The answer, according to the most rigorous evidence available, is neither. Moderate drinking does not protect against dementia, and the belief that it does has been debunked by a landmark 2025 study from the University of Oxford, Yale University, and the University of Cambridge. Published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, the study analyzed 559,559 adults aged 56 to 72 in observational data and drew on genetic data from 2.4 million participants using a method called Mendelian randomisation. The conclusion was blunt: any level of alcohol consumption increases dementia risk. There is no safe threshold.

For years, many people took comfort in headlines suggesting a glass of red wine with dinner might sharpen the mind or stave off cognitive decline. A retired teacher might have justified her nightly Pinot Noir as brain medicine. A doctor might have shrugged at a patient’s moderate drinking habit, citing older studies that seemed to show a protective effect. That era of ambiguity is over. The genetic analyses in the 2025 study found no protective association whatsoever, and the apparent benefits seen in earlier research were artifacts of flawed methodology. This article examines why the “moderate drinking is good for your brain” narrative persisted for so long, what the new science actually shows, how alcohol damages the brain at a biological level, what the global stakes are, and what practical steps you can take to reduce your dementia risk.

Table of Contents

- Why Did Scientists Once Think Moderate Drinking Protected Against Dementia?

- How Much Does Alcohol Actually Increase Dementia Risk?

- What Alcohol Does to the Brain at the Cellular Level

- Practical Steps to Reduce Dementia Risk Beyond Cutting Alcohol

- Why Official Dietary Guidance Has Lagged Behind the Science

- The Global Scale of the Dementia Crisis

- Where the Research Goes From Here

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Why Did Scientists Once Think Moderate Drinking Protected Against Dementia?

The idea that moderate alcohol consumption might protect the brain followed a pattern familiar from heart disease research. For decades, observational studies compared groups of drinkers and non-drinkers, then tracked who developed various diseases. Light and moderate drinkers often appeared healthier than abstainers. The problem was that the “abstainer” category included people who had quit drinking because they were already sick, people on medications incompatible with alcohol, and people with lower incomes or poorer overall health. This is known as the “sick quitter” bias, and it systematically inflated the apparent health of moderate drinkers by comparison. The 2025 Oxford-Yale-Cambridge study identified another powerful confounding factor: reverse causation. People in the early, pre-diagnostic stages of dementia often reduce their alcohol intake — sometimes years before they receive a formal diagnosis.

When researchers later compare their outcomes to those of people still drinking moderately, it looks as though cutting back on alcohol caused the dementia rather than the other way around. During the study’s follow-up period, 14,540 participants developed dementia and 48,034 died, providing a large enough sample to detect and correct for this bias. Once the researchers used genetic instruments — which are not subject to reverse causation or lifestyle confounders — the supposed protective effect vanished entirely. A separate 2025 study published in Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience confirmed this from a different angle. It found that the previously reported “protective” associations between moderate drinking and cognition are an artifact of income, language proficiency, and cultural factors. When socioeconomic variables were properly controlled, the benefit disappeared. In other words, moderate drinkers tended to be wealthier and better educated, and it was those advantages — not the alcohol — that correlated with better cognitive performance.

How Much Does Alcohol Actually Increase Dementia Risk?

The numbers from the 2025 BMJ study are specific and sobering. A one standard deviation increase in log-transformed drinks per week was associated with a 15 percent increase in dementia risk. A twofold increase in genetically predicted alcohol use disorder prevalence was linked to a 16 percent higher dementia risk. These are not negligible margins. Researchers estimated that reducing alcohol use disorder prevalence could prevent up to 16 percent of dementia cases — a staggering number when you consider the scale of the disease worldwide. However, a limitation worth noting is that these findings are strongest for the population studied: adults aged 56 to 72, predominantly of European ancestry. The Mendelian randomisation approach relies on genetic variants that affect alcohol metabolism, and these variants differ across populations.

