Falls, burns, poisoning, and wandering represent the most frequent causes of injury among people living with dementia in home settings. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, more than six million Americans currently live with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia, and the majority remain in their own homes throughout much of the disease course. Research published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society indicates that people with dementia are two to three times more likely to experience a fall compared to cognitively intact older adults, and those falls are more likely to result in serious injury, including hip fractures and traumatic brain injury. Creating a safe home environment is not optional — it is a clinical and ethical imperative for every caregiver and family. This guide is designed to serve as the single most comprehensive resource on home safety and environmental modifications for dementia care.

Whether you are a family caregiver adjusting a longtime family home, a professional caregiver managing a client’s living space, or a healthcare provider advising families on best practices, you will find detailed, evidence-based guidance here. We cover every major area of the home — from bathrooms and kitchens to bedrooms, outdoor spaces, and transitional zones — with specific strategies grounded in occupational therapy research, geriatric safety literature, and the lived experience of dementia care professionals. For a broader overview of foundational principles, see How to Create a Safe Home Environment for Dementia Patients. The philosophy underlying effective home modification for dementia is straightforward but often misunderstood. The goal is not to create a sterile, institutional space.

Rather, it is to preserve familiarity, autonomy, and dignity while systematically removing hazards that a person with impaired judgment, spatial awareness, and memory can no longer reliably navigate. A well-modified home reduces caregiver burden, decreases emergency room visits, and — critically — allows the person with dementia to maintain function and confidence longer. Studies from the University of Stirling’s Dementia Services Development Centre have demonstrated that thoughtful environmental design can reduce agitation by up to 30 percent and significantly decrease the use of psychotropic medications. Throughout this guide, we will reference specific articles and resources available on this site that explore individual topics in greater depth. Taken together, these resources provide a layered system of knowledge: this pillar page gives you the strategic framework, while linked articles offer tactical detail on subjects such as bathroom grab bars, bedroom lighting, and sleep environment optimization.

For those beginning the process of long-term home planning, How to create a safe home environment for aging in place provides essential context for thinking beyond immediate safety to sustained livability.

What This Guide Covers

- Assessing Your Home for Dementia Safety Risks

- Bathroom Safety: Preventing Falls and Confusion

- Kitchen Safety and Meal Preparation Modifications

- Lighting Changes That Reduce Confusion

- Bedroom and Sleep Environment Setup

- Removing Clutter and Reducing Overstimulation

- Door and Window Safety Measures

- Outdoor Spaces and Garden Safety

- Signage, Color Coding, and Wayfinding Aids

- Adapting the Home as the Disease Progresses

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

Assessing Your Home for Dementia Safety Risks

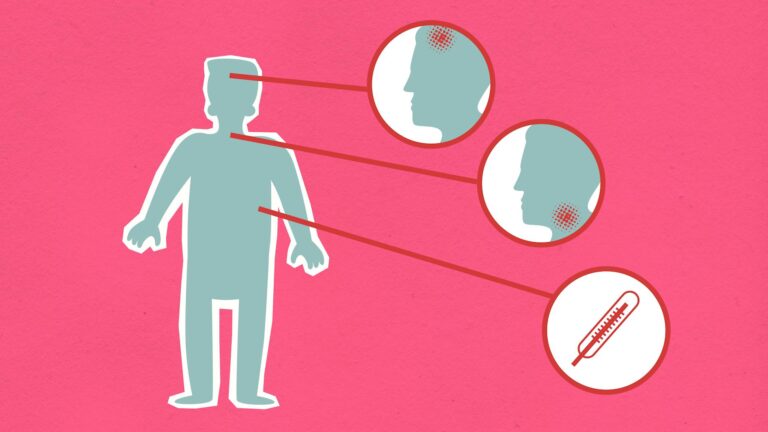

Before making any modification, a structured home safety assessment provides the necessary baseline. Occupational therapists recommend a room-by-room walkthrough that evaluates five core risk domains: fall hazards, fire and burn risks, poisoning and ingestion risks, wandering and elopement potential, and sources of confusion or agitation. The assessment should be conducted with the person with dementia present whenever possible, because observing how they actually move through and interact with the space reveals risks that a checklist alone cannot capture. Watch where they hesitate, what they reach for, where they seem disoriented, and what surfaces they rely on for balance. Begin at the front entrance and move systematically through every room. In each space, get low and look at the environment from the perspective of someone who may be unsteady on their feet, who may not reliably distinguish between similar objects, and whose depth perception may be impaired.

