A neurologist cannot reliably diagnose dementia in a single visit in most cases. The short answer is that one appointment is rarely enough — and expecting a confirmed diagnosis after a first consultation often leads to frustration or, worse, premature conclusions. According to the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, most patients require two to three visits before a cause can be identified and treatment discussed. That said, in straightforward cases where symptoms are clear and certain results can be reviewed same-day, a neurologist may form a strong clinical impression at the first visit — but even then, a definitive diagnosis almost always waits for imaging and lab results to return. Consider someone in their late seventies whose family has noticed significant memory lapses over the past year — forgetting conversations entirely, getting lost on familiar routes, struggling to manage bills.

At a first visit, a neurologist will take a full history, run cognitive screening tests, order blood work, and refer for brain imaging. But the MRI results won’t be ready that afternoon. The blood panel won’t come back before the patient leaves. A follow-up visit is all but certain. This article covers what actually happens during a dementia evaluation, why the process unfolds across multiple appointments, what tests are involved, and what families should expect when seeking a diagnosis.

Table of Contents

- What Does a Neurologist Actually Do in the First Dementia Visit?

- Why Imaging Results Make a Single-Visit Diagnosis Nearly Impossible

- The Role of Neuropsychological Testing in Dementia Diagnosis

- Who Is Most Likely to Need Multiple Specialist Visits?

- Blood Biomarker Tests and the Evolving Speed of Diagnosis

- What Families Should Know Before the First Appointment

- Where Dementia Diagnosis Is Headed

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Does a Neurologist Actually Do in the First Dementia Visit?

The first appointment with a neurologist for a suspected dementia evaluation is more thorough than many patients anticipate. It typically begins with a comprehensive medical and psychiatric history — including any family history of dementia or neurological disease — followed by a physical neurological exam assessing reflexes, coordination, balance, and sensory responses. The neurologist is looking for physical signs that might point toward specific conditions, whether that’s Parkinson’s disease, vascular dementia, or something else entirely. Cognitive testing happens during this visit as well. The most commonly used tools include the Mini-Mental State Examination and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment, a twelve-question screening that tests memory, orientation, attention, language, and executive function. These are brief screening instruments — not definitive diagnostic tools.

A person might score below normal on one and still have a treatable condition unrelated to dementia, such as hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, or severe depression. That’s precisely why blood tests are ordered at this stage: to rule out reversible causes before a dementia label is applied. The distinction matters. Cognitive screening results are a starting point, not an endpoint. A patient who scores poorly on a Montreal Cognitive Assessment on a day when they haven’t slept well or are anxious may look very different on a re-test. Neurologists trained in memory disorders know this, which is why the first visit is best understood as the beginning of an evaluation rather than its conclusion.

Why Imaging Results Make a Single-Visit Diagnosis Nearly Impossible

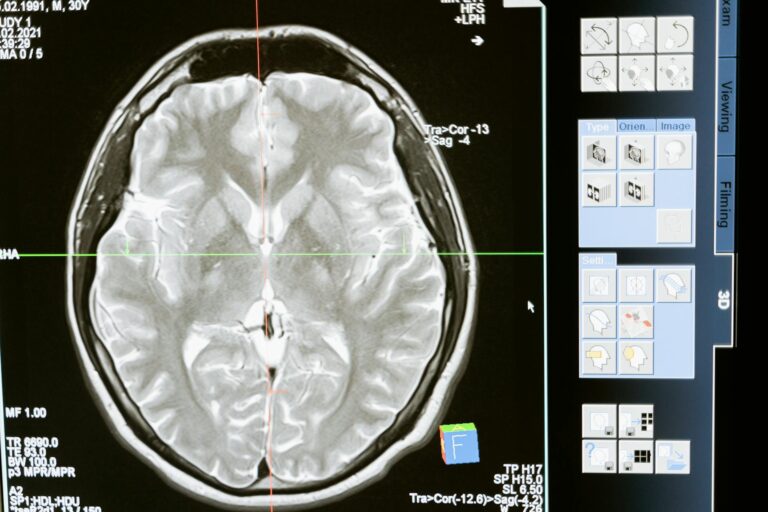

One of the most consistent obstacles to same-day dementia diagnosis is imaging. According to the Mayo Clinic and Stanford Health Care, brain imaging — whether MRI, CT, or PET scan — is typically ordered at the first appointment, but results are not available before the patient leaves. MRI scans in particular require radiologist review and often take days to return a formal report. PET scans, which can detect amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease, involve even more complex scheduling and interpretation. This creates a structural gap in the single-visit model.

