Your gut bacteria are directly involved in Alzheimer’s disease — and the evidence now suggests they play a role far earlier than most people realize. A 2022 study published in Science Translational Medicine examined 164 cognitively normal individuals and found that gut microbiome composition correlated with amyloid-beta and tau pathological biomarkers in people who had no cognitive symptoms whatsoever. In other words, shifts in your intestinal bacteria may be detectable markers of Alzheimer’s pathology years before memory loss begins. Specific species like Bacteroides intestinalis, Dorea formicigenerans, and Ruminococcus lactaris were more abundant in those with preclinical Alzheimer’s biomarkers, and when researchers added microbiome data to machine learning classifiers, prediction accuracy for preclinical Alzheimer’s status improved.

This matters because Alzheimer’s currently affects 7.2 million Americans age 65 and older, with projections reaching 13.8 million by 2060. Globally, over 50 million people live with dementia, a number expected to balloon to 139 million by 2050. Every 3.2 seconds, someone in the world develops dementia. The scale of the crisis demands new approaches — and the gut-brain axis is emerging as one of the most promising frontiers. This article covers the biological mechanisms connecting your microbiome to your brain, which bacteria appear harmful or protective, what clinical trials are showing about probiotics and other gut-targeted therapies, dietary strategies backed by research, and the honest limitations of what we know so far.

Table of Contents

- How Do Gut Bacteria Actually Affect Your Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease?

- Which Gut Bacteria Are Linked to Alzheimer’s Risk?

- Probiotics, Fecal Transplants, and Gut-Targeted Alzheimer’s Treatments in Clinical Trials

- What Should You Eat to Support Your Gut-Brain Connection?

- What the Research Still Cannot Tell Us

- The Microbiome as an Early Detection Tool

- Where Gut-Brain Alzheimer’s Research Goes From Here

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Gut Bacteria Actually Affect Your Brain in Alzheimer’s Disease?