While there is no credible reason to believe alcohol would be protective in other groups, the precise risk percentages may not translate directly to every demographic. Younger adults, for example, may face different patterns of cumulative harm depending on when and how heavily they drink across their lifetimes. It is also important to distinguish between risk at the population level and risk for any single individual. A 15 percent increase in relative risk does not mean a given person has a 15 percent chance of developing dementia. It means that across a large group, the rate of dementia is 15 percent higher among those who drink more. Individual risk depends on genetics, overall health, cardiovascular fitness, diet, education, social engagement, and many other factors. But the direction of the evidence is unambiguous: more alcohol means more risk, with no safe floor.

What Alcohol Does to the Brain at the Cellular Level

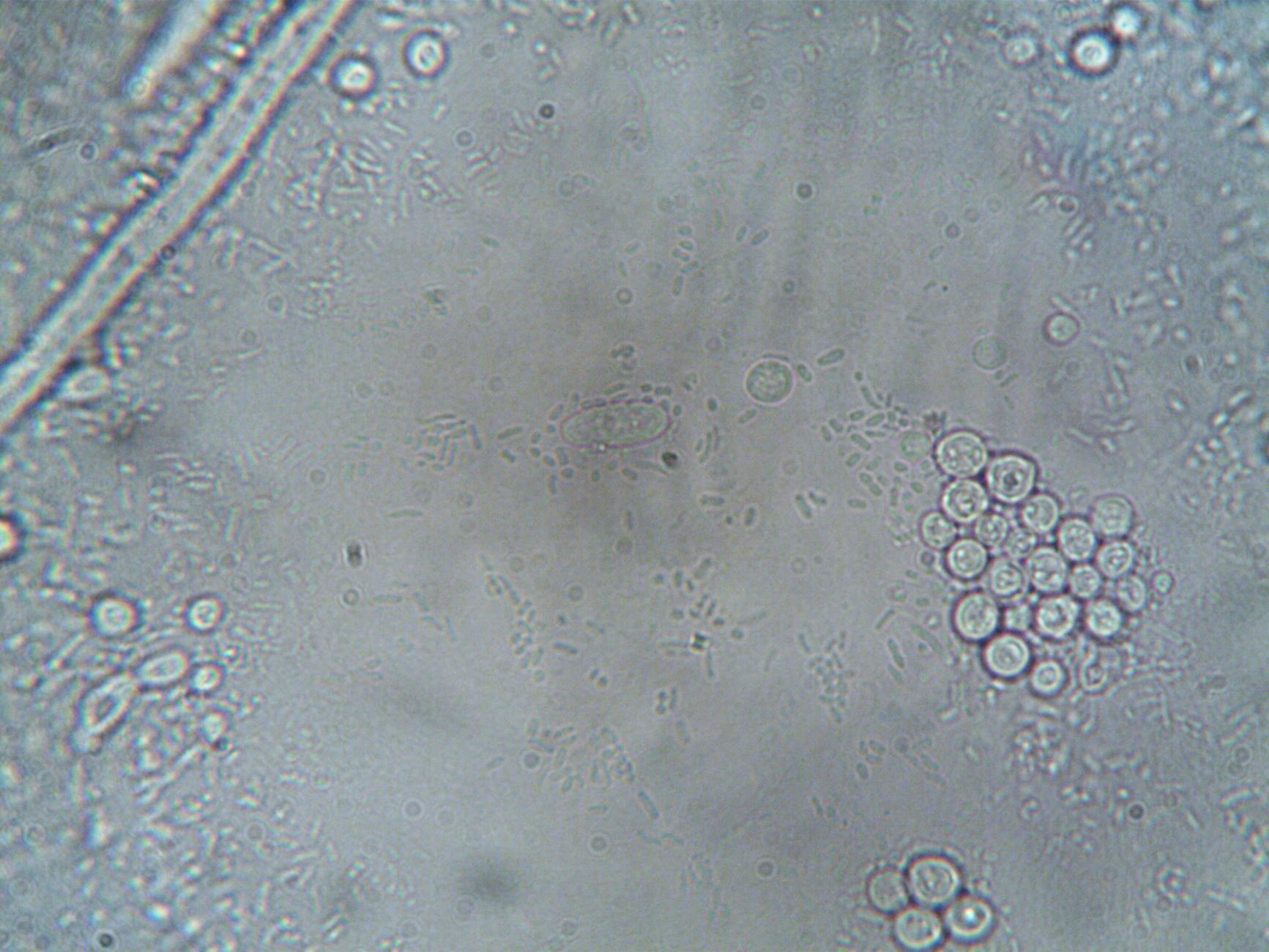

The damage alcohol inflicts on the brain is not limited to the well-known effects of heavy, chronic drinking. Neuropathological research has found that moderate, heavy, and even former heavy alcohol consumption are all associated with hyaline arteriolosclerosis — a thickening and hardening of small blood vessels in the brain — and with neurofibrillary tangles, one of the defining hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. These are not abstract biomarkers. They represent physical destruction of the brain’s infrastructure, the kind of damage visible under a microscope in postmortem tissue. At a broader structural level, alcohol disrupts both gray matter and white matter, reduces overall brain volume, impairs myelin regeneration — myelin being the insulating sheath that allows neurons to communicate efficiently — and increases iron accumulation in the brain.

Excess iron has been linked to both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Consider what this means for someone who drinks moderately over 30 or 40 years: they may never experience an episode of acute intoxication severe enough to alarm anyone, yet their brain is gradually losing volume, accumulating iron, and developing the vascular damage and protein tangles associated with dementia. A person in their 40s who drinks two glasses of wine most evenings might feel cognitively sharp and assume no harm is being done. But the brain changes associated with chronic moderate consumption are largely silent until they cross a clinical threshold. By the time symptoms of cognitive decline become noticeable, substantial and irreversible damage has already occurred.

Practical Steps to Reduce Dementia Risk Beyond Cutting Alcohol

