For a person diagnosed with dementia at age 100, the average remaining lifespan is approximately 1.5 to 2.5 years. That number may sound stark, but it carries an important nuance that families often miss: at age 100, baseline life expectancy — with or without dementia — is itself only about 1.5 to 2.5 years. In other words, a dementia diagnosis at this extreme age does not dramatically shorten life the way it does for someone diagnosed at 65 or 75. Consider a centenarian named Margaret who receives an Alzheimer’s diagnosis on her 100th birthday. Her family might fear the worst, but the research suggests her remaining timeline may not look radically different from that of her cognitively intact peers in the same age bracket.

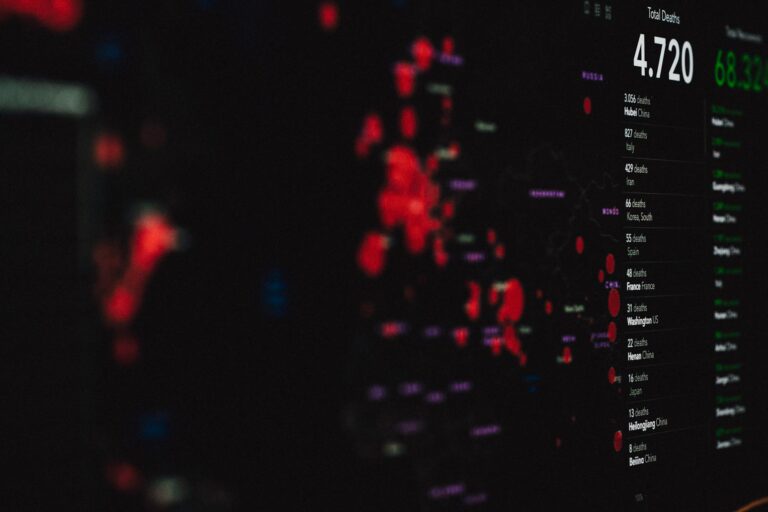

This article covers what the latest research tells us about survival after dementia diagnosis across age groups, why centenarians represent a unique case, what neuropathological findings reveal about the oldest brains, and how families can approach care planning when a loved one reaches this rare milestone. The data behind this estimate draws on decades of research, including a landmark 2024–2025 systematic review published through BMJ that analyzed 261 studies spanning 1984 to 2024 and involving over 5 million people with dementia. That review, along with findings from The 90+ Study and other centenarian-focused research, paints a picture of dementia at extreme old age that defies some common assumptions. Survival timelines shrink with age at diagnosis, but so does the gap between those with dementia and those without it. Understanding this relationship matters for families making difficult decisions about care, comfort, and quality of life.

Table of Contents

- How Long Does a Person Typically Survive After a Dementia Diagnosis at Age 100?

- Why Dementia at 100 Behaves Differently Than Dementia at 70

- What Happens Inside a Centenarian’s Brain

- How Families Should Approach Care Planning After a Diagnosis at 100

- The Limits of What Survival Statistics Can Tell Us

- When Dementia Appears Very Late, Duration Tends to Be Short

- What Centenarian Research May Reveal About the Future of Dementia

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Long Does a Person Typically Survive After a Dementia Diagnosis at Age 100?

No single study provides a precise survival figure for dementia diagnosed at exactly age 100, but researchers can triangulate from overlapping datasets. The BMJ-affiliated meta-analysis found that average survival after dementia diagnosis is strongly age-dependent, ranging from 8.9 years for women diagnosed around age 60 down to just 2.2 years for men diagnosed around age 85. For those diagnosed after age 90, a separate analysis reported in Euronews Health placed average survival at approximately 2.6 years. A BMJ cohort study broke it down further by decade: median survival was 10.7 years for ages 65 to 69, 5.4 years for ages 70 to 79, 4.3 years for ages 80 to 89, and 3.8 years for those 90 and older. Given this downward curve, extrapolating to age 100 yields an estimated survival of roughly 1.5 to 2.5 years. But individual variation is enormous.

Some centenarians with dementia live several more years; others decline rapidly within months. What makes the centenarian data unique is that the comparison group — 100-year-olds without dementia — is already living on borrowed time by any actuarial measure. When researchers from The 90+ Study examined individuals aged 90 and over, they found that dementia did not significantly increase the mortality rate compared to non-dementia individuals of the same age. That finding is striking. At younger ages, a dementia diagnosis roughly halves remaining life expectancy. At 100, the diagnosis is less a predictor of death than a companion to an already limited horizon.

