Memantine is effective for moderate to severe dementia, and the evidence supporting that conclusion is both substantial and consistent. Approved by the FDA in 2003 specifically for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease — making it the first drug ever approved for that stage of the condition — memantine has been studied in thousands of patients across dozens of randomized controlled trials. A Cochrane review drawing on approximately 14 studies and 3,700 participants found statistically significant benefits over placebo in cognition, daily functioning, behavior and mood, and overall clinical ratings. The improvements are real, though they are modest in magnitude and do not halt the disease.

To put that in practical terms: a person with moderate Alzheimer’s who is struggling with basic daily tasks like dressing, meal preparation, and recognizing family members may show slower decline in those abilities while taking memantine compared to a person on placebo. The drug does not reverse the damage already done, and it is not a cure. What it does, in many cases, is slow the rate at which function deteriorates — a meaningful outcome for caregivers and families managing day-to-day care. This article covers how memantine works, what the clinical trials actually show, how it compares with other drugs, its safety profile, and what a newer 2025 meta-analysis found about an unexpected benefit: reduced mortality.

Table of Contents

- How Does Memantine Work in Moderate to Severe Dementia?

- What Do Clinical Trials Show About Memantine’s Effectiveness?

- Memantine Combined With Cholinesterase Inhibitors

- How Does Memantine Compare to Other Dementia Medications?

- What Are the Limitations of Memantine Treatment?

- New 2025 Data on Memantine and Mortality

- What to Expect Going Forward in Dementia Pharmacology

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Does Memantine Work in Moderate to Severe Dementia?

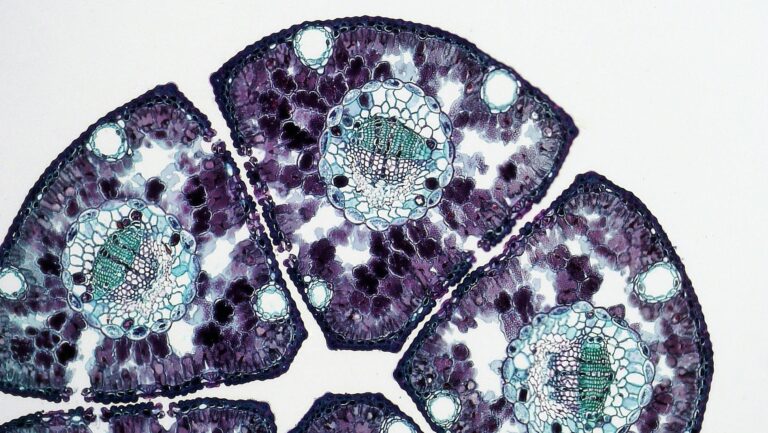

Memantine occupies a unique position in Alzheimer’s pharmacology because it works through an entirely different mechanism than the other approved drugs. Most dementia medications — donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine — are cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs), which work by preventing the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter critical to memory and learning. Memantine does not touch the cholinergic system. Instead, it is an NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist, which means it blocks a specific type of receptor involved in learning and memory that becomes pathologically overactivated in Alzheimer’s disease. In a damaged Alzheimer’s brain, glutamate is chronically released at low levels, keeping NMDA receptors in a state of continuous, low-grade activation. This persistent activation is toxic to neurons — a process called excitotoxicity — and is thought to contribute to the progressive neuronal death seen in the disease. Memantine works by partially blocking these receptors in a way that reduces the background noise of glutamate overactivation without eliminating the sharp, high-level receptor activation that is essential for genuine learning signals.

Think of it as reducing a constant background hum that is drowning out actual signal. By doing so, memantine protects neurons from excitotoxic damage and may allow remaining circuits to function more clearly. This mechanism also explains why memantine’s benefits are more pronounced in moderate-to-severe disease than in mild disease. At the moderate and severe stages, excitotoxicity has had more time to accumulate, and the glutamatergic system is more dysregulated. The drug finds more to correct. In mild Alzheimer’s, cholinergic deficits are the dominant feature, and ChEIs are the appropriate first-line treatment. The FDA has not approved memantine for mild Alzheimer’s, and clinical trial data does not support its use at that stage.

What Do Clinical Trials Show About Memantine’s Effectiveness?

The foundational evidence for memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s comes from a landmark trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2003. Patients with moderate-to-severe AD were randomized to receive memantine or placebo for 28 weeks. Those on memantine showed statistically significant benefits compared to placebo across multiple outcome measures, including cognitive performance and daily functioning. This was the trial that supported FDA approval and established memantine as a standard of care for later-stage Alzheimer’s. The Cochrane review, which aggregated data from approximately 14 high-quality randomized trials involving around 3,700 participants, confirmed and extended these findings. The evidence quality was rated as high-certainty for the main efficacy domains — cognition, activities of daily living, behavior, and global clinical impression. Crucially, benefits were observed across all four of these domains, not just in narrow cognitive testing.