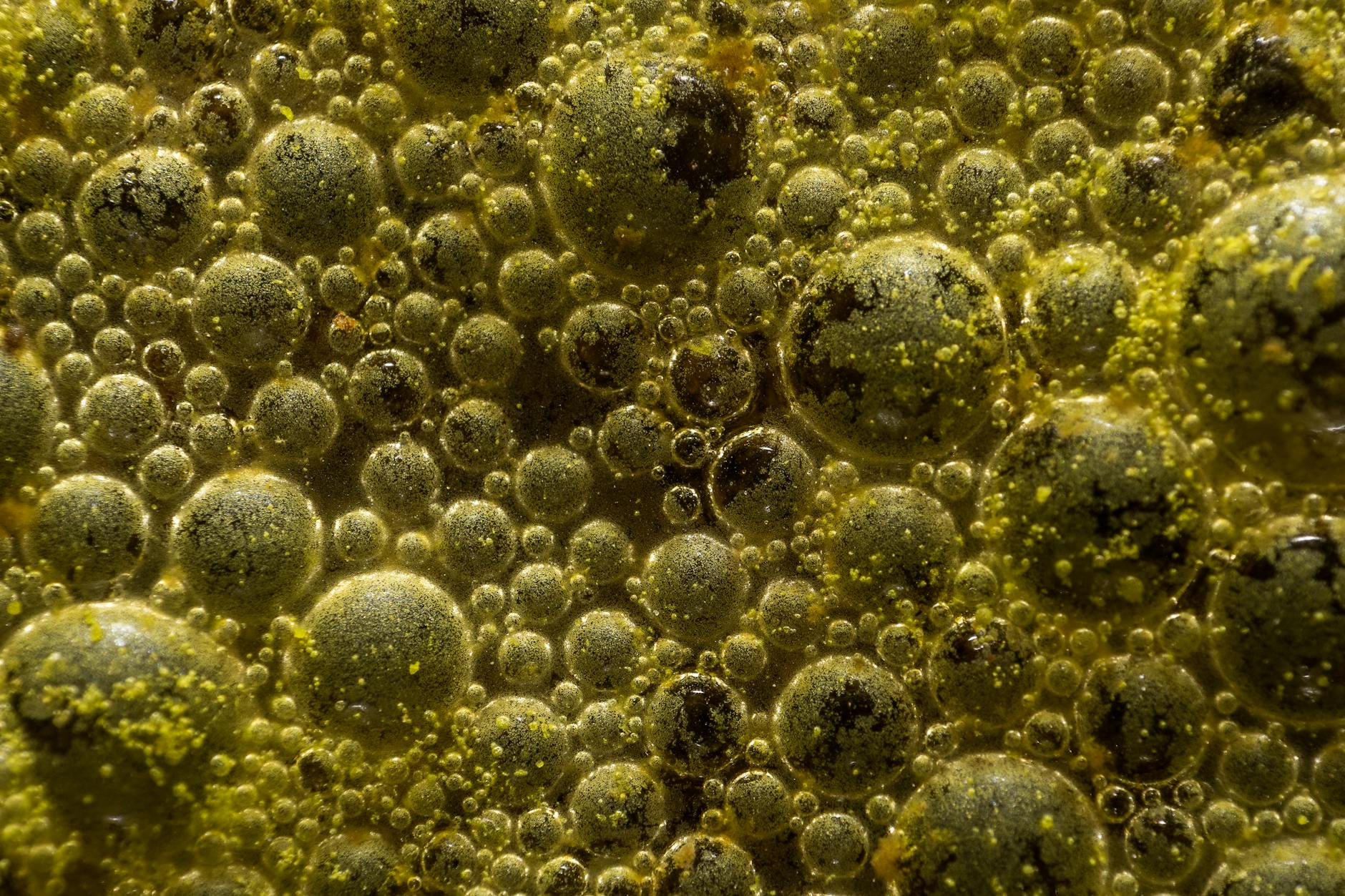

The connection between your intestines and your brain runs through several concrete biological pathways. Gut microbiome disruptions impair intestinal barrier stability, alter immune responses, and change blood-brain barrier permeability through microbial metabolite-mediated pathways. When the gut lining breaks down — sometimes called “leaky gut” — bacterial products and inflammatory molecules enter the bloodstream and eventually reach the brain, where they can trigger or worsen neuroinflammation. Research published in Molecular Psychiatry in 2025 found that over 10 percent of microbial species and gene families show significant alterations during Alzheimer’s progression, linked specifically to neuroinflammation and neurotransmitter dysregulation. One of the most striking findings came from Northwestern University in June 2025.

Researchers discovered that propionate, a short-chain fatty acid naturally produced by gut bacteria during fiber fermentation, lowers IL-17 — a key inflammatory marker — and reduces both amyloid plaques and tau accumulation in Alzheimer’s model mice. Think of propionate as a chemical messenger your gut bacteria send to your brain, and when the right bacteria are present and well-fed, that message tells the brain’s immune system to calm down. When those bacteria are absent or outnumbered, the message never arrives. It is worth noting a critical distinction the Science Translational Medicine study made: gut microbiome changes correlated with amyloid and tau pathology but not with neurodegeneration markers. This suggests that the microbiome’s influence may be most relevant in the earliest stages of the disease — during the buildup of toxic proteins — rather than during the later phase when neurons are actively dying. That distinction matters for anyone thinking about prevention versus treatment, because it implies there may be a window where gut-targeted interventions could have the greatest impact.

Which Gut Bacteria Are Linked to Alzheimer’s Risk?

Not all bacteria carry the same weight when it comes to brain health. A 2025 review in Frontiers in Immunology identified several species implicated in Alzheimer’s development, including Fusobacterium rectum and Porphyromonas gingivalis — the latter being the same bacterium associated with chronic gum disease, which has its own independent link to dementia risk. Certain strains of Lactobacillus rhamnosus, a species commonly found in commercial probiotics, have also been implicated, which serves as a reminder that even “good” bacteria can behave differently depending on the strain and context. On the protective side, Bifidobacterium infantis has demonstrated support for neuroimmune responses and offers protection against neuroinflammation. The preclinical Alzheimer’s study identified Blautia obeum, Barnesiella intestinihominis, and Anaerostipes hadrus among species that were more abundant in participants with early Alzheimer’s biomarkers — though abundance does not necessarily mean causation.

Some of these species may be responding to the disease environment rather than driving it. However, if you are tempted to simply look up which probiotics contain “good” strains and avoid “bad” ones, the reality is more complicated. The same bacterial species can behave differently depending on the broader microbial community it lives in, what you eat, your genetic background, and other medications you take. A strain of Lactobacillus rhamnosus in one person’s gut may function entirely differently than the same strain in another person’s. The field has not yet reached the point where clinicians can prescribe a specific bacterial cocktail tailored to individual Alzheimer’s risk. What the research does tell us is that overall microbial diversity and balance matter more than any single species.

