COVID-19 does not simply pass through the brain and leave it unchanged. A growing body of research now confirms that SARS-CoV-2 infection accelerates cognitive decline in people who already have dementia and significantly raises the risk of new-onset dementia in previously healthy adults. A November 2024 meta-analysis published in The Lancet, drawing on 939,824 COVID survivors and 6.77 million controls, found a 58% higher risk of new-onset dementia among those who had been infected. For families already managing a loved one’s Alzheimer’s or vascular dementia diagnosis, the implications are serious and immediate — one study found that dementia patients who contracted COVID experienced cognitive decline at roughly 3.5 times the rate of those who did not.

This is not a fringe concern or a preliminary signal buried in a single dataset. The 2024 Lancet Standing Commission on Dementia added COVID-19-related factors to its updated list of modifiable dementia risk factors, and the European Academy of Neurology has called for long-term surveillance of post-COVID neurodegenerative disorders. The connection between the virus and the brain is being taken seriously at the highest levels of medical research. This article covers what the latest studies tell us about new-onset dementia risk, how COVID accelerates decline in those already diagnosed, what is happening at the biomarker level, and what families and clinicians can realistically do with this information right now.

Table of Contents

- How Does COVID-19 Accelerate Dementia Decline in People Already Diagnosed?

- New-Onset Dementia Risk After COVID-19 — Who Is Most Vulnerable?

- What COVID-19 Does to Alzheimer’s Biomarkers in the Brain

- Practical Steps for Families Managing Dementia During and After COVID

- The Biological Mechanisms Behind COVID’s Brain Damage

- Cognitive Damage in Previously Healthy Adults After COVID

- Where Research Goes From Here

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Does COVID-19 Accelerate Dementia Decline in People Already Diagnosed?

For someone living with dementia, COVID-19 appears to act like a chemical accelerant on an already burning fire. A 2023 study published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine tracked dementia patients who had contracted COVID against those who had not and found that cognitive decline was approximately 3.5 times more frequent in the infected group. The numbers on standardized testing were stark: MMSE scores dropped at a rate of 3.3 points per year in COVID-infected dementia patients, compared to 1.7 points per year in those who avoided the virus. To put that in practical terms, the difference between a 1.7-point and a 3.3-point annual decline can mean the difference between a person who still recognizes family members and participates in daily routines versus one who cannot. The consequences extend well beyond test scores. That same study found that 45% of dementia patients who had COVID required new institutionalization — meaning they could no longer be cared for at home — compared to 20% of those who did not contract the virus.

For families, this is where the data stops being abstract. A loved one who might have remained at home for another year or two with support may instead need full-time residential care months earlier than anticipated. The financial and emotional weight of that acceleration is enormous. Even the pandemic lockdowns themselves, separate from direct infection, appeared to worsen outcomes. A 2021 study found that monthly cognitive score decline in dementia patients went from 0.2 points before lockdown to 0.53 points during lockdown — a statistically significant jump. Social isolation, disrupted routines, reduced physical activity, and loss of in-person therapeutic contact all likely contributed. This means dementia patients were hit from two directions: the virus itself and the public health measures necessary to contain it.

New-Onset Dementia Risk After COVID-19 — Who Is Most Vulnerable?

The risk is not limited to people who already had cognitive problems. Among previously healthy individuals, COVID-19 appears to trigger new dementia diagnoses at rates that have caught researchers’ attention. The Lancet meta-analysis found new-onset dementia incidence of 1.82% in the COVID group versus 0.35% in controls over a median 12-month follow-up. While 1.82% may sound small in isolation, it represents a fivefold increase in absolute incidence and, across hundreds of millions of global infections, translates to an enormous number of new cases. A critical detail that often gets lost in headlines: the increased dementia risk appears to be primarily driven by vascular dementia rather than Alzheimer’s disease, according to a 2025 analysis published in npj Dementia.

This distinction matters because vascular dementia results from impaired blood flow to the brain, and COVID-19 is well established as a disease that damages blood vessels throughout the body. However, this does not mean Alzheimer’s patients are unaffected — the biomarker data, which we will examine shortly, suggests otherwise. The vascular dementia finding does mean that people with pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors — hypertension, diabetes, obesity — may face a compounded threat when they contract COVID. Among post-acute COVID patients aged 65 and older, new-onset cognitive impairment accounted for more than 50% of cases in one 2024 analysis. A global study of over 3,500 adults from eight countries, published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience in January 2025 by researchers at UT Health San Antonio, found noticeable declines in memory, language, and executive functioning after long COVID, especially in those who lost their sense of smell. If your parent or grandparent had COVID and you have noticed they seem foggier, slower to find words, or less organized in their thinking, you are not imagining things — and you are not alone.

