On March 22, 1996, NASA astronaut Rich Clifford floated outside Space Shuttle Atlantis while docked to the Russian space station Mir, performing a six-hour spacewalk that would make history. What mission controllers and most of his colleagues did not know was that Clifford had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease two years earlier, at age 42. His right hand trembled as he struggled to get it into his spacesuit glove, but he completed the extravehicular activity anyway””becoming part of the first U.S. crew to conduct a spacewalk outside a shuttle docked with a space station.

His story illustrates both the profound ways Parkinson’s disease alters how a person moves through physical space and the remarkable human capacity to adapt. Parkinson’s disease fundamentally disrupts spatial navigation by depleting dopamine in the brain, which affects a person’s ability to control body movements, navigate around obstacles, and process their position relative to surrounding objects. For most people with Parkinson’s, this manifests as bumping into doorways, difficulty moving through crowds, and problems with three-dimensional spatial perception. For Clifford, it meant navigating the most extreme environment humans have ever entered while managing symptoms that would eventually end his flying career. This article explores how Parkinson’s disease affects the brain’s spatial processing systems, examines Clifford’s remarkable achievement in detail, discusses emerging research connecting space travel itself to Parkinson’s-like symptoms, and offers perspective on what his story means for the broader Parkinson’s community.

Table of Contents

- How Did an Astronaut with Parkinson’s Complete a Spacewalk?

- What Happens to Spatial Awareness When Dopamine Disappears?

- The Hidden Challenge of Moving Through Everyday Environments

- What Space Travel Research Reveals About Parkinson’s Mechanisms

- Why Clifford Kept His Diagnosis Secret””and What Changed

- Living with Spatial Challenges on Earth

- What Clifford’s Legacy Means for Parkinson’s Awareness

- Conclusion

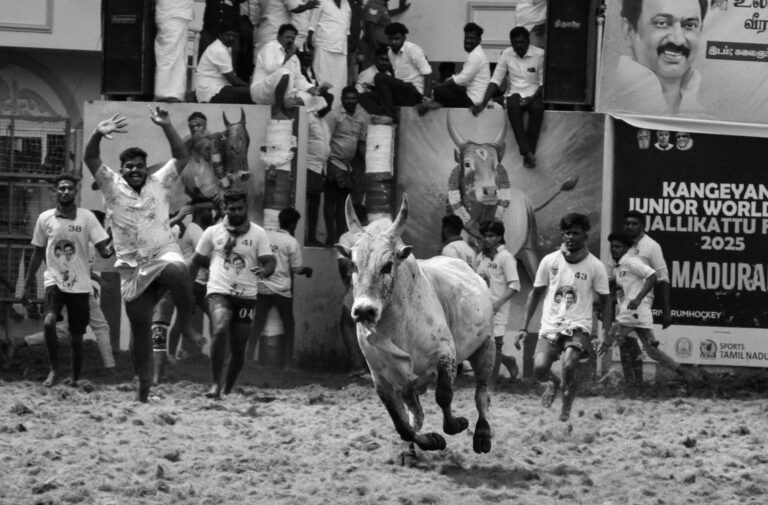

How Did an Astronaut with Parkinson’s Complete a Spacewalk?

Rich Clifford’s diagnosis came after his second space shuttle mission in 1994, when doctors noticed his right arm wasn’t swinging naturally as he walked. The symptoms were initially mild””subtle enough that Clifford could pass the rigorous medical evaluations required for spaceflight. NASA kept his condition confidential, and Clifford continued training for what would become his most challenging mission. The STS-76 mission required Clifford to perform complex tasks in a bulky spacesuit while floating in the vacuum of space. During the six-hour, two-minute, and twenty-eight-second spacewalk with astronaut Linda Godwin, Clifford later recalled that his hand was shaking as he tried to fit it into his glove.

The confined environment of a spacesuit, which requires precise fine motor control, presents challenges even for healthy astronauts. For someone with early-stage Parkinson’s affecting hand coordination, the difficulty was compounded significantly. What made his success possible was the combination of early-stage disease, extensive training, and the particular nature of spatial tasks in microgravity. In zero gravity, many of the balance and gait problems that plague Parkinson’s patients on Earth become less relevant. However, the mission also demonstrated Clifford’s own uncertainty about his future capabilities””after returning from Mir, he voluntarily stopped flying because he could not predict how quickly his symptoms might progress.

What Happens to Spatial Awareness When Dopamine Disappears?

The brain processes spatial information through two distinct systems. Egocentric processing helps you understand where objects are in relation to your own body””essential for reaching for a doorknob or stepping around furniture. Allocentric processing creates a mental map of the world independent of your position””like remembering that the bathroom is down the hall and to the left. Research has shown that Parkinson’s disease primarily impairs egocentric processing due to deterioration of the striatal and motor systems, while leaving allocentric navigation relatively intact. This distinction explains why many Parkinson’s patients report specific problems like bumping into doorframes or misjudging distances when reaching for objects, while still being able to navigate familiar routes from memory.

Studies examining three-dimensional spatial tasks have found that Parkinson’s patients make significantly more errors than healthy controls, suggesting particular problems with perceiving extra-personal space””the area beyond arm’s reach. However, these impairments vary considerably between individuals and across disease stages. Someone with early Parkinson’s, like Clifford in 1996, might experience only subtle difficulties that can be compensated for through concentration and practice. As the disease progresses, spatial navigation problems typically worsen, though the rate of decline is unpredictable. This uncertainty was precisely why Clifford chose to stop flying””not because he had failed, but because he could not guarantee future performance.

