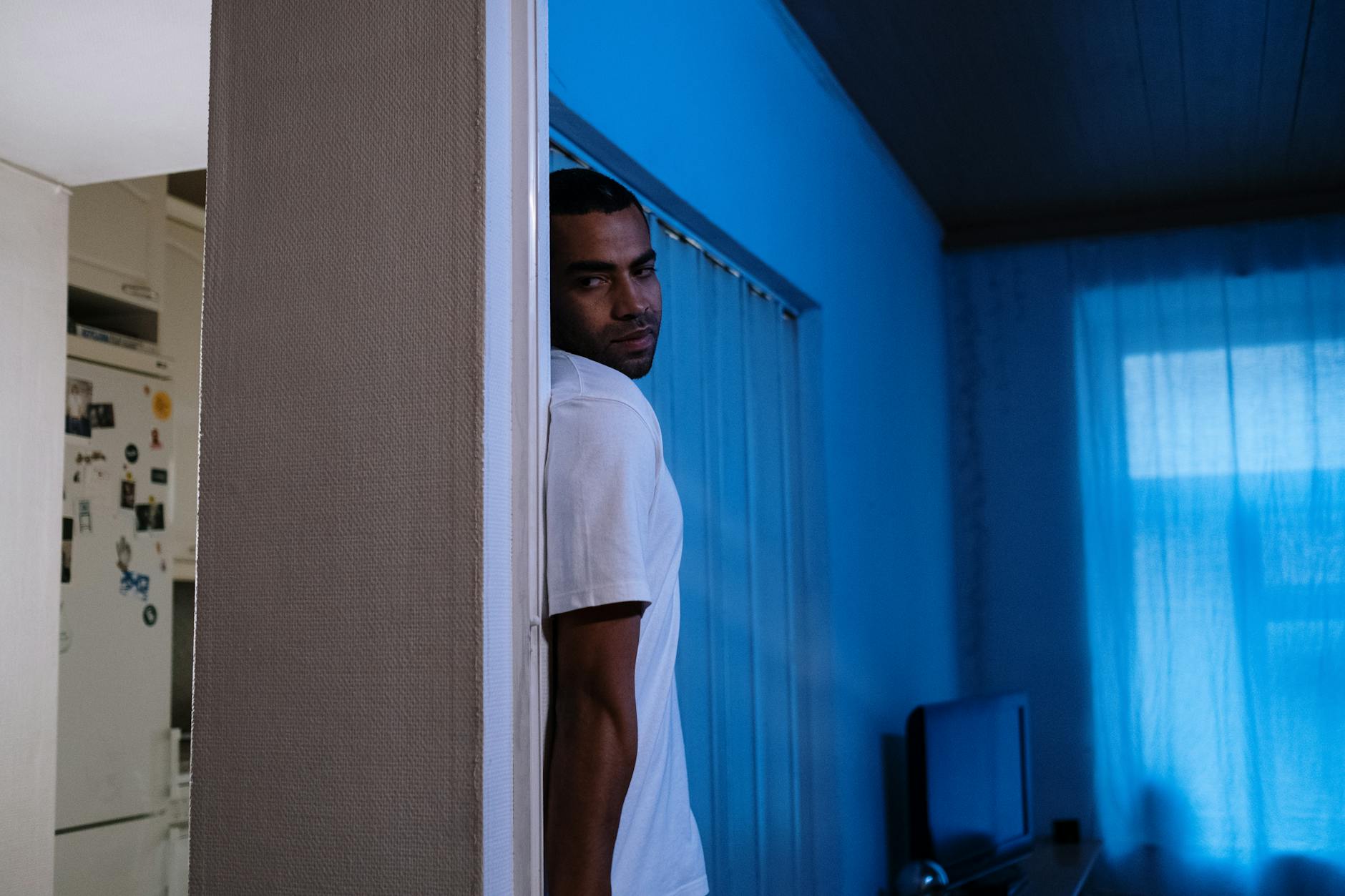

Paranoia in Alzheimer’s disease follows a rough but recognizable arc. It tends to surface as mild suspicion in the early stages, peak in intensity during the moderate middle stage, and persist — though sometimes less vocally — into late-stage disease. About 40 percent of people with Alzheimer’s will experience some form of psychosis over the course of the illness, with delusions far more common than hallucinations: 36 percent versus 18 percent, according to a review of 55 studies published in The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. Paranoid delusions specifically — the conviction that someone is stealing, spying, or conspiring — are the single most common type, affecting anywhere from 14.5 to 46 percent of patients depending on the study. Consider a common scenario: a woman with moderate Alzheimer’s places her wallet in a dresser drawer she rarely uses. Twenty minutes later, she cannot remember doing this.