Floor surfaces deserve particular scrutiny. Loose rugs, abrupt transitions between flooring types, glossy or highly reflective surfaces, and dark thresholds that might be perceived as holes or steps all present fall risks. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that one in four Americans aged 65 and older falls each year, and for those with cognitive impairment, the risk is amplified by impaired judgment about their own physical abilities. Document everything during the assessment. Photograph problem areas, note the locations of electrical outlets, chemical storage, sharp objects, and potential climb points. Identify where the person with dementia spends most of their time and trace their most common movement paths — to the bathroom, to the kitchen, to the front door.

These high-traffic corridors should receive the highest priority for modification. Check that smoke detectors and carbon monoxide detectors are functional, that fire extinguishers are accessible, and that emergency exit routes are clear. It is important to repeat this assessment periodically. Dementia is progressive, and the modifications that were sufficient six months ago may no longer address current risks. Many occupational therapy departments offer formal home safety assessments, and some Area Agencies on Aging provide this service at no cost. For families managing the process independently, the approach described in How to Create a Safe Home Environment for Dementia Patients offers a practical framework.

The investment of a few hours in a thorough initial assessment can prevent injuries that carry life-altering consequences.

Bathroom Safety: Preventing Falls and Confusion

The bathroom is consistently identified as the most dangerous room in the home for people living with dementia. Wet, hard surfaces combine with complex sequencing tasks — undressing, transferring to a toilet or shower, managing water temperature, and maintaining balance — to create a high-risk environment. The National Institute on Aging notes that bathroom falls account for a disproportionate share of injuries among older adults, and for people with dementia, the added challenges of apraxia, spatial disorientation, and difficulty interpreting sensory cues magnify every risk. Grab bars are the single most impactful structural modification in the bathroom. They should be installed next to the toilet, inside the shower or tub, and at the entrance to the bathing area. Bars must be anchored into wall studs or reinforced with appropriate backing — suction-cup models are not adequate for weight-bearing use. A detailed guide to proper installation and placement is available in Alzheimer’s Bathroom Safety: Installing grab bars.

Beyond grab bars, consider a walk-in shower with a zero-threshold entry, a shower bench or transfer seat, and a handheld showerhead that allows the caregiver or the individual to direct water flow precisely. Toilet access presents its own set of challenges. Raised toilet seats reduce the distance and effort required to sit and stand, and toilet frames with armrests provide additional stability. For individuals in later stages, simplified access becomes critical. The article Alzheimer’s and Toilet Access: Creating Safe Bathroom Environments addresses the full spectrum of toilet-related modifications. Caregivers should also be aware of behavioral issues such as incontinence product disposal. Flushing of inappropriate items can cause significant plumbing problems, and strategies for managing this are detailed in Dementia and Bathroom Safety: Stopping Patients from Clogging Toilets with Diapers.

Water temperature must be controlled to prevent scalding. Set the household water heater to 120 degrees Fahrenheit or below, and consider installing anti-scald valves on faucets and showerheads. Remove or lock away medications, razors, cleaning products, and any other potentially harmful items. Use non-slip mats both inside the tub or shower and on the bathroom floor, and ensure the bath mat has a rubber backing that stays firmly in place. Nighttime bathroom trips represent a particularly high-risk period. Motion-activated lighting can bridge the gap between a dark hallway and a fully lit bathroom without the disorientation of sudden bright light. For evidence-based approaches to this problem, see Can Motion Lights Improve Night Time Bathroom Safety.

Kitchen Safety and Meal Preparation Modifications

The kitchen poses risks related to fire, burns, sharp objects, toxic substances, and the operation of complex appliances. For people with dementia, the progressive loss of executive function means that multi-step tasks like cooking — which require sequencing, timing, and sustained attention — become increasingly dangerous. A study in the British Journal of Occupational Therapy found that kitchen-related accidents are among the top three causes of injury for community-dwelling people with dementia. Start with the stove, which represents the most serious fire risk. Automatic stove shut-off devices are available and can be installed on gas or electric ranges. These devices use motion sensors or timers to cut power to the stove when it has been left unattended.

