Yes, retinal scans can detect signs of Alzheimer’s disease before symptoms appear — and the evidence for this has grown substantially in recent years. The retina, which is essentially an extension of brain tissue, accumulates the same amyloid-beta plaques that characterize Alzheimer’s in the brain, and measurable changes in retinal blood vessels have been observed in people who carry the APOE-E4 genetic risk factor but show no cognitive symptoms whatsoever. Researchers at Hebrew SeniorLife described this as “the first time demonstrated in living, asymptomatic humans” — a finding that underscores just how early these retinal changes may begin. The technology is not yet available as a routine clinical screening tool, but it is advancing rapidly across multiple research fronts.

What makes this development significant is the potential to shift Alzheimer’s care from reactive to preventive. Current diagnosis typically happens after years of cognitive decline, when neurological damage is already extensive. A non-invasive eye scan that could flag at-risk individuals a decade before memory loss begins would fundamentally change what is possible in terms of intervention. This article covers the biological basis for retinal scanning as a detection method, the accuracy of current AI-assisted tools, the state of active clinical research, and what people can realistically expect in terms of when this technology might reach everyday medical practice.

Table of Contents

- How Can a Retinal Scan Detect Alzheimer’s Before Symptoms Appear?

- What Do the AI Detection Accuracy Numbers Actually Mean?

- Active Research Programs Pushing Toward Clinical Use

- How Does Retinal Scanning Compare to Existing Alzheimer’s Detection Methods?

- Limitations That Still Need to Be Resolved

- What the APOE-E4 Findings Mean for At-Risk Families

- Where This Research Is Heading Over the Next Decade

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Can a Retinal Scan Detect Alzheimer’s Before Symptoms Appear?

The connection between the eye and Alzheimer’s disease is not metaphorical — it is anatomical. The retina is made up of neurons that are a direct extension of the central nervous system, sharing developmental origins with the brain. Because of this, the amyloid-beta protein that accumulates abnormally in Alzheimer’s disease also deposits in the retina, following the same pattern seen in brain tissue. This makes the eye a uniquely accessible window for detecting pathology that would otherwise require an invasive spinal tap or an expensive PET brain scan to identify.