Rather than accepting the gap in memory, her brain fills it with an explanation that feels more coherent to her — someone must have taken it. She accuses her daughter, who visits every afternoon. The accusation is specific, emotional, and genuinely believed. This is not manipulation or attention-seeking. It is paranoia driven by neurological damage, and it is one of the most distressing behavioral symptoms for both the person with Alzheimer’s and their family. This article breaks down how paranoia typically evolves across the stages of Alzheimer’s, what drives it at a neurological level, and what caregivers can actually do about it — from environmental adjustments to the limited pharmaceutical options now available, including the first FDA-approved medication for dementia-related agitation.

Table of Contents

- How Does Paranoia Progress Through the Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease?

- What Actually Causes Paranoia in Alzheimer’s — and When Memory Loss Is Not the Only Factor

- The Most Common Paranoid Delusions and What They Look Like in Daily Life

- Managing Paranoia Without Medication — What Works and What Doesn’t

- Medications for Alzheimer’s Paranoia — Limited Options with Serious Tradeoffs

- How Paranoia Differs from Other Alzheimer’s Behavioral Symptoms

- The Growing Scale of the Problem and What Lies Ahead

- Conclusion

How Does Paranoia Progress Through the Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease?

The trajectory of paranoia in Alzheimer’s is not perfectly linear, but research points to a general pattern. In the early stage, paranoia tends to show up as subtle suspicion rather than full-blown delusion. A person might repeatedly check locks, express vague worry that a neighbor is “watching,” or insist that small items keep disappearing. These behaviors are easy to dismiss or misattribute to normal aging anxiety, which is partly why early-stage paranoia often goes unrecognized. The person may still have enough cognitive function to mask or rationalize their suspicions, making it harder for family members to distinguish between reasonable concern and emerging delusion. The middle stage is where paranoia typically becomes unmistakable. Research from the Alzheimer’s Association indicates that psychotic symptoms are most active during the moderate stage of dementia. Delusions become more elaborate and more fixed. A husband might become convinced his wife of forty years is having an affair.

A mother might insist her adult children are conspiring to steal her house. These are not passing worries — they are deeply held beliefs that resist correction, and they can trigger aggressive behavior, refusal of care, or attempts to leave home. A pooled meta-analysis in Frontiers in Psychiatry found delusion prevalence of 31 percent across Alzheimer’s patients, with individual studies ranging as high as 73 percent in some populations. In the late stage, paranoia can remain persistent and overwhelming, but its expression often shifts. As cognitive and physical decline accelerates, the person may lose the verbal ability to articulate complex accusations or the physical capacity to act on them. This does not mean the fear has gone away — it may manifest as agitation, resistance to care, or visible distress without clear verbal explanation. The Alzheimer’s Society UK emphasizes an important caveat: paranoia can emerge at any stage, and dementia progression is unpredictable. Some people never develop paranoid symptoms at all. Others experience them early and intermittently throughout the disease.

What Actually Causes Paranoia in Alzheimer’s — and When Memory Loss Is Not the Only Factor

Memory loss is the primary engine of Alzheimer’s-related paranoia. When a person cannot remember placing their glasses on the kitchen counter, the missing glasses demand an explanation. A healthy brain shrugs and retraces its steps. A brain with significant hippocampal damage cannot retrace those steps — the memory was never consolidated. So the brain constructs a narrative: someone took them. This is not a choice. It is a cognitive system doing what cognitive systems do — seeking coherence — with broken tools. The National Institute on Aging describes paranoia in Alzheimer’s as the person’s way of making sense of a confusing world with declining cognition. However, memory loss alone does not fully explain why some patients develop severe paranoia while others with comparable cognitive decline do not.

changes in specific brain regions — particularly those involved in perception, reasoning, and threat assessment — play a significant role. Damage to the frontal lobes can impair the ability to evaluate whether a belief is plausible. Damage to temporal and parietal regions can distort how sensory information is processed, making familiar environments feel threatening. A longitudinal study found that over three years, 23 percent of Alzheimer’s patients developed only delusions, 9 percent developed only hallucinations, and 19 percent developed both — suggesting distinct but overlapping neurological pathways for different psychotic symptoms. Sensory impairment compounds the problem significantly. Poor vision or hearing can cause a person to misinterpret shadows, background noise, or partially heard conversations, fueling paranoid interpretation. Environmental factors matter too — unfamiliar settings, changes in routine, overstimulation, or even rearranging furniture can destabilize a person’s already fragile sense of orientation and safety. This means that not every episode of paranoia requires a pharmaceutical response. Sometimes the trigger is a new caregiver, a room that is too dark, or a television program the person cannot distinguish from reality.