If an automatic device is not feasible, consider removing stove knobs when the kitchen is not in active supervised use or installing knob covers. Keep a fire extinguisher accessible and ensure the caregiver knows how to use it. Replace any dish towels, pot holders, or curtains near the stove that are frayed or heat-damaged. Secure all cleaning products, chemicals, and potentially toxic substances in a locked cabinet. People with dementia may not distinguish between a bottle of juice and a bottle of cleaning solution, particularly as the disease progresses and reading comprehension deteriorates. Sharp knives should be stored in a locked drawer or replaced with safer alternatives for supervised meal preparation.

Appliances that pose burn or injury risk — toasters, blenders, food processors — should be unplugged when not in supervised use and, if necessary, stored out of sight. Simplify the kitchen environment so that items the person uses daily are easily visible and accessible while hazards are minimized. Meal preparation can be maintained as a meaningful activity for as long as safely possible by adapting the tasks involved. A person who can no longer safely operate a stove may still be able to wash vegetables, tear lettuce, stir cold ingredients, or set the table. These contributions preserve dignity and a sense of purpose. Use plates and cups that contrast in color with the table surface to help the person with dementia identify their place setting.

For guidance on reducing mealtime agitation and sensory overload, see How do I adjust the dining environment to reduce overstimulation for my loved one?. Consider installing childproof locks on the refrigerator and oven if the person is prone to unsupervised access during the night.

Lighting Changes That Reduce Confusion

Lighting is one of the most underappreciated factors in dementia home safety, yet research consistently identifies it as one of the most impactful. The aging eye admits roughly one-third less light than a younger eye, and dementia compounds this with impaired visual processing. Shadows, glare, dim corridors, and abrupt transitions between bright and dark areas can trigger confusion, anxiety, visual hallucinations, and falls. A landmark study by researchers at the Lighting Research Center at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute demonstrated that exposure to appropriate lighting patterns improved sleep quality, reduced agitation, and decreased depressive symptoms in people with Alzheimer’s disease. The foundational principle is uniform, diffused, non-glare lighting throughout the home. Eliminate sharp contrasts between rooms: if the kitchen is brightly lit and the adjacent hallway is dim, the transition itself becomes a hazard.

Use frosted bulbs or lamp shades that prevent direct glare. Increase the overall illumination level in the home — the Illuminating Engineering Society recommends that living spaces for older adults be lit to approximately twice the level recommended for younger adults. Pay particular attention to task areas such as kitchen counters, reading spaces, and bathroom vanities, where focused but non-glare lighting is essential. Nighttime lighting deserves special consideration because sundowning — the increase in confusion and agitation that many people with dementia experience in the late afternoon and evening — is closely linked to diminishing light levels. Nightlights in bedrooms, hallways, and bathrooms provide orientation and reduce the disorientation of waking in complete darkness. For an exploration of why this matters, see Why are nightlights important in senior bedrooms and bathrooms?.

Motion-activated lights in hallways and near the bed provide illumination exactly when and where it is needed without requiring the person to find and operate a switch. Additional guidance on bedroom-specific lighting can be found in What are safe lighting tips for senior bedrooms to prevent injuries?. During the day, maximize natural light exposure. Open blinds and curtains in the morning, position seating areas near windows, and consider light therapy lamps for individuals who spend significant time indoors. Circadian lighting systems, which adjust color temperature and brightness to mirror the natural arc of daylight, are increasingly available for residential use and show promise in supporting sleep-wake cycles. The connection between environmental light and cognitive function is further explored in How a Simple Change in Your Sleep Environment Can Enhance Brain Function.

Bedroom and Sleep Environment Setup

Sleep disturbance affects up to 70 percent of people with dementia at some point during the disease course, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. Poor sleep accelerates cognitive decline, increases fall risk during nighttime wandering, and contributes to caregiver exhaustion. The bedroom environment plays a decisive role in sleep quality and safety, and modifications here deliver benefits that ripple outward into every other aspect of daily function. The bed itself should be evaluated for both safety and accessibility. A bed that is too high increases fall risk when getting in and out; a bed that is too low makes standing difficult. Adjustable-height beds or bed risers can calibrate the height so that the person’s feet rest flat on the floor when seated on the edge. Bed rails remain controversial — they prevent rolling out of bed but can also cause entrapment injuries, and their use should be discussed with a healthcare provider.