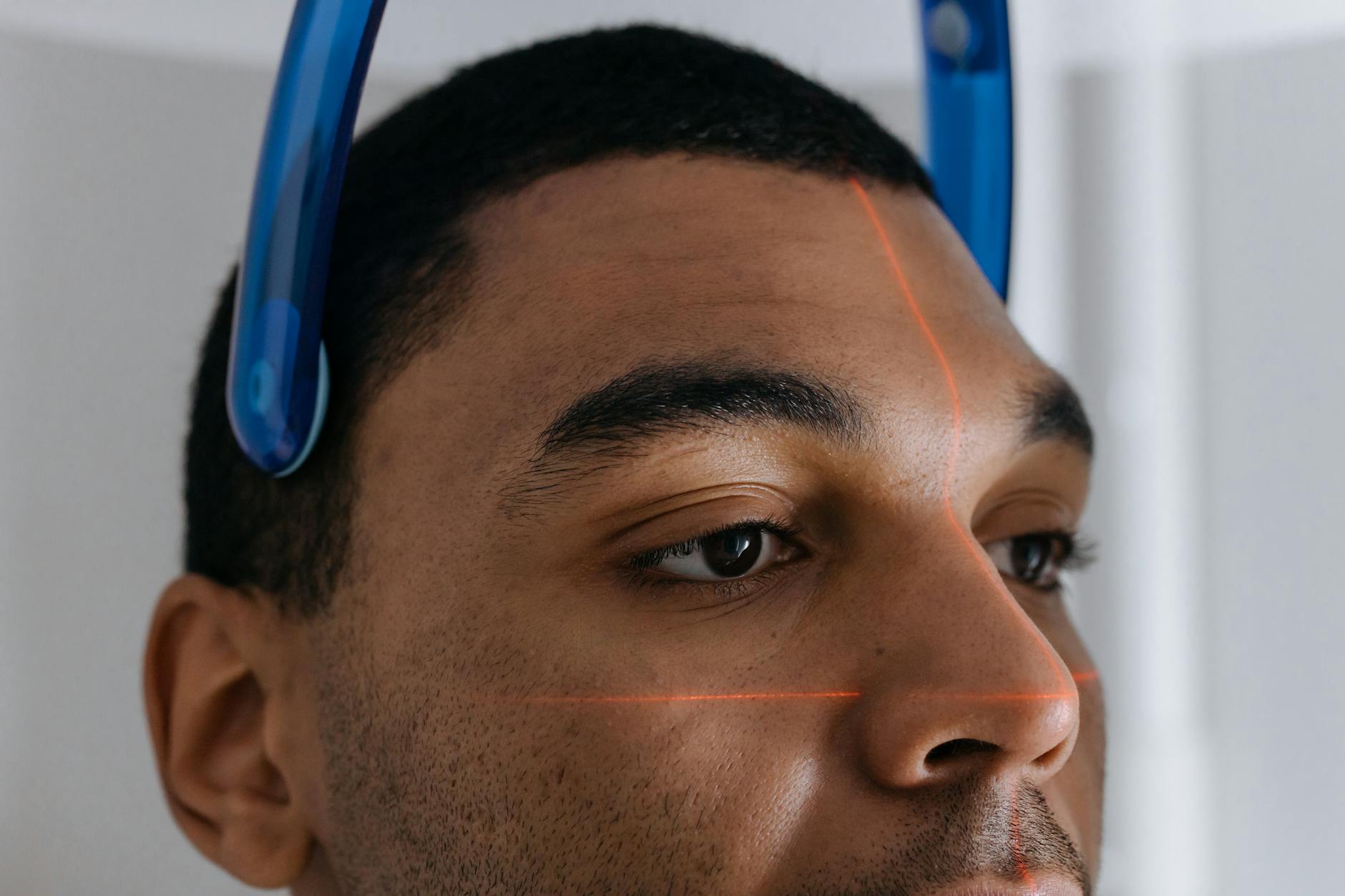

Beyond amyloid plaques, researchers have identified changes in the retina’s microvasculature — its tiny network of blood vessels — that appear in people at genetic risk for Alzheimer’s long before any cognitive symptoms emerge. In studies of individuals carrying the APOE-E4 gene, which is the most significant known genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s, these vascular changes were detectable through imaging techniques like optical coherence tomography angiography, or OCTA. This technology creates detailed, three-dimensional maps of blood flow in the eye without requiring dye injections or physical contact with the eye itself. Think of it as an mri for the retina — precise, non-invasive, and increasingly capable of detecting subtle disease-related changes.

What Do the AI Detection Accuracy Numbers Actually Mean?

The research data on AI-assisted retinal scanning is encouraging, but interpreting it requires some care. In January 2025, a deep learning tool called EyeAD, developed using OCTA images, was published in the journal npj Digital Medicine. For detecting early-onset Alzheimer’s, it achieved an AUC — area under the curve, a standard measure of diagnostic accuracy — of 0.9355 in internal testing and 0.9007 on external validation data. An AUC of 1.0 would represent perfect accuracy; 0.5 would be no better than a coin flip. Scores above 0.90 are considered excellent in diagnostic medicine. EyeAD also showed a meaningful ability to detect mild cognitive impairment, a precursor state to Alzheimer’s, with an AUC of 0.8630 internally and 0.8037 externally.

A separate research program using tri-spectral retinal imaging and a machine learning model reported 91% accuracy in distinguishing Alzheimer’s patients from healthy controls. A broader meta-analysis published in 2025 by ScienceDirect, which pooled results across multiple studies, found a more moderate overall AUC of 0.726, with OCT-specific approaches reaching 0.762. The gap between the best single-study results and the meta-analysis average is important. It reflects the reality that individual studies are often conducted under controlled conditions with carefully selected participants, while real-world performance across diverse populations tends to be lower. The headline figures are promising; the meta-analysis figures are what practitioners should bear in mind when assessing clinical readiness. However, even a tool with an AUC in the 0.75 to 0.80 range could be clinically useful as a low-cost first-pass screening method, flagging individuals who warrant more definitive follow-up testing. It would not need to be perfect to add genuine value, particularly in settings where access to PET scans or cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing is limited by cost or availability.

Active Research Programs Pushing Toward Clinical Use

Several well-funded research programs are actively working to close the gap between laboratory findings and clinical deployment. Oregon Health and Science University is developing an approach that adds a biochemical detection layer on top of standard retinal imaging. Patients apply an eye drop containing a fluorescent molecule that binds specifically to amyloid deposits in the retina. Under the right imaging conditions, these deposits then emit a detectable signal, making the amyloid visible rather than inferred from structural changes alone. This work is supported by a $3.3 million, five-year federal research award — a level of institutional funding that indicates serious scientific confidence in the approach.