The Most Common Paranoid Delusions and What They Look Like in Daily Life

Paranoid delusions in Alzheimer’s tend to cluster around a few recurring themes. The most common is theft — the belief that someone is stealing money, jewelry, or everyday items. This is directly linked to the memory-and-misplacement cycle described above, and it can target anyone from a spouse to a home health aide to a grandchild. In a household where a caregiver daughter manages her mother’s finances, accusations of theft can be devastating, especially when they are repeated to other family members or neighbors who may not understand the disease context. Persecutory delusions — the belief that someone is trying to cause harm — affect between 7 and 40 percent of patients. Delusions of spousal infidelity, reported in 1.1 to 26 percent of patients, are particularly painful for long-term partners. A man with moderate Alzheimer’s might see his wife speaking to a male neighbor and become convinced she is having an affair. He may bring it up repeatedly, become hostile, or refuse to be in the same room with her.

The belief is unshakeable not because the evidence is strong but because the neurological capacity to weigh evidence is damaged. Another common pattern involves believing that caregivers are imposters — a phenomenon sometimes overlapping with Capgras syndrome — or that the person is being watched or followed by police or strangers. What makes these delusions especially difficult for families is their specificity. They do not feel like confusion. They feel like accusations. A parent who says “you stole my ring” is not vaguely disoriented — they are making a direct, emotionally charged claim. The natural response is to defend yourself, produce evidence, or argue. But for the person with Alzheimer’s, the delusion is as real as any memory they still retain, and arguing only escalates distress. Understanding that these accusations originate in neurological damage — not in the relationship — is one of the hardest but most important shifts a caregiver can make.

Managing Paranoia Without Medication — What Works and What Doesn’t

Non-drug approaches are the recommended first-line treatment for paranoia in Alzheimer’s, according to both the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association. The core strategies are straightforward in concept but demanding in practice: do not argue with the delusion, provide calm reassurance, maintain predictable routines, and reduce environmental triggers that could fuel misinterpretation. If a parent insists someone stole their purse, the most effective response is often to say “that sounds upsetting — let me help you look for it” rather than “nobody stole anything.” The goal is to address the emotion, not the factual claim. Environmental modifications can make a meaningful difference. Ensuring adequate lighting reduces the shadows and visual ambiguity that can trigger paranoid interpretation. Keeping commonly misplaced items in consistent, visible locations reduces theft accusations.

Regular vision and hearing tests are essential — sensory impairment is a modifiable contributor to paranoia, and correcting it will not cure delusions but can reduce their frequency. Maintaining a stable daily routine minimizes the disorientation that fuels suspicion. These interventions have a real tradeoff, though: they require enormous consistency and patience from caregivers who are often exhausted, grieving, and managing the paranoia alongside dozens of other disease symptoms. The limitation of non-drug approaches is that they do not always work, particularly in moderate-to-severe cases where delusions are fixed and agitation is high. A person who is convinced their caregiver is poisoning their food may refuse to eat. Someone who believes strangers are breaking into the house at night may try to leave. When paranoia creates safety risks or makes basic care impossible, medication becomes a necessary conversation — not a failure of caregiving, but a recognition that behavioral strategies have a ceiling.

Medications for Alzheimer’s Paranoia — Limited Options with Serious Tradeoffs

The pharmaceutical landscape for treating paranoia in Alzheimer’s is narrow and comes with significant caveats. Cholinesterase inhibitors — including donepezil (Aricept) and galantamine (Razadyne) — which are primarily prescribed to slow cognitive decline, have been shown in some cases to decrease paranoia and delusions as a secondary benefit. These are not anti-psychotics; they work by boosting acetylcholine levels in the brain, and their effect on paranoia is modest and inconsistent. But because many Alzheimer’s patients are already taking them, any reduction in psychotic symptoms is a welcome bonus. On May 10, 2023, the FDA approved brexpiprazole (Rexulti) as the first and only medication specifically indicated for agitation associated with dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. In clinical trials, Rexulti achieved a 31 percent greater reduction in agitation symptoms compared to placebo. This approval was significant because, prior to it, no medication had FDA approval for any behavioral symptom of Alzheimer’s — physicians were prescribing antipsychotics off-label, often with limited evidence and considerable risk.