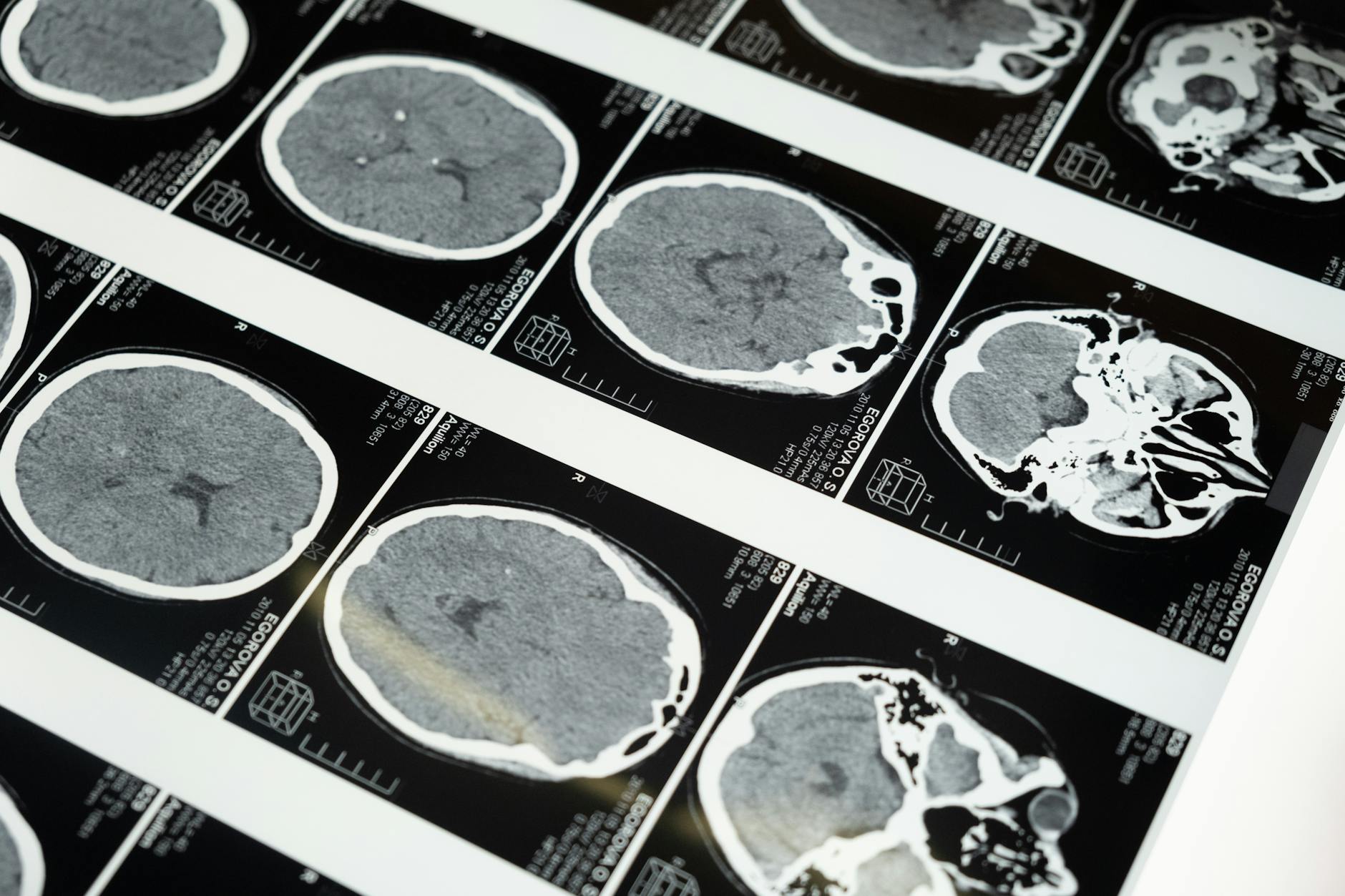

What COVID-19 Does to Alzheimer’s Biomarkers in the Brain

Some of the most unsettling evidence comes not from cognitive tests but from direct biological measurements. A 2024 study published in Nature Medicine examined plasma biomarkers in 75-year-old COVID survivors compared to matched controls and found an 8.2% extra increase in p-tau-181, a 4.7% decrease in amyloid-beta 42, and a 2.3% decrease in the amyloid-beta 42-to-40 ratio. These are the hallmark indicators of Alzheimer’s disease pathology — rising tau and falling amyloid-beta in cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma are the biochemical signature of a brain accumulating the plaques and tangles that define Alzheimer’s. These biomarker changes were more severe in hospitalized COVID patients and in those with pre-existing hypertension, reinforcing the idea that vascular health and COVID severity interact to amplify brain damage. Postmortem brain samples told a similar story: a 2024 PMC study found abnormal hyperphosphorylated tau accumulation in the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex — two regions critical for memory — within just 4 to 13 months after COVID recovery, along with prolonged glial activation indicating ongoing brain inflammation.

What makes this particularly concerning is the timeline. These are not changes that took decades to develop, as Alzheimer’s pathology typically does. They appeared within months of infection. Whether they represent a temporary inflammatory response that might partially reverse or a permanent acceleration of neurodegenerative disease is one of the most important open questions in dementia research right now. Families should be aware that we do not yet know if these biomarker shifts inevitably lead to clinical dementia, but the direction of the evidence is worrying enough that researchers are treating it with urgency.

Practical Steps for Families Managing Dementia During and After COVID

Given what we now know, families caring for someone with dementia face a difficult set of tradeoffs. The most obvious step — preventing COVID infection in the first place — remains the single most impactful action. Staying current on vaccinations, improving indoor ventilation, and using high-quality masks in crowded settings are all evidence-based strategies. But these measures come with their own costs. Overly restrictive isolation can itself worsen cognitive decline, as the lockdown data showed. The challenge is finding the right balance between infection prevention and maintaining the social engagement, physical activity, and routine that dementia patients need. If a person with dementia does contract COVID, families should request a cognitive baseline assessment as soon as the acute illness resolves, and then follow-up testing at three, six, and twelve months.