For individuals at risk of falling out of bed, a low-profile bed combined with a padded floor mat alongside the bed may be safer than rails. The broader sleep environment should promote calm, quiet, and sensory consistency. The bedroom should be reserved for sleep and rest — not television, not storage, not activity. Keep the room cool, dark during sleep hours, and free from distracting noise. Blackout curtains or shades can block streetlight or early morning sun that disrupts sleep. For comprehensive guidance, see How to Build a Healthy Sleep Environment and Alzheimer’s Bedroom Environment: Creating a calm, quiet space. Address nighttime confusion specifically.

A familiar room layout, a visible clock with large analog or digital display, and a photograph or personal item on the nightstand all provide orienting cues when the person wakes during the night. Avoid rearranging bedroom furniture, as spatial memory for well-established layouts can persist even when other memory systems fail. The article How can I adjust the bedroom environment to reduce nighttime confusion for my loved one? provides further strategies. Caregivers seeking to make the bedroom both safe and predictable will find additional recommendations in How can I create a safe and predictable environment in my patient’s bedroom?. Multi-sensory approaches are gaining attention in dementia sleep research. The use of lavender aromatherapy, white noise machines, and weighted blankets has shown modest but consistent benefits in small clinical trials. These interventions work best when they become part of a consistent bedtime routine rather than being introduced sporadically.

For an in-depth look at this emerging area, see Creating multi-sensory sleep environments for dementia.

Removing Clutter and Reducing Overstimulation

The relationship between environmental complexity and behavioral symptoms in dementia is well established. Research from the Bradford Dementia Group and others has shown that cluttered, visually noisy environments increase agitation, confusion, and the frequency of catastrophic reactions. For a person with dementia, the brain’s ability to filter irrelevant stimuli is progressively impaired, meaning that every object in the visual field competes for processing resources that are already severely limited. Begin decluttering by identifying the items the person uses daily and making those prominent and accessible. Everything else should be stored out of sight. This applies to countertops, tabletops, shelves, and open storage areas.

Remove decorative objects that could be mistaken for functional items — a decorative bowl of stones on a coffee table may be perceived as food. Remove or cover mirrors if they cause distress, as some people with dementia do not recognize their own reflection and may perceive a stranger in the room. Reduce the number of patterns in the environment: busy wallpaper, patterned carpets, and striped upholstery can create visual confusion and even trigger hallucinations. Auditory clutter is equally important. Background television, multiple simultaneous conversations, appliance noise, and outdoor sounds all contribute to an overwhelming sensory environment. Limit background noise during waking hours.

If the person with dementia enjoys music, play familiar songs at a moderate volume rather than leaving a television running on unfamiliar programming. For guidance on managing sensory input during mealtimes specifically, refer to How do I adjust the dining environment to reduce overstimulation for my loved one?. Similarly, distractions in the sleep environment should be minimized — see How can I ensure that my loved one’s sleep environment is free from distractions?. A simplified environment does not have to feel sparse or institutional. Personal photographs, a favorite chair, a meaningful quilt, and a small number of cherished objects provide warmth and familiarity. The key is intentionality — every item in the environment should serve a clear purpose, whether functional or emotional.

When the environment is simplified, the person with dementia expends less cognitive effort on processing their surroundings and has more capacity available for engagement, communication, and enjoyment.

Door and Window Safety Measures

Wandering is one of the most dangerous behaviors associated with dementia. The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that six in ten people with dementia will wander at some point, and if not found within 24 hours, up to half of those who wander may suffer serious injury or death. Securing doors and windows is therefore among the most urgent home modifications a caregiver can make. Standard door locks are often inadequate because many people with dementia retain the procedural memory for operating familiar lock mechanisms long after other cognitive abilities have declined. Double-keyed deadbolts, which require a key on both sides, prevent exit but also pose a fire safety risk if the key is not immediately accessible in an emergency.