Why Dementia at 100 Behaves Differently Than Dementia at 70

The conventional understanding of dementia as a life-shortening diagnosis holds true across most of the age spectrum, but it begins to break down at the extreme end. A 70-year-old diagnosed with Alzheimer’s might reasonably expect to live another 5.4 years on average, compared to a life expectancy of perhaps 14 to 16 more years without the diagnosis. That gap — roughly a decade — is devastating. At 100, however, the gap between dementia and non-dementia survival narrows to the point of near-insignificance. The reason is mathematical as much as biological: when baseline life expectancy is already measured in months rather than decades, there is simply less life for dementia to “take away.” However, this does not mean the experience of dementia at 100 is mild or inconsequential.

The disease still robs a person of memory, recognition, and independence. Families should not interpret the survival data as evidence that late-life dementia is somehow less serious. What it does mean, practically, is that the care focus should lean heavily toward comfort, dignity, and quality of remaining days rather than aggressive intervention. A warning worth noting: some families, upon hearing that survival is similar with or without dementia, assume a diagnosis is not worth pursuing at all. But a formal diagnosis still matters. It guides medication decisions, informs care planning, helps families access hospice and palliative services earlier, and can clarify confusing behavioral changes that might otherwise be attributed to stubbornness or personality.

What Happens Inside a Centenarian’s Brain

One of the most revealing lines of dementia research in recent years involves postmortem examination of centenarian brains. A study of 100 centenarians from The 90+ Study found that 59 percent had at least four neuropathological changes at autopsy — Alzheimer’s plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, lewy bodies, vascular damage, and other markers of disease. That finding alone is arresting: more than half of these individuals, some of whom functioned reasonably well in daily life, carried significant brain pathology. It suggests that reaching 100 almost guarantees some degree of neurological damage, whether or not it manifests as clinical dementia. The incidence of dementia in centenarians runs at approximately 41 percent per year, compared to 21 percent per year in the 95 to 99 age group and 13 percent per year in the 90 to 94 group.

Those numbers reflect an acceleration that makes dementia almost an expected companion to extreme longevity. Yet there is a fascinating counterpoint: research on dementia-free survival among centenarians found that the prevalence of dementia-free survival past age 100 varies between 0 and 50 percent across different studies. Even more intriguing, the existence of cognitively healthy individuals older than 110 — so-called supercentenarians — suggests that dementia incidence may actually decelerate somewhere after age 100. Researchers do not yet understand why some brains remain resilient despite accumulating the same pathology that disables others. Genetic factors, cognitive reserve built over a lifetime, and still-unknown protective mechanisms are all under investigation.

How Families Should Approach Care Planning After a Diagnosis at 100

When a centenarian receives a dementia diagnosis, the care conversation should look fundamentally different from one held for a 72-year-old with the same diagnosis. For the younger patient, families may weigh years of gradual decline, the likelihood of nursing home placement — median time to nursing home admission after dementia diagnosis is 3.3 years according to the BMJ review — and the long arc of progressive dependency. For a centenarian, the timeline compresses. The priority shifts from managing a long disease course to ensuring that each remaining day holds as much comfort and meaning as possible. This does not mean doing nothing.

Palliative care, pain management, social engagement, and sensory stimulation all remain valuable. Music therapy, familiar voices, gentle touch, and maintaining routines can significantly improve quality of life even when cognitive function is severely impaired. The tradeoff families often face is between pursuing medical interventions — hospitalizations for infections, feeding tubes for swallowing difficulties, new medications with uncertain benefit — and accepting that the body is reaching its natural endpoint. At 100, the calculus generally favors less intervention and more comfort. Hospice eligibility typically requires a prognosis of six months or less, and many centenarians with dementia meet that threshold. Early hospice enrollment gives families access to nursing support, respite care, and bereavement counseling that can make an enormous difference during a compressed and emotionally intense final chapter.

The Limits of What Survival Statistics Can Tell Us

All the numbers cited in this article come with significant caveats. The 2024–2025 BMJ systematic review — the largest of its kind, spanning 261 studies and over 5 million people — found that overall, 90 percent of dementia patients are alive one year after diagnosis, but only 21 percent survive to 10 years. Those are population-level averages. They do not account for the enormous variation driven by dementia type, comorbid conditions, access to care, socioeconomic factors, and individual biology. Alzheimer’s disease patients, for example, survived on average 1.4 years longer than those with vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, or Lewy body dementia. The type of dementia matters, and at age 100, mixed pathology — where multiple types of brain damage overlap — is extremely common.

