambiguous. A single mild TBI raises dementia-related mortality risk by 60 percent. Moderate-to-severe injuries triple it. Repeated injuries compound the danger in a steep dose-response curve, and the biological mechanisms, from tau accumulation to viral reactivation to structural brain degradation, are increasingly well understood. The January 2026 Framingham Heart Study data reinforced what decades of research have been building toward: TBI does not just cause acute injury.

It sets in motion a slow cascade that, for many people, ends in dementia. For individuals and families, the practical takeaways are straightforward even if the science is complex. Prevent head injuries where possible through fall-proofing homes for older adults, wearing appropriate protective equipment, and taking concussions seriously rather than dismissing them. After any TBI, follow medical guidance on rest and recovery. For those with a history of multiple head injuries, discuss cognitive monitoring with a physician. And for anyone caring for a loved one who sustained a TBI years or decades ago and is now showing signs of cognitive decline, understand that the connection is real, recognized by the medical community, and increasingly supported by actionable research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a single concussion cause dementia?

A single mild TBI does increase long-term dementia risk, though the increase is smaller than with repeated injuries. Research published in JAMA Network Open in January 2026 found that even mild TBI raises dementia-related mortality risk by 60 percent. However, many people who sustain a single concussion never develop dementia. The risk is elevated, not guaranteed.

How long after a TBI can dementia develop?

The latency period can be decades. University of Washington research found that a TBI sustained in one’s 20s can increase dementia risk in the 50s. In older adults, the progression can be faster. There is no fixed timeline, and individual factors such as genetics, overall health, and subsequent injuries all influence the trajectory.

Is CTE the same as dementia?

CTE is a specific neurodegenerative disease caused by repeated head impacts, characterized by abnormal tau protein deposits. It can cause dementia-like symptoms including memory loss, confusion, and personality changes, but it is a distinct condition. Importantly, CTE can currently only be diagnosed through post-mortem autopsy, not in living patients.

Are sub-concussive hits dangerous?

Yes. Research from the NIH has shown that cumulative sub-concussive impacts, hits that do not cause diagnosable concussion symptoms, are a major driver of CTE pathology. Every 1,000 additional blows to the head confer a 21 percent increased odds of CTE diagnosis. The absence of concussion symptoms does not mean the brain is unharmed.

Does wearing a helmet prevent TBI-related dementia risk?

Helmets reduce the risk and severity of TBI in many scenarios, particularly in cycling, construction, and military contexts. However, they do not eliminate the risk entirely, especially for rotational forces that can cause diffuse brain injury. In contact sports like football, helmets reduce skull fractures and severe focal injuries but do not fully prevent the repetitive sub-concussive impacts associated with CTE.

What should I do if I have a history of multiple head injuries?

Speak with a neurologist or your primary care physician about cognitive baseline testing and ongoing monitoring. Maintaining cardiovascular health, staying mentally and socially active, managing sleep and stress, and avoiding further head injuries are all evidence-supported strategies for protecting long-term brain health. Early detection of cognitive changes allows for earlier intervention and planning.