Reducing or eliminating alcohol consumption is one of the most direct steps a person can take to lower dementia risk, but it does not exist in isolation. The WHO’s 2019 guidelines on risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia identified alcohol use disorders as a modifiable risk factor, finding significant dementia association starting at approximately 38 grams per day — roughly three standard drinks. But the 2025 evidence suggests harm begins well below that threshold, which means the practical advice has shifted from “drink in moderation” to “drink as little as possible.” The tradeoff many people weigh is social and psychological. Alcohol is deeply embedded in social rituals, stress relief, and cultural identity. Telling someone to stop drinking entirely may be medically sound but socially unrealistic for many.

A more effective approach for most people is gradual reduction combined with substitution — replacing alcohol with other social rituals, finding alternative stress-management tools, and reframing the habit. The Alzheimer’s Society in the UK advises that drinking alcohol increases dementia risk and recommends limiting intake as much as possible, a position that avoids absolutism while being clear about the direction of the evidence. Other modifiable risk factors for dementia include physical inactivity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, social isolation, depression, and hearing loss. Addressing several of these simultaneously is likely more impactful than focusing on any single one. But alcohol is worth particular attention because, unlike some risk factors, its reduction requires no medical intervention, no prescription, and no equipment — only a decision.

Why Official Dietary Guidance Has Lagged Behind the Science

One of the more frustrating aspects of the alcohol-dementia story is how slowly public health guidance has caught up to the evidence. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases raised concerns over the removal of evidence-based alcohol guidance from the 2025-2030 U.S. Dietary Guidelines. This means that the official dietary framework guiding American health policy was weakened on alcohol at precisely the moment when the scientific consensus was hardening against it. This gap between evidence and policy is not unique to the United States, but it matters enormously.

When official guidelines suggest that moderate drinking is acceptable or even beneficial, they provide cover for an industry that profits from consumption and for individuals who would prefer not to change their habits. The 2025 Oxford-Yale-Cambridge study should serve as a corrective, but its impact depends on whether policymakers, physicians, and public health communicators actually incorporate its findings into their recommendations. A warning for consumers: the absence of a guideline is not the same as a green light. If your country’s dietary guidelines do not explicitly address alcohol and dementia risk, that does not mean moderate drinking is safe. It means the guidelines have not yet been updated. The science is ahead of the policy, and the science is clear.