For dementia caregivers, the behavioral and daily functioning outcomes often matter most: a patient who is less agitated and better able to participate in basic self-care is a substantially different caregiving experience than one who is not. However, a critical limitation must be stated plainly: the benefits, while statistically significant, are described in the literature as “small.” Memantine does not restore lost function. It does not return a person with moderate Alzheimer’s to mild or early-stage function. The measured improvements are real and consistent across studies, but they are incremental. Families and clinicians should enter treatment with calibrated expectations — the goal is slowing decline, not reversing it. For some patients and families, even a modest delay in functional deterioration is highly meaningful. For others, the benefit may not justify the cost and logistics of another medication, particularly in patients with complex polypharmacy.

Memantine Combined With Cholinesterase Inhibitors

One of the more clinically significant questions is whether memantine adds benefit when a patient is already taking a cholinesterase inhibitor — a common scenario since many patients are placed on donepezil or a similar drug at the mild stage and continue it as disease progresses. The 2012 DOMINO trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, directly addressed this question. It found that continuing donepezil and adding memantine produced less deterioration than placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe AD. The combination outperformed either drug discontinued or replaced. This finding matters because it gives clinicians a rational basis for combination therapy at the moderate-to-severe stage.

Rather than stopping the cholinesterase inhibitor when the disease advances — a decision sometimes made on the assumption that the drug is no longer doing meaningful work — the DOMINO trial suggests continuing it alongside memantine may provide additive benefit. The two drugs work through entirely different mechanisms (cholinergic versus glutamatergic pathways), which supports the rationale for combining them without pharmacological redundancy. A practical example: a patient who has been on donepezil since a mild Alzheimer’s diagnosis three years ago reaches the moderate stage. Rather than discontinuing donepezil and switching to memantine, the DOMINO evidence supports adding memantine while continuing donepezil. The combined approach showed less functional decline over the trial period than continuing donepezil alone or adding memantine while discontinuing donepezil. Clinicians and caregivers should discuss this option explicitly at the transition point between mild and moderate disease, as this decision window is often missed in busy clinical practice.

How Does Memantine Compare to Other Dementia Medications?

At the moderate-to-severe stage, memantine and the cholinesterase inhibitors are the main pharmacological options, and understanding how they differ is essential for informed decision-making. Cholinesterase inhibitors — donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine — work primarily by boosting acetylcholine activity and are approved across mild, moderate, and in some formulations, severe Alzheimer’s. Memantine is specifically approved for moderate-to-severe disease and represents a completely different pathway. They are not substitutes for each other at this stage; they are potentially complementary. In terms of side effect profiles, the drugs differ meaningfully. Cholinesterase inhibitors are associated with gastrointestinal side effects — nausea, vomiting, diarrhea — particularly at initiation or dose increases, and with bradycardia in patients with cardiac conditions.

Memantine’s side effect profile is generally milder. The Cochrane review found that dizziness occurred in 6.1% of memantine patients versus 3.9% on placebo — a roughly 1.6-fold increase that is clinically manageable. Importantly, the Cochrane data showed no significant difference in falls between memantine and placebo, which is a notable finding given the high fall risk in this patient population and the legitimate concern about dizziness causing falls. The tradeoff between these drug classes is not purely clinical — it also involves cost and availability. Generic memantine is widely available and generally affordable. For patients who cannot tolerate the GI side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine may represent a better-tolerated alternative at the moderate-to-severe stage, rather than simply an add-on. This is worth discussing with a prescribing physician, particularly for patients with GI conditions or those who have already discontinued a ChEI due to side effects.

What Are the Limitations of Memantine Treatment?

The most important limitation of memantine is that it is a symptomatic treatment, not a disease-modifying one. It does not slow the underlying pathological process of Alzheimer’s — the accumulation of amyloid plaques and tau tangles, the neuroinflammation, the progressive neuronal death. What it does is modulate neuronal activity in a way that temporarily reduces the functional impact of that damage. When the drug is stopped, the benefit disappears. There is no lasting structural protection. This stands in contrast to the disease-modifying drugs that have entered the landscape more recently — lecanemab and donanemab, for example — which target amyloid and have shown actual slowing of disease progression in early-stage patients.

However, those drugs are approved for early-stage Alzheimer’s, are administered intravenously, require extensive monitoring for brain edema and microbleeds, and are far more expensive. They are not replacements for memantine at the moderate-to-severe stage; they represent a different intervention at a different point in the disease course. Memantine remains the pharmacological standard for the later stages where disease-modifying options do not yet exist. A second limitation is the absence of meaningful evidence in dementia types other than Alzheimer’s. Memantine is sometimes used off-label for vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia, but the evidence base for these conditions is substantially weaker than for Alzheimer’s. Clinicians prescribing memantine off-label for non-Alzheimer’s dementia should be transparent with families that the evidence is far less certain than it is for the Alzheimer’s indication.