Even if a neurologist develops a strong clinical suspicion during the first appointment — noting significant cognitive impairment on screening tests, a family history consistent with Alzheimer’s, and reported functional decline — they cannot confirm that suspicion without knowing what the brain scan shows. Imaging can reveal white matter changes consistent with vascular dementia, identify atrophy patterns that suggest frontotemporal dementia, or rule out other causes like a brain tumor or normal pressure hydrocephalus entirely. However, there is an important exception: in cases where prior imaging has already been done and is available for the neurologist to review at the first visit, the timeline can compress significantly. A patient who arrives with a recent MRI already on file gives the neurologist a considerable head start. Even so, that scenario is relatively rare for patients presenting for a first formal dementia evaluation.

The Role of Neuropsychological Testing in Dementia Diagnosis

For many patients — particularly younger ones or those with atypical or ambiguous presentations — neuropsychological testing is a critical component of the diagnostic process. This is a separate appointment from the initial neurologist visit and is conducted by a neuropsychologist rather than a neurologist. According to research published in PMC/NIH, neuropsychological assessment is considered the gold standard for distinguishing between types of dementia and for identifying subtle cognitive impairment that screening tools can miss. The testing itself is extensive.

A full neuropsychological battery can take six to eight hours, spread across one or two sessions. It evaluates memory, language, attention, processing speed, visuospatial skills, and executive function through a detailed series of standardized tasks. The results are then interpreted alongside the neurologist’s findings and imaging results to build a complete picture of the patient’s cognitive profile. For a sixty-two-year-old presenting with word-finding difficulties and behavioral changes — symptoms that could suggest early Alzheimer’s, frontotemporal dementia, or a psychiatric condition — neuropsychological testing is often the piece that tips the diagnostic balance. Without it, a neurologist may have a working hypothesis but not enough information to commit to a specific dementia type, which matters enormously for treatment planning and family counseling.

Who Is Most Likely to Need Multiple Specialist Visits?

The complexity of a dementia evaluation scales with the complexity of the patient. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, people under age sixty-five or those with atypical symptoms are especially likely to require evaluation by two or more specialists whose findings must be combined before a diagnosis is reached. This might include a neurologist, a neuropsychologist, a geriatric psychiatrist, and occasionally a geneticist if hereditary dementia is suspected. Younger patients present a particular diagnostic challenge. Early-onset dementia — defined as dementia appearing before age sixty-five — is statistically less common, and its presentation often looks different from late-onset Alzheimer’s.

Symptoms may be predominantly behavioral (as in frontotemporal dementia), predominantly visual (as in posterior cortical atrophy), or predominantly motor-related. A single neurologist reviewing the case without input from a specialist in behavioral neurology or movement disorders may not have the full picture. The tradeoff here is significant. Pursuing multiple specialists takes time — sometimes months, particularly in regions with long wait lists for neurology appointments. But rushing toward a single-visit conclusion in a complex case can result in a wrong diagnosis, which carries its own costs: inappropriate medications, missed treatable causes, and family members making care decisions based on inaccurate information.

Blood Biomarker Tests and the Evolving Speed of Diagnosis

In 2024 and 2025, blood-based biomarker testing has emerged as a meaningful development in dementia diagnosis. Tests measuring plasma amyloid and phosphorylated tau levels can now detect Alzheimer’s-related changes in the blood, offering a less invasive and less expensive alternative to PET scans or lumbar punctures. According to the National Institute on Aging, these tests are increasingly being incorporated into dementia evaluations and may help accelerate the diagnostic timeline. The important caveat is that blood biomarker tests still require laboratory turnaround time. Results are not available during the appointment at which the blood is drawn, which means they don’t collapse the process into a single visit.

They do, however, compress the number of visits needed in some cases and may reduce the need for more invasive procedures. A patient who might previously have needed a PET scan or cerebrospinal fluid analysis to confirm Alzheimer’s pathology may now get that information more quickly through a blood draw. The warning is this: blood biomarkers are not yet universal in clinical practice, and their interpretation requires expertise. A positive plasma amyloid result in a patient with mild cognitive impairment does not automatically mean that patient has Alzheimer’s dementia — context matters. Neurologists and primary care physicians unfamiliar with these tests risk either over-interpreting or under-utilizing them, which is why they are currently most reliable when used within a specialist memory clinic setting.