The Global Scale of the Dementia Crisis

The stakes of this research are enormous. According to the World Health Organization, more than 55 million people worldwide currently live with dementia, and there are nearly 10 million new cases every year. Dementia is the seventh leading cause of death globally. Any modifiable risk factor that could prevent even a fraction of those cases demands serious attention.

The 2025 estimate that reducing alcohol use disorder prevalence could prevent up to 16 percent of dementia cases translates, at global scale, to potentially hundreds of thousands of prevented cases annually. To put that in concrete terms: if a mid-sized country like Australia, with roughly 400,000 people living with dementia, could reduce alcohol-attributable cases by even half of that 16 percent estimate, it would mean tens of thousands of people retaining their independence, their memories, and their identities. That is not a marginal public health gain. It is transformative.

Where the Research Goes From Here

The 2025 studies represent a turning point, but they are not the final word. Future research will need to clarify dose-response relationships at very low levels of consumption, examine how alcohol interacts with specific genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease, and determine whether the timing of alcohol exposure across the lifespan matters — whether drinking heavily in your 20s and stopping, for example, carries a different long-term risk than moderate lifelong consumption.

What is unlikely to change is the central finding: the era of recommending moderate alcohol as brain-protective is over. The Mendelian randomisation evidence is methodologically robust in ways that observational studies never were, and it points in one direction. For anyone concerned about dementia — whether for themselves, a parent, or a partner — the most prudent course is to treat alcohol as a risk factor to be minimized, not a medicine to be prescribed.

Conclusion

The belief that moderate drinking protects against dementia was one of the most persistent and comforting myths in public health. It persisted because of flawed study designs that failed to account for reverse causation, socioeconomic confounders, and the sick-quitter bias. The 2025 research from Oxford, Yale, and Cambridge — using genetic analysis to strip away these confounders — has dismantled that belief. Any level of alcohol consumption increases dementia risk.

The mechanisms are well-documented: brain volume loss, white matter damage, impaired myelin regeneration, iron accumulation, small vessel disease, and neurofibrillary tangles. For individuals, the practical takeaway is straightforward: reduce alcohol intake as much as possible, especially if you have other dementia risk factors. For policymakers, the task is to update dietary guidelines and public health messaging to reflect the current evidence, not the outdated assumptions of earlier decades. With more than 55 million people living with dementia worldwide and nearly 10 million new cases each year, there is no justification for clinging to a debunked narrative that may be contributing to preventable suffering.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is one glass of wine per day safe for brain health?

According to the 2025 Oxford-Yale-Cambridge study, no level of alcohol consumption was found to be safe for dementia risk. While one glass per day represents lower risk than heavier drinking, the genetic evidence shows no threshold below which alcohol becomes protective or neutral.

Does the type of alcohol matter — is red wine better than beer or spirits?

The 2025 research did not find a meaningful difference based on beverage type. The active ingredient driving brain harm is ethanol, which is present in all alcoholic drinks. The antioxidants in red wine, while real, do not offset the neurotoxic effects of the alcohol itself, and those same antioxidants are available in grape juice, berries, and other foods without the associated risks.

If I used to drink heavily but have stopped, is the damage permanent?

Neuropathological research found that former heavy alcohol consumption was still associated with small blood vessel disease and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. However, stopping alcohol use eliminates the ongoing source of harm, and the brain does have some capacity for recovery over time. Quitting is still one of the most beneficial decisions a former heavy drinker can make.

I have a family history of dementia. Should I stop drinking entirely?

A family history of dementia means you may already carry elevated genetic risk. Adding alcohol — a confirmed modifiable risk factor — on top of genetic predisposition is a choice that increases cumulative risk. While no study can tell you exactly what will happen to any individual, minimizing or eliminating alcohol is one of the few risk-reduction steps entirely within your control.

Why do some doctors still say moderate drinking is fine?

Medical education and clinical guidelines often lag behind the latest research by years. Many physicians were trained during an era when observational studies appeared to show a protective effect of moderate drinking. The 2025 Mendelian randomisation studies are relatively new, and it takes time for findings to filter into clinical practice and updated guidelines.