A safer approach is to install locks or latches in non-standard positions — high on the door or at the base — where the person with dementia is unlikely to look. Door alarms that sound when an exterior door is opened provide an additional layer of protection. Chime-style alerts allow the caregiver to monitor door activity without the harsh sound of a traditional alarm. Windows require attention as well, particularly on upper floors. Window locks or stops that limit how far a window can open prevent falls while still allowing ventilation.

Sliding glass doors should be secured with a bar or pin in the track. Consider placing a dark mat or applying a dark color strip on the floor in front of exits — some people with dementia perceive dark floor areas as holes or steps and will avoid crossing them, though this technique should be used cautiously and its effect monitored. Camouflage strategies can supplement physical security. Painting the door the same color as the surrounding wall, covering the door handle with a cloth that matches the door color, or hanging a curtain over the door can reduce the visual salience of the exit. These approaches exploit the visual processing changes associated with dementia rather than relying solely on physical barriers.

However, no single strategy is fail-safe, and a layered approach combining physical locks, alarms, visual camouflage, and caregiver vigilance provides the best protection. GPS tracking devices worn as wristbands or clipped to clothing offer a last line of defense if the person does leave the home undetected.

Outdoor Spaces and Garden Safety

Access to outdoor space provides significant benefits for people with dementia, including reduced agitation, improved mood, better sleep, and increased physical activity. A study published in the International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry found that regular access to gardens and outdoor areas was associated with lower levels of cortisol and fewer incidents of aggressive behavior. The goal is not to eliminate outdoor access but to make it safe. A secure perimeter is the first priority. Fences should be high enough to prevent climbing — a minimum of five feet is generally recommended — and gates should have locks that are not easily operated by someone with impaired cognition. Inspect the perimeter regularly for gaps, weak points, or areas where the person could squeeze through.

Hedges and dense plantings along the fence line can serve as both a visual screen that reduces the impulse to exit and a physical barrier that supplements the fence. Within the outdoor space, remove or secure hazards. Toxic plants — including common garden varieties such as foxglove, oleander, lily of the valley, and certain mushrooms — should be removed entirely. Garden chemicals, fertilizers, insecticides, and sharp tools should be stored in a locked shed. Swimming pools, ponds, or water features must be fenced or covered, as drowning risk is significantly elevated for people with dementia. Pathways should be smooth, level, and clearly defined.

Avoid gravel or loose stone surfaces that create trip hazards, and ensure that path edges are visually distinct from surrounding ground. Create an inviting outdoor environment that encourages safe engagement. Raised garden beds allow participation in gardening without the need to bend or kneel. Comfortable, stable seating with armrests encourages rest and enjoyment. Shade structures protect against sun exposure and overheating, which can exacerbate confusion. A circular or looping path design allows the person to walk without reaching a dead end, which can trigger frustration or anxiety.

The outdoor space should be visible from inside the home so that the caregiver can monitor activity without constant direct supervision.

Signage, Color Coding, and Wayfinding Aids

As dementia progresses, the ability to navigate even a familiar environment deteriorates. Wayfinding aids — visual cues that help a person identify where they are, where they need to go, and what a space or object is for — can substantially extend independent function and reduce episodes of confusion and distress. These aids leverage the brain’s preserved capacity for processing visual information, color, and simple symbols even when verbal and spatial memory have declined. Signage should be simple, high-contrast, and positioned at eye level. Labels on doors — “Bathroom,” “Bedroom,” “Kitchen” — using large black text on a white or yellow background help with room identification. Adding a relevant picture or symbol alongside the word (a toilet icon on the bathroom door, for example) increases comprehension as reading ability declines.

Avoid signs that rely on abstract symbols or color alone, as interpretive capacity varies and can change as the disease progresses. Signs should be affixed consistently in the same location on every door so the person learns to look for them in a predictable spot. Color coding is a powerful complementary strategy. Painting the bathroom door a distinctive color — different from all other doors — creates a persistent visual cue that can support toileting independence long into the disease course. Using a contrasting toilet seat color (for example, a dark seat on a white toilet) helps the person identify the toilet and orient themselves correctly. Similarly, contrasting plate colors against the table surface help with mealtime independence.