The University of Minnesota has taken a different angle, developing a low-cost, non-invasive imaging camera designed for broader clinical and even community deployment. The goal is a device that could eventually be placed in primary care offices or optometry clinics — settings where many people have routine eye exams already — making large-scale screening logistically feasible. Separately, a clinical trial conducted at a Swedish memory clinic between January 2023 and May 2024 enrolled 57 patients using hyperspectral retinal imaging. The best model from that trial achieved an AUC of 0.77, with accuracy of 0.66 and sensitivity of 0.73 — results that are modest by the standards of the controlled AI studies but represent real-world memory clinic performance, which is a more honest test of clinical utility. A January 2026 study using label-free optical methods — meaning no dyes, contrast agents, or eye drops — reported detection of early Alzheimer’s signs through what researchers described as a fully non-invasive eye scan. While full peer-reviewed details of that study are still emerging, the direction of travel is consistent across multiple independent research groups: toward non-invasive, accessible, low-burden screening that could be integrated into existing medical infrastructure.

How Does Retinal Scanning Compare to Existing Alzheimer’s Detection Methods?

The current gold standards for detecting Alzheimer’s before symptoms are fully present involve either amyloid PET imaging — a brain scan that uses a radioactive tracer — or analysis of cerebrospinal fluid obtained through a lumbar puncture. Both are accurate. Both are also expensive, invasive, or both. A PET scan can cost several thousand dollars and is not covered by standard insurance for asymptomatic screening. A lumbar puncture, while generally safe, is uncomfortable and carries a small risk of complications. Neither is suitable for widespread population-level screening. Blood-based biomarker tests, particularly assays measuring plasma phospho-tau 217, have emerged as a promising middle ground and are already being used in research settings and some specialist clinics.

These tests require only a blood draw and are significantly cheaper than imaging. The retinal scan approach would compete in a similar space — low cost, low burden, integrable into routine care — but with the added advantage that optometry visits are already a common part of preventive health for many people. Someone who would never proactively seek a dementia screening test might be scanned during a routine eye exam, making the population reach potentially broader than blood-based approaches alone. The tradeoff at this stage is accuracy and standardization. Blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s are further along in terms of clinical validation and regulatory review. Retinal imaging is more variable across different devices, imaging protocols, and AI models. For a physician advising a patient today, a blood-based phospho-tau test is likely more actionable than a retinal scan. In five years, that comparison may look different.

Limitations That Still Need to Be Resolved

The peer-reviewed literature is clear about the limitations, and it would be misleading to describe retinal scanning as a solved problem. Study sample sizes have been consistently small — the Swedish clinical trial had 57 participants, and many of the AI studies involve hundreds rather than thousands of subjects. This matters because rare subgroups, demographic variation, and co-occurring eye conditions (diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, macular degeneration) can all affect retinal imaging in ways that may confound Alzheimer’s-related signals. None of the current models have been validated in populations large enough to confidently assess performance across these variables. There is also no consensus on which specific retinal biomarker or combination of biomarkers should serve as the clinical standard. Different research groups are measuring different things — amyloid deposits, vascular density, nerve fiber layer thickness, retinal blood flow — and the field has not yet converged on a unified protocol.

This lack of standardization means that results from one study cannot always be compared directly to another, and that building a regulatory pathway for clinical approval is complicated. A diagnostic test seeking FDA clearance or CE marking in Europe needs a clearly defined biomarker target and a reproducible, standardized measurement approach. A warning for anyone reading about this technology in the popular press: headlines describing retinal scanning as already capable of “predicting” Alzheimer’s sometimes conflate research findings with clinical capability. The research findings are real. The clinical deployment is not yet. If someone approaches their optometrist today asking for an Alzheimer’s retinal scan, that test does not exist in routine clinical practice. The honest message is that it may exist within the next decade, and the scientific groundwork being laid right now makes that timeline plausible.

What the APOE-E4 Findings Mean for At-Risk Families

One of the more striking findings in the recent literature involves people who carry the APOE-E4 gene variant but have no symptoms and no diagnosis. Retinal vascular changes — specifically in the microvasculature mapped by OCTA imaging — were detected in these asymptomatic individuals, marking what researchers described as a first-in-kind demonstration of this phenomenon in living humans. This is significant because APOE-E4 is relatively common — roughly one in five people carry at least one copy of the variant — and individuals who are aware of their carrier status often have no reliable way to monitor whether disease processes have begun.