What Families Should Know Before the First Appointment

Preparation makes a measurable difference in the quality of a first dementia evaluation. Families who arrive with documented observations — a written timeline of symptom progression, a list of all current medications, prior medical records, and any existing cognitive test results — give the neurologist more material to work with from the outset. Some memory clinics send questionnaires in advance for family members to complete, precisely because collateral history is as diagnostically important as the patient’s own account.

It also helps to understand what the visit will not produce. Walking out of a first neurology appointment without a diagnosis is not a sign that something went wrong. It is the expected result of a process that requires time and multiple data points. Families who understand this in advance are better positioned to navigate the weeks between visits without misinterpreting the absence of an immediate answer as a medical failure.

Where Dementia Diagnosis Is Headed

The diagnostic process for dementia is changing, driven by advances in biomarker research, digital cognitive assessment tools, and telemedicine. Blood tests that can detect Alzheimer’s pathology years before symptoms fully emerge are moving from research settings into clinical use. Artificial intelligence tools that analyze MRI patterns or speech samples for early signs of neurodegeneration are in active development.

These technologies hold genuine promise for shortening the diagnostic timeline. Even so, the fundamental structure of dementia diagnosis — careful history-taking, clinical examination, cognitive testing, imaging, laboratory work, and specialist review — is unlikely to collapse into a single appointment in the near future. The complexity of the brain, the overlap between dementia types, and the need to rule out treatable mimics mean that a thorough evaluation will remain a multi-visit process for the foreseeable future. What may change is how much can be accomplished before the first appointment, and how quickly results return afterward.

Conclusion

A neurologist can begin a dementia evaluation in one visit, and in rare, clear-cut cases may form a strong clinical impression that amounts to a working diagnosis. But a confirmed diagnosis — the kind that accounts for imaging results, laboratory findings, and sometimes neuropsychological testing — almost always requires more than one appointment. The standard is two to three visits, and for younger patients or those with complex presentations, the process may involve multiple specialists over several months.

That timeline exists not because the medical system is slow, but because dementia diagnosis done correctly is genuinely difficult and the stakes of getting it wrong are high. For families in the middle of this process, the most useful frame is this: the first visit is not meant to end with an answer. It is meant to gather the information needed to find one. Understanding that distinction reduces anxiety, improves preparation for follow-up appointments, and helps families ask better questions at each stage of the evaluation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a primary care doctor diagnose dementia, or does it have to be a neurologist?

A primary care physician can make a dementia diagnosis in straightforward cases, particularly for older patients with typical Alzheimer’s presentations. However, complex or atypical cases — especially in patients under sixty-five — are generally referred to a neurologist or a specialist memory clinic for a more thorough evaluation.

How long does the full dementia diagnostic process typically take?

From the first appointment to a confirmed diagnosis, the process commonly takes several weeks to a few months. Wait times for neurology appointments, imaging scheduling, and laboratory turnaround all contribute to the timeline. In areas with limited specialist access, the wait can be longer.

What is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and what does it test?

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or MoCA, is a twelve-question screening tool used to detect mild cognitive impairment. It evaluates memory, orientation, attention, language, visuospatial skills, and executive function. A score below 26 out of 30 is generally considered below normal, but the test is a screening instrument, not a standalone diagnostic tool.

Is neuropsychological testing always required for a dementia diagnosis?

Not always. In older patients with clear-cut Alzheimer’s presentations, a diagnosis may be reached without a full neuropsychological battery. However, for younger patients, those with unusual symptom patterns, or cases where the dementia type is unclear, neuropsychological testing — which can take six to eight hours — is often essential for accurate diagnosis.

What are blood biomarker tests and are they widely available?

Blood biomarker tests measure proteins like amyloid and phosphorylated tau that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. As of 2024 and 2025, these tests are increasingly available and may help accelerate diagnosis. However, they still require lab turnaround time and are most reliably interpreted within specialist memory clinic settings rather than in general practice.

Should a family member come to the first neurology appointment?

Yes, whenever possible. A family member or close friend who has observed the patient’s symptoms over time provides collateral history that is often as diagnostically valuable as the patient’s own account. Patients with cognitive impairment may not accurately report the frequency or severity of their symptoms, making an outside observer’s perspective important.