The Hidden Challenge of Moving Through Everyday Environments

For most people with Parkinson’s, spatial navigation challenges don’t occur in space but in the far more mundane environment of daily life. Walking through a crowded grocery store, navigating around furniture at home, or stepping through a narrow doorway can become surprisingly difficult. The absence of dopamine affects not only the planning of movements but also the real-time adjustments needed to avoid obstacles. Consider the simple act of walking through a doorway. A healthy brain automatically calculates the door’s width, the body’s position, and the required trajectory””all without conscious thought.

In Parkinson’s disease, this automatic processing becomes impaired. Patients often describe feeling as if their body doesn’t respond correctly to what their eyes are telling them, resulting in unexpected contact with doorframes or walls. Some research suggests this reflects a broader problem with integrating visual information and motor planning. A specific example from clinical observations: patients frequently report that narrow spaces feel threatening or difficult to navigate, even when intellectually they know they can fit through. This phenomenon relates to how Parkinson’s affects the perception of extra-personal space””the brain’s calculations about the spatial relationship between the body and surrounding objects become unreliable.

What Space Travel Research Reveals About Parkinson’s Mechanisms

An unexpected connection has emerged between space exploration and Parkinson’s disease research. Scientists studying the effects of spaceflight on the human body have observed molecular changes that mirror those seen in Parkinson’s: systemic mitochondrial dysfunction, alterations in dopamine systems, and changes in gait patterns. Space-flown animals and returning astronauts sometimes exhibit these Parkinson’s-like characteristics, prompting new research into the mechanisms underlying both conditions. This connection becomes particularly concerning when considering deep space missions. For journeys beyond low Earth orbit””such as a round trip to Mars lasting approximately 500 days””astronauts would be exposed to dramatically higher levels of cosmic radiation.

Researchers have raised concerns that this radiation exposure could elevate the risk of neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinsonism. The protective magnetic field that shields Earth-orbiting spacecraft does not extend into deep space. The tradeoff here is significant: while space exploration offers unprecedented opportunities for scientific discovery and human achievement, it may carry neurological risks we are only beginning to understand. This does not mean Mars missions should be abandoned, but it does suggest that radiation shielding and neuroprotective strategies should be research priorities. The parallel discoveries about dopamine dysfunction in both spaceflight and Parkinson’s may ultimately benefit both astronauts and the millions of people living with the disease on Earth.

Why Clifford Kept His Diagnosis Secret””and What Changed

Rich Clifford did not publicly disclose his Parkinson’s diagnosis until years after leaving NASA. The decision to keep his condition confidential during his final mission reflected both personal and professional calculations. NASA’s medical standards for astronauts are stringent, and uncertainty about how the agency would respond to a progressive neurological diagnosis likely influenced his choice. His eventual public advocacy marked a significant shift. Clifford became a spokesperson for Parkinson’s awareness, sharing his story through organizations like the Michael J.

Fox Foundation and the Parkinson’s Foundation. A 2014 documentary short titled “An Astronaut’s Secret” chronicled his experience of flying with the disease. By speaking openly, Clifford helped challenge assumptions about what people with Parkinson’s can accomplish while also being honest about the limitations the disease eventually imposed. The warning embedded in his story is important: early-stage Parkinson’s can be compatible with extraordinary achievement, but the disease is progressive and unpredictable. Clifford’s decision to stop flying voluntarily””rather than waiting for an incident or a failed medical evaluation””reflected mature judgment about risk management. His example suggests that people with Parkinson’s can accomplish remarkable things while also needing to make difficult decisions about when to step back from certain activities.

Living with Spatial Challenges on Earth

For the approximately one million Americans living with Parkinson’s disease, spatial navigation problems are a daily reality rather than an extraordinary circumstance. Occupational therapists and physical therapists have developed various strategies to help patients manage these challenges, from environmental modifications like removing clutter and improving lighting to cognitive techniques for consciously planning movements that were once automatic.

One practical example involves using visual cues to improve walking. Some patients find that placing tape strips on the floor creates targets to step over, which paradoxically helps them walk more smoothly than an unmarked floor. This works because the deliberate act of stepping over a line engages different neural pathways than automatic walking, temporarily bypassing some of the damaged systems.

What Clifford’s Legacy Means for Parkinson’s Awareness

Rich Clifford died on December 28, 2021, at age 69, having lived with Parkinson’s disease for 27 years following his diagnosis. His legacy extends beyond his NASA achievements to his role in demonstrating that a Parkinson’s diagnosis is not an immediate endpoint but the beginning of a different kind of journey. He navigated space””both orbital and personal””with a combination of skill, courage, and honest acknowledgment of his limitations.

His story offers perspective for everyone affected by Parkinson’s disease. The same brain changes that made it difficult for Clifford to get his hand into a spacesuit glove affect millions of people trying to button shirts, pour coffee, or walk through their own homes. Understanding these challenges scientifically, while also seeing what remains possible, provides a more complete picture of life with this condition than either despair or false optimism alone.

Conclusion

Rich Clifford’s experience demonstrates that Parkinson’s disease fundamentally alters spatial navigation by impairing the brain’s ability to process body position relative to surrounding objects””a challenge that manifested for him as a trembling hand inside a spacesuit glove during a historic spacewalk. His achievement aboard the Mir space station proved that early-stage Parkinson’s need not be immediately disabling, while his subsequent decision to stop flying illustrated the honest self-assessment the disease eventually requires. For those living with Parkinson’s or caring for someone who is, Clifford’s story provides both inspiration and realism.

The spatial awareness problems caused by dopamine depletion are real and progressive, affecting everything from walking through doorways to navigating crowded spaces. But understanding these mechanisms””and learning compensation strategies””can help maintain function and quality of life. Ongoing research connecting spaceflight physiology to Parkinson’s mechanisms may eventually benefit both astronauts and earthbound patients, turning an unexpected parallel into therapeutic progress.