The MMSE or MoCA are standard tools that any primary care physician can administer. Documenting any decline early allows for adjustments to care plans, medication management, and living arrangements before a crisis forces the issue. The data showing that 45% of COVID-infected dementia patients required new institutionalization suggests that early planning — including conversations about care facility options and financial resources — is not premature. It is practical. For previously healthy older adults who had COVID and are now experiencing persistent cognitive symptoms, a thorough evaluation is warranted. This should include not just cognitive testing but also cardiovascular assessment, given the vascular dementia link. Do not accept “long COVID brain fog” as a complete explanation without investigation. Brain fog is a symptom description, not a diagnosis, and some of the underlying causes — small vessel disease, treatable inflammation, medication interactions — may be addressable.

The Biological Mechanisms Behind COVID’s Brain Damage

Understanding why COVID affects the brain is not just an academic exercise — it shapes treatment strategies. Researchers have identified several mechanisms working in parallel. Neuroinflammation is perhaps the most well-documented: prolonged brain inflammation and microglial activation persist for months after the initial infection has cleared. Microglia are the brain’s immune cells, and when they remain in an activated state, they can damage the very neurons they are supposed to protect. This sustained inflammatory response is a plausible explanation for the accelerated tau accumulation seen in postmortem studies. Cerebrovascular damage is another major pathway.

COVID-19 causes endothelial dysfunction and microclotting throughout the body, and the brain’s dense network of tiny blood vessels is particularly vulnerable. This mechanism aligns with the finding that vascular dementia, rather than Alzheimer’s, is the primary driver of increased post-COVID dementia diagnoses. Direct viral neuroinvasion — meaning the virus literally infects brain tissue — has also been documented, and there is evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can alter amyloid processing once inside neural cells. A 2025 study published in PMC identified shared molecular pathways at the transcription level between COVID-19 and Alzheimer’s disease, suggesting that the overlap between these two conditions is not coincidental but rooted in common biological processes. However, a critical limitation of much of this research is that it remains observational. We can see that COVID and accelerated neurodegeneration co-occur and share biological features, but proving direct causation — and distinguishing it from confounding factors like hospitalization stress, medication effects, and pre-existing vulnerabilities — requires longer-term controlled studies that are still underway.

Cognitive Damage in Previously Healthy Adults After COVID

The assumption that post-COVID cognitive problems are limited to the elderly or those with pre-existing conditions is wrong. Among COVID-19 patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation, 80% had mild to severe cognitive impairments, with over half showing working memory deficits, according to NIH COVID-19 research. These were not all frail, elderly patients — rehabilitation populations include people recovering from severe illness across a range of ages.