However, Rexulti carries a Boxed Warning — the FDA’s most serious — regarding increased risk of death in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis. This is the same black box warning that applies to all antipsychotics used in this population. The tradeoff is stark. Untreated severe paranoia can lead to aggression, self-harm, caregiver burnout, and premature institutionalization. But the medications available carry real risks, including sedation, falls, stroke, and increased mortality. Families and clinicians have to weigh these risks against the severity of symptoms, and there is no formula that makes the decision easy. The current clinical consensus — start with non-drug interventions, escalate to medication only when necessary, use the lowest effective dose, and reassess regularly — reflects this tension rather than resolving it.

How Paranoia Differs from Other Alzheimer’s Behavioral Symptoms

Paranoia is sometimes conflated with general confusion or sundowning, but it is a distinct phenomenon with different implications for care. A person experiencing sundowning may become agitated, restless, or disoriented in the late afternoon and evening — but they are not necessarily holding a specific false belief about another person’s intentions. Paranoia involves a targeted accusation or conviction: someone is stealing, someone is lying, someone is dangerous. This specificity is what makes it so interpersonally destructive and so difficult for families to absorb without taking it personally. It also differs from hallucinations, though the two can coexist.

A hallucination is a sensory experience — seeing a person who is not there, hearing voices. A delusion is a fixed false belief. A patient who sees a stranger in the living room is hallucinating. A patient who believes their son is plotting to put them in a nursing home — with no sensory distortion involved — is delusional. The distinction matters for treatment because hallucinations sometimes respond to environmental changes (better lighting, removing mirrors) while delusions tend to be more resistant and more closely tied to the underlying cognitive decline. The three-year longitudinal data showing separate incidence rates — 23 percent delusions only, 9 percent hallucinations only, 19 percent both — reinforces that these are related but separable symptoms.

The Growing Scale of the Problem and What Lies Ahead

The numbers make the urgency clear. An estimated 7.2 million Americans age 65 and older currently live with Alzheimer’s dementia, a figure projected to reach 13.8 million by 2060 according to the 2025 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report. Prevalence climbs sharply with age: 5 percent of those aged 65 to 74, 13.2 percent of those 75 to 84, and 33.4 percent of those 85 and older. If roughly a third of these individuals will experience paranoid delusions at some point during their illness, the number of families confronting this specific symptom will grow into the millions in the coming decades.

Research into dementia-related psychosis is expanding but still underfunded relative to the scale of the problem. The approval of Rexulti in 2023 opened a door, but one medication with a black box warning is not a solution — it is a starting point. More targeted therapies, better biomarkers for predicting who will develop psychotic symptoms, and stronger caregiver support infrastructure are all needed. For now, the most important thing families can do is understand that paranoia in Alzheimer’s is a neurological symptom, not a reflection of the relationship, and that its appearance — while distressing — is a known and expected part of the disease for a significant minority of patients.

Conclusion

Paranoia in Alzheimer’s typically follows a pattern: emerging as subtle suspicion in the early stage, intensifying into fixed, accusatory delusions during the moderate stage, and persisting — though sometimes less articulately — into late-stage disease. It affects roughly a third of all Alzheimer’s patients and is driven primarily by memory loss, brain changes, sensory impairment, and environmental disorientation. The most common manifestations — accusations of theft, infidelity, and conspiracy — are deeply painful for families, but they originate in neurological damage rather than interpersonal reality.

Management starts with non-drug strategies: validating emotions without reinforcing delusions, maintaining routine, correcting sensory deficits, and reducing environmental triggers. When these are insufficient, medications including cholinesterase inhibitors and, since 2023, brexpiprazole offer some relief but carry meaningful risks. There is no clean answer here, only a continuum of tradeoffs that families and clinicians navigate together. Understanding the stage-by-stage trajectory of paranoia does not eliminate its impact, but it does provide a framework — something to hold onto when a loved one looks at you with genuine fear and says something that is not true.