Probiotics, Fecal Transplants, and Gut-Targeted Alzheimer’s Treatments in Clinical Trials

Several gut-focused treatments have moved beyond animal models and into human trials, with mixed but encouraging results. A 2025 umbrella review of randomized controlled trials, published in npj Dementia by Nature, found that multi-strain probiotic supplementation improved global cognition and memory in patients with Alzheimer’s and mild cognitive impairment. The key word is “multi-strain” — single-strain probiotics have generally shown weaker and less consistent results, suggesting that microbial diversity in the supplement matters just as it does in the gut itself. One specific probiotic, Clostridium butyricum, has demonstrated efficacy in preclinical and early clinical settings by restoring gut balance and suppressing neuroinflammatory cascades. Meanwhile, the most advanced gut-targeted Alzheimer’s drug is GV-971, also called sodium oligomannate, which is derived from marine algae and works by reshaping the gut microbiota.

It was approved in China in 2019 and showed significant cognitive improvement sustained over a 36-week Phase 3 trial. Northwestern’s propionate research has also moved toward clinical application — a 12-week probiotic supplementation investigation in preclinical Alzheimer’s patients was conducted, with researchers identifying boosting propionate levels through diet, probiotics, or medication as a potential strategy to slow disease progression. Perhaps the most dramatic intervention under investigation is fecal microbiota transplantation, in which a healthy donor’s gut bacteria are transferred to an Alzheimer’s patient. Early-phase FMT trials reported cognitive improvements in 2025. The concept sounds unpalatable to many, but it represents the most direct way to overhaul a damaged microbiome. For a person whose grandmother was just diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, these trials represent genuine reason for cautious optimism — not a cure, but a growing body of evidence that the gut is a viable therapeutic target.

What Should You Eat to Support Your Gut-Brain Connection?

Dietary patterns have emerged as one of the most accessible ways to influence the gut microbiome, and by extension, brain health. The Mediterranean diet — rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, olive oil, fish, and legumes — has been linked to decreased neuroinflammation and enhanced gut-brain communication in the context of Alzheimer’s, according to a 2025 review in Frontiers in Nutrition. This dietary pattern feeds beneficial bacteria that produce short-chain fatty acids like propionate and butyrate, which in turn support intestinal barrier integrity and reduce systemic inflammation. Polyphenols, found in foods like berries, dark chocolate, green tea, and red wine in moderation, have demonstrated efficacy in restoring gut balance and enhancing intestinal barrier integrity in preclinical Alzheimer’s models. Physical exercise has shown similar benefits — not as a food, obviously, but as a complementary lifestyle factor that independently improves microbial diversity.

The tradeoff worth understanding is between dietary approaches and supplement approaches. A Mediterranean-style diet offers broad microbial support with virtually no downside risk, but the changes it produces in the microbiome are gradual and modest. Probiotic supplements can deliver high concentrations of specific strains quickly, but the umbrella review noted that study heterogeneity remained high — meaning results vary considerably from trial to trial and person to person. For most people, the dietary approach is the safer foundation, with probiotics considered as a potential addition rather than a replacement. Nobody has ever been harmed by eating more vegetables and fiber, while the long-term effects of specific probiotic strains in aging brains remain under investigation.

What the Research Still Cannot Tell Us

For all the progress in understanding the gut-brain axis in Alzheimer’s, the field faces significant limitations that anyone following this research should understand. A 2025 review in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences identified several critical constraints: overreliance on animal models with limited translatability to humans, short-term intervention studies that cannot capture the decades-long progression of Alzheimer’s, and a critical lack of large-scale standardized human trials. A separate scoping review published in PMC in 2025 reinforced this assessment, noting that probiotic and dietary interventions show promise but results remain inconsistent across studies. The authors called for standardized protocols, functional microbiome analysis that goes beyond simply cataloging which species are present, and longitudinal human studies that follow participants for years rather than weeks. Most probiotic trials to date have lasted 12 weeks or less — a meaningful timeframe for measuring short-term cognitive changes, but inadequate for understanding whether those changes persist or accumulate over the years it takes Alzheimer’s to progress.

There is also an important warning for consumers: the probiotic supplement market is enormous and largely unregulated. Many products on store shelves contain strains that have never been tested in the context of Alzheimer’s or cognitive decline. Some contain strains that, as noted earlier, may actually be implicated in disease processes depending on the context. Taking a random probiotic because you read that “gut bacteria affect Alzheimer’s” is not the same as participating in a controlled clinical trial with carefully selected strains at specific doses. Until the research matures, broad dietary strategies remain more evidence-based than targeted supplementation for most people.

The Microbiome as an Early Detection Tool

One of the most practical near-term applications of gut-brain research may not be treatment at all — it may be diagnosis. The Science Translational Medicine study showed that including microbiome features improved machine learning classifiers for predicting preclinical Alzheimer’s status when tested on 65 of the 164 participants. A stool sample is far less invasive and expensive than a PET scan or lumbar puncture, the current gold standards for detecting amyloid and tau pathology in the brain.