The global study from UT Health San Antonio is particularly instructive because it was large, international, and identified a specific clinical marker — loss of smell — as a predictor of worse cognitive outcomes. Anosmia, or smell loss, indicates that the virus reached the olfactory bulb, which sits at the base of the brain and connects directly to memory-processing regions. If someone you know had COVID, lost their sense of smell for an extended period, and now seems cognitively different, that clinical history should be communicated to their physician. It is not a guarantee of future dementia, but it is a red flag worth monitoring.

Where Research Goes From Here

The scientific community is no longer debating whether COVID-19 affects the brain. The question has shifted to how much, for how long, and what can be done about it. The 2025 NIH Alzheimer’s Disease Research Progress Report acknowledges COVID-19 as a contributor to dementia research priorities, and the European Academy of Neurology’s position paper calling for long-term surveillance reflects a consensus that this problem will not resolve itself without sustained attention and funding.

The most important studies in the coming years will track COVID survivors over five- and ten-year windows to determine whether the biomarker changes and accelerated cognitive decline observed so far represent a temporary insult or the opening chapter of a long-term neurodegenerative process. For families, the practical takeaway is straightforward: treat COVID prevention in dementia patients as a clinical priority, not a personal preference, and do not dismiss new cognitive symptoms in anyone — regardless of age — who has had COVID. The data is strong enough to warrant vigilance, even as the full picture continues to develop.

Conclusion

The evidence linking COVID-19 to accelerated dementia decline and new-onset dementia is substantial and growing. A 58% increased risk of new-onset dementia in survivors, cognitive decline rates 3.5 times higher in infected dementia patients, biomarker shifts consistent with Alzheimer’s pathology appearing within months of infection, and nearly half of COVID-infected dementia patients requiring institutionalization — these are not marginal findings.

They represent a significant public health burden that will unfold over the coming decade as the long-term consequences of hundreds of millions of infections become clearer. For families, the path forward involves prevention where possible, early and repeated cognitive assessment after infection, honest conversations about care planning, and a refusal to dismiss new cognitive symptoms as normal aging or “just brain fog.” For the medical community, it means integrating COVID history into dementia risk assessments as routine practice and funding the longitudinal studies needed to answer the questions that remain. The virus may have left the headlines, but it has not left the brain, and acting on what we already know is the most responsible course available.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a single mild COVID infection cause dementia?

The current evidence does not show that a single mild infection reliably causes dementia in healthy individuals. The 58% increased risk identified in The Lancet meta-analysis reflects a population-level trend, not an individual certainty. However, even mild infections have been associated with measurable biomarker changes, so dismissing any infection as inconsequential is not supported by the data either.

Does vaccination protect against COVID-related cognitive decline?

Vaccination reduces the risk of severe COVID-19, and the biomarker studies show that hospitalized patients experience worse cognitive outcomes than those with milder illness. While no study has yet definitively proven that vaccination prevents post-COVID dementia specifically, reducing infection severity is a plausible and evidence-consistent protective strategy.

Is COVID-related dementia the same as Alzheimer’s disease?

Not necessarily. The increased dementia risk after COVID is primarily driven by vascular dementia, which results from blood vessel damage in the brain, rather than Alzheimer’s disease. However, COVID does appear to accelerate Alzheimer’s-type biomarker changes, including increased tau phosphorylation and decreased amyloid-beta levels, so the two conditions may overlap in some patients.

How soon after COVID infection can cognitive decline appear?

Postmortem studies have found abnormal tau accumulation in the brain as early as 4 months after COVID recovery. Clinically, cognitive changes have been documented within the first year post-infection, which is the follow-up window used in most current studies.

Should dementia patients avoid all social contact to prevent COVID?

No. The lockdown data showed that social isolation itself accelerates cognitive decline in dementia patients, with monthly score drops increasing from 0.2 to 0.53 points during lockdowns. The goal should be risk-balanced engagement — using ventilation, vaccination, and masks to reduce transmission risk while maintaining the social stimulation and physical activity that are protective for brain health.

What should I tell my parent’s doctor if they had COVID and seem worse cognitively?

Request a formal cognitive assessment using a standardized tool like the MMSE or MoCA, and ask for follow-up testing at regular intervals. Mention if they lost their sense of smell during COVID, as this has been linked to worse cognitive outcomes. Also request a cardiovascular evaluation, given the vascular dementia connection.