New 2025 Data on Memantine and Mortality

A 2025 meta-analysis published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research added a potentially significant new dimension to the memantine picture. The analysis, which pooled data from 12 randomized controlled trials involving 4,266 patients and 7 observational studies involving over 20,000 patients, found that memantine use was associated with reduced all-cause mortality in patients with major cognitive disorders. This finding was not anticipated by the original clinical development program, which was focused on cognition and function.

The mortality finding should be interpreted cautiously — observational studies are subject to confounding, and the mechanism by which memantine might reduce mortality is not established. However, the breadth of the dataset (more than 24,000 patients across both study types) makes this signal worth noting. One plausible hypothesis is that by reducing neuronal excitotoxicity, memantine may provide a degree of neuroprotection that extends beyond measurable cognitive or functional metrics. For caregivers and clinicians already weighing whether to continue or initiate memantine in a frail patient with moderate-to-severe dementia, this mortality data may be relevant to the discussion even while awaiting further confirmation.

What to Expect Going Forward in Dementia Pharmacology

The treatment landscape for moderate-to-severe dementia is not static. Research into combination therapies, newer NMDA-targeting agents, and ultimately disease-modifying approaches for later stages of Alzheimer’s continues. In the near term, memantine remains the only FDA-approved option specifically indicated for the moderate-to-severe stage that addresses the glutamatergic system, and its position in standard care is unlikely to change without substantially stronger alternatives entering that indication. For families navigating these decisions now, the practical reality is that memantine is a well-studied, generally safe, and modestly effective tool.

It will not stop Alzheimer’s disease. It may help slow its functional progression, ease some behavioral symptoms, and — if the 2025 data holds up — may even reduce mortality risk. That is a meaningful constellation of benefits for a condition that currently offers no cures. Ongoing research will clarify which patients benefit most, how long treatment should continue, and whether the mortality benefit is real and mechanistically explainable.

Conclusion

Memantine is a legitimate, evidence-backed treatment for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease, with consistent benefits demonstrated across cognition, daily functioning, behavior, and global clinical status. Its FDA approval in 2003 marked the first time any drug had been specifically approved for the later stages of Alzheimer’s, and two decades of additional research have not undermined that approval — they have reinforced it. The benefits are real but modest. This is not a drug that reverses the disease or restores lost memory.

It is a drug that, for many patients, slows the rate of functional decline and may improve quality of life for both patient and caregiver. The decision to start or continue memantine should be made in consultation with a neurologist, geriatrician, or other physician experienced in dementia care. Patients already on a cholinesterase inhibitor who reach the moderate stage should specifically ask whether combination therapy is appropriate for their situation. The 2025 mortality data adds a new dimension to that conversation, even if it requires further confirmation. In a disease where therapeutic options remain limited and the stakes are high, memantine represents one of the more reliable tools currently available.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is memantine approved for mild Alzheimer’s disease?

No. Memantine is FDA-approved only for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. For mild Alzheimer’s, cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, rivastigmine, or galantamine are the standard pharmacological treatment. Clinical trial data has not demonstrated meaningful benefit from memantine at the mild stage.

Can memantine be taken along with donepezil or other cholinesterase inhibitors?

Yes, and the evidence supports doing so. The 2012 DOMINO trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that patients with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s who continued donepezil and added memantine showed less deterioration than those on placebo. The two drugs work through different mechanisms and are considered complementary rather than redundant.

What are the most common side effects of memantine?

Memantine is generally well-tolerated. The most commonly noted side effect is dizziness, which occurred in 6.1% of memantine-treated patients versus 3.9% on placebo in the Cochrane review data. Importantly, high-certainty evidence shows no significant increase in falls compared to placebo, which is reassuring given the dizziness risk.

Does memantine work for non-Alzheimer’s types of dementia?

Memantine is sometimes used off-label for vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia, but the evidence base for these conditions is far weaker than for Alzheimer’s disease. Families should have a direct conversation with the prescribing physician about the uncertainty involved in off-label use.

Does memantine slow the progression of Alzheimer’s or just manage symptoms?

Memantine is a symptomatic treatment, not a disease-modifying one. It does not slow the underlying pathological process of amyloid plaque formation or neuronal degeneration. It modulates glutamate activity in a way that may preserve function longer, but the benefits are symptomatic and do not persist after the medication is discontinued.

Is there any new research on memantine’s benefits beyond cognition and function?

Yes. A 2025 meta-analysis pooling data from 12 randomized trials and 7 observational studies — totaling more than 24,000 patients — found memantine associated with reduced all-cause mortality in patients with major cognitive disorders. This finding is promising but should be interpreted with caution pending further research to confirm the signal and clarify the mechanism.