For families with a strong history of Alzheimer’s, particularly those who have pursued genetic testing, the prospect of a non-invasive retinal scan that could detect early pathological changes is psychologically and medically meaningful. It would not change genetic risk, but it could inform decisions about lifestyle interventions, clinical trial eligibility, or the timing of advance care planning discussions. This is an area where the personal stakes of the research are particularly high, and where clinical availability — even as a specialist test — cannot come soon enough for many families.

Where This Research Is Heading Over the Next Decade

The convergence of several trends makes it reasonable to expect meaningful clinical progress in retinal-based Alzheimer’s detection within the next five to ten years. AI models are improving rapidly, training datasets are growing, and imaging hardware is becoming cheaper and more accessible. Longitudinal studies that follow patients from retinal scan to eventual diagnosis are underway, and their data will ultimately provide the validation evidence needed for regulatory approval. Federal funding — exemplified by the $3.3 million award to OHSU — signals that this is a priority area within Alzheimer’s research infrastructure.

It is also worth noting that the broader Alzheimer’s detection landscape is becoming more competitive and more capable simultaneously. Blood biomarkers, digital cognitive assessments, and genetic risk scoring are all maturing at the same time. The most clinically useful approach is likely to be a combination: a multi-modal screening protocol that integrates retinal findings with blood biomarkers and brief cognitive tests, with more invasive or expensive confirmatory testing reserved for those who screen positive on multiple indicators. Retinal scanning would not need to stand alone to be valuable; it would need to add information that improves overall detection accuracy at a cost and burden level that makes population screening realistic.

Conclusion

The scientific case for retinal scanning as a pre-symptomatic Alzheimer’s detection tool is now well-established at the research level. The retina accumulates the same amyloid-beta plaques as the brain, vascular changes are detectable in asymptomatic high-risk individuals, and AI models analyzing retinal images have achieved AUC scores above 0.90 in controlled settings as of early 2025. Multiple independent research programs — including those at OHSU, the University of Minnesota, and institutions in Sweden — are actively advancing this work toward clinical application. The science is not speculative; it is in the validation phase.

What remains is the harder work of standardization, large-scale validation, and regulatory approval. For people living with family risk today, the message is that this technology is coming, the research behind it is credible, and it may eventually transform routine eye care into a frontline tool for brain health monitoring. In the meantime, staying current with developments in blood-based biomarkers and discussing genetic risk with a physician are the most actionable steps available. The eye may well become the most accessible window we have into one of medicine’s most difficult diseases — but that window is still being opened.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is retinal scanning for Alzheimer’s available at my eye doctor’s office right now?

No. Retinal scanning for Alzheimer’s detection is currently a research tool, not a standard clinical service. Optometrists and ophthalmologists use retinal imaging for eye health, but no commercially approved or widely deployed test exists specifically for Alzheimer’s screening as of early 2026.

Which retinal imaging technology is most promising for Alzheimer’s detection?

Several approaches are under investigation. OCTA (optical coherence tomography angiography) has produced some of the strongest AI accuracy results, including the EyeAD model’s AUC of 0.9355. Hyperspectral imaging and fluorescent amyloid-binding eye drops are also being actively developed. No single method has yet been designated as the clinical standard.

How accurate are current retinal scan tests for Alzheimer’s?

In controlled research settings, the best AI models have achieved accuracy around 91% and AUC scores above 0.90 for early-onset Alzheimer’s. However, a meta-analysis pooling results across multiple studies found a more moderate overall AUC of 0.726, which better reflects performance across varied real-world conditions.

If I carry the APOE-E4 gene, should I ask about retinal scanning?

This is worth discussing with a neurologist or genetic counselor, but retinal scanning is not yet a standard clinical option even for high-risk individuals. Research has shown that retinal vascular changes can be detected in asymptomatic APOE-E4 carriers, but this technology is not ready for routine clinical use outside of research enrollment.

What are the main obstacles to clinical deployment?

The key challenges are small study sample sizes, lack of standardization across imaging methods, no consensus on which retinal biomarker is most clinically relevant, and the absence of large longitudinal validation studies linking retinal findings to confirmed Alzheimer’s diagnoses. These are solvable problems, but they require time and coordinated research effort.

How does retinal scanning compare to blood tests for early Alzheimer’s detection?

Blood-based biomarkers — particularly plasma phospho-tau 217 — are currently further along in clinical validation and are already being used in some specialist settings. Retinal scanning offers a potential advantage in accessibility (integration with routine eye care), but requires more standardization and validation before it can reach comparable clinical adoption.