Another limitation: most dementia survival studies are weighted toward younger populations because centenarians are, by definition, rare. The data on dementia at age 100 is extrapolated rather than directly measured in large cohorts. Families should treat the 1.5 to 2.5 year estimate as a rough guide, not a countdown. Some centenarians with dementia stabilize for extended periods. Others experience rapid decline within weeks of diagnosis. The research from The 90+ Study showing that dementia does not significantly increase mortality at very advanced ages is reassuring in one sense — it means the diagnosis itself is not a death sentence — but it also means the underlying frailty of extreme old age is the primary driver of outcomes, and that frailty is difficult to predict on an individual level.

When Dementia Appears Very Late, Duration Tends to Be Short

Research published in PubMed on dementia-free survival among centenarians found that when dementia does occur in centenarians, it tends to be of very short duration before death. This pattern differs from the prolonged, multi-year decline seen in patients diagnosed in their 60s or 70s.

A centenarian might go from early memory complaints to severe impairment in a matter of months rather than years. For families, this compressed timeline means that advance care planning becomes urgent the moment a diagnosis is made — or ideally, well before. Having conversations about goals of care, end-of-life preferences, and legal documents like powers of attorney and advance directives should happen while the person can still participate, even in a limited way.

What Centenarian Research May Reveal About the Future of Dementia

The study of centenarians is not just about end-of-life statistics. It is opening a window into why some brains resist dementia despite carrying the same pathological markers that devastate others. The finding that 59 percent of centenarians had at least four types of neuropathological changes, yet not all were clinically demented, challenges the simplistic model that plaques and tangles equal disease.

If researchers can identify what protects some centenarian brains — whether it is genetic variants, lifelong cognitive engagement, specific immune responses, or something else entirely — the implications could reshape dementia prevention for everyone. The possibility that dementia incidence may decelerate after age 100, suggested by the existence of cognitively intact supercentenarians, adds another layer of mystery. As the global population ages and the number of centenarians grows, this research will only become more urgent and more relevant to public health planning.

Conclusion

A dementia diagnosis at age 100 carries an estimated survival of roughly 1.5 to 2.5 years, a figure that closely mirrors the baseline life expectancy at that age regardless of cognitive status. The large-scale BMJ review of 261 studies, The 90+ Study, and centenarian-specific neuropathological research all converge on a consistent finding: at extreme old age, dementia becomes less of an independent mortality risk and more of an accompaniment to the natural limits of the human body. For families, the practical takeaway is that care should prioritize comfort, dignity, and quality of life over aggressive medical intervention.

If someone you love has received a dementia diagnosis at or near age 100, the most important steps are to engage palliative or hospice services early, ensure that advance directives are in place, and focus on what brings the person comfort and connection. The numbers tell part of the story, but they cannot capture what a familiar voice, a favorite song, or a hand held in silence means to someone in their final chapter. Lean on the care team, lean on each other, and let the research inform your decisions without letting it define your experience.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is dementia inevitable if you live to 100?

Not quite, though the odds are high. The incidence of dementia in centenarians is approximately 41 percent per year, and studies show that dementia-free survival past age 100 ranges from 0 to 50 percent depending on the population studied. Some cognitively intact individuals have been documented beyond age 110, suggesting that dementia is not an absolute certainty of extreme longevity.

Does the type of dementia matter for survival at age 100?

It does at younger ages — Alzheimer’s disease patients survive on average 1.4 years longer than those with vascular, frontotemporal, or Lewy body dementia. At age 100, however, mixed pathology is extremely common, with 59 percent of centenarians showing at least four types of neuropathological changes at autopsy. The distinction between dementia types becomes less clinically meaningful at this extreme age.

Should families pursue a formal dementia diagnosis for a centenarian?

Yes. Even though survival timelines are similar with or without dementia at this age, a formal diagnosis helps guide medication decisions, opens access to hospice and palliative services, informs care planning, and helps family members understand behavioral changes. It is not about labeling — it is about giving families the tools to provide the best possible care.

How quickly does dementia progress at age 100?

Research indicates that when dementia occurs in centenarians, it tends to be of very short duration before death. The multi-year gradual decline seen in younger patients is less typical. Families should be prepared for a more compressed timeline and should prioritize advance care planning as soon as symptoms or a diagnosis emerge.

What is the chance of nursing home placement after a dementia diagnosis?

According to the BMJ systematic review, the median time to nursing home admission after a dementia diagnosis is 3.3 years, with 13 percent admitted in the first year and 57 percent by year five. For centenarians, the compressed survival timeline means nursing home placement may not occur or may happen very late in the course of the disease, with many families opting for in-home or hospice care instead.