Imagine a future where a routine stool analysis at your annual physical could flag elevated Alzheimer’s risk the same way a blood lipid panel flags cardiovascular risk. We are not there yet — the classifiers need validation in larger and more diverse populations — but the principle has been demonstrated. For families with a strong history of Alzheimer’s, this line of research offers something that has been in short supply: the possibility of early warning, at a stage when interventions might still make a meaningful difference.

Where Gut-Brain Alzheimer’s Research Goes From Here

The next several years will likely determine whether gut-targeted therapies become a standard part of Alzheimer’s prevention and treatment or remain a promising but undelivered idea. GV-971’s approval in China has not yet been replicated in Western regulatory frameworks, and the drug’s mechanism of action through the microbiome is still debated. Larger fecal transplant trials are underway. Northwestern’s propionate research is moving toward more targeted interventions.

And the basic science connecting microbial metabolites to neuroinflammation grows more detailed with each passing year. What makes this field different from many Alzheimer’s dead ends of the past is that the gut is modifiable. You cannot change your APOE genotype or reverse decades of amyloid accumulation overnight, but you can change what you feed your gut bacteria starting today. The research is not yet strong enough to make specific clinical recommendations beyond well-established dietary guidelines, but it is strong enough to justify attention — both from the scientific community investing in large-scale trials and from individuals making daily choices about what they eat.

Conclusion

The connection between gut bacteria and Alzheimer’s disease is no longer speculative. Measurable shifts in the microbiome correlate with the earliest biomarkers of Alzheimer’s pathology, specific mechanisms like propionate’s suppression of neuroinflammation have been identified, and multiple clinical trials of probiotics, fecal transplants, and microbiome-targeted drugs have shown cognitive improvements in patients with Alzheimer’s and mild cognitive impairment. With 7.2 million Americans currently living with Alzheimer’s and a new case of dementia emerging every 3.2 seconds worldwide, the urgency to develop effective interventions through every viable pathway — including the gut — cannot be overstated.

For individuals and caregivers, the practical takeaway is grounded but real: a Mediterranean-style diet rich in fiber, polyphenols, and diverse plant foods supports the gut bacteria most associated with brain-protective metabolites. Probiotic supplementation may offer additional benefits, particularly multi-strain formulations, though the evidence base is still maturing. The most important thing is not to wait for a perfect gut-targeted Alzheimer’s drug to arrive — it is to recognize that the daily choices shaping your microbiome are already shaping your brain, and to make those choices with the best available evidence in mind.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can probiotics prevent Alzheimer’s disease?

There is no definitive proof yet that probiotics prevent Alzheimer’s. A 2025 umbrella review of randomized controlled trials found that multi-strain probiotics improved cognition and memory in Alzheimer’s and MCI patients, but results varied significantly across studies. Probiotics may be one helpful component of a broader prevention strategy, but they should not be treated as a standalone solution.

What is the gut-brain axis and how does it relate to dementia?

The gut-brain axis refers to the bidirectional communication network between your gastrointestinal tract and your central nervous system. Gut bacteria produce metabolites like short-chain fatty acids that influence immune responses, intestinal barrier integrity, and blood-brain barrier permeability. Disruptions in this system have been linked to neuroinflammation and the buildup of amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

Which foods are best for gut bacteria linked to brain health?

The Mediterranean diet has the strongest evidence base, with its emphasis on vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, olive oil, and fish. Foods rich in polyphenols — berries, dark chocolate, green tea — have shown benefits for gut barrier integrity in preclinical models. High-fiber foods are particularly important because they feed bacteria that produce propionate and butyrate, short-chain fatty acids associated with reduced brain inflammation.

Has any gut-targeted drug been approved for Alzheimer’s?

GV-971, or sodium oligomannate, was approved in China in 2019. Derived from marine algae, it works by reshaping gut microbiota and showed significant cognitive improvement sustained over a 36-week Phase 3 trial. It has not been approved by regulatory agencies outside China, and its mechanism remains under scientific discussion.

Can a stool test detect Alzheimer’s risk?

Research has shown that gut microbiome analysis can improve machine learning predictions of preclinical Alzheimer’s status, but this has only been demonstrated in small study populations. A stool-based Alzheimer’s screening test is not currently available for clinical use, though it represents a promising and less invasive alternative to current diagnostic methods like PET scans and spinal taps.

Is fecal microbiota transplantation being tested for Alzheimer’s?

Yes. Early-phase fecal microbiota transplantation trials reported cognitive improvements in 2025. FMT involves transferring gut bacteria from a healthy donor to a patient’s intestinal tract to restore microbial balance. Larger trials are needed before this approach could become a standard treatment, but initial results have been encouraging.