Research from the University of Stirling found that red plates and cups increased food and fluid intake in people with dementia by up to 25 percent compared to white dishware on a white table. Floor-level wayfinding can guide movement through the home. A strip of colored tape along the floor from the bedroom to the bathroom creates a visual path to follow during nighttime trips. Contrasting floor and wall colors at transitions help define room boundaries. Avoid highly reflective or polished floor surfaces, which can be perceived as wet and trigger fear or avoidance. Consistently applied visual cues create an environment that speaks to the person with dementia without requiring verbal instruction, reducing dependence on caregiver reminders and preserving a measure of autonomy.

Adapting the Home as the Disease Progresses

Dementia is not static, and neither should the home environment be. The modifications appropriate in the early stages — when the person may need only reminders, simplified routines, and basic safety measures — differ substantially from those required in the middle and late stages, when physical dependence increases and behavioral symptoms may intensify. Caregivers who understand this trajectory can plan ahead, implementing changes incrementally rather than in crisis. In the early stage, the emphasis is on maintaining independence while removing the most serious hazards. This may involve securing medications, removing or disabling dangerous appliances, installing grab bars in the bathroom, and improving lighting. The person may still be able to participate in decisions about their environment, and this participation should be encouraged.

Involving the person in choosing new nightlights, selecting paint colors for wayfinding, or rearranging furniture for safety helps preserve agency and reduces resistance to change. For advice on supporting a loved one through these transitions, see How do I help my loved one adjust to changes in our home that affect their sleep environment?. In the middle stage, physical safety becomes more complex. The person may have difficulty with stairs, may wander at night, may not recognize familiar rooms, and may become agitated by environmental stimuli they previously tolerated. This is the stage where door alarms, bed sensors, motion-activated lighting, and more comprehensive bathroom modifications typically become necessary. Moving the primary living space to a single floor — ideally with the bedroom, bathroom, and living area in close proximity — reduces the number of transitions the person must navigate.

The bedroom environment requires particular attention at this stage; guidance is available in How do I ensure the bedroom is a safe environment for my loved one at night?. In the late stage, the person may be largely bedbound or chair-bound, and the environment must support total care. Hospital-style beds, pressure-relieving mattresses, patient lifts, and incontinence management systems become central features of the home. The risk of skin breakdown, aspiration, and contracture replaces the earlier risks of wandering and kitchen accidents. Even in this stage, the environment matters: natural light, familiar sounds, and the presence of personal objects continue to provide comfort and connection. The quality of the sleep environment remains critical throughout all stages, as explored in How Does Your Sleep Environment Affect the Quality of Your Rest? and How a Simple Change in Your Sleep Environment Can Boost Brain Function.

Conclusion

Modifying the home environment for dementia care is one of the most consequential actions a caregiver can take. The evidence is clear: a thoughtfully adapted home reduces falls, decreases behavioral symptoms, extends independent function, delays institutional placement, and improves quality of life for both the person with dementia and their caregiver. The modifications described in this guide — from grab bars and stove shut-off devices to color-coded doors and circadian lighting — are not luxuries. They are clinical interventions that address the specific functional and cognitive deficits that dementia produces.

The process need not be overwhelming. Begin with a structured assessment, prioritize the highest-risk areas (typically the bathroom, kitchen, and exit points), and implement changes incrementally. Revisit the home environment every few months as the disease progresses, adjusting modifications to match the person’s current abilities and needs. Engage occupational therapists, geriatric care managers, and dementia care specialists when possible — their expertise can identify risks and solutions that even the most attentive family caregiver might overlook.

Above all, remember that the goal is not merely to prevent harm but to create a space where the person with dementia can live with the greatest possible comfort, dignity, and engagement. A safe home is not one stripped of all personality and warmth. It is one where hazards have been thoughtfully addressed so that the person can focus their remaining capacities on connection, enjoyment, and the activities that give their days meaning. Every modification you make is an act of care that speaks louder than words.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the single most important home safety modification for someone with dementia?

While needs vary by individual and disease stage, installing grab bars in the bathroom and ensuring adequate lighting throughout the home are consistently identified by occupational therapists as the two highest-impact modifications. Bathroom falls are the leading cause of injury-related hospitalization for people with dementia living at home, making this room the priority starting point.

How much does it cost to modify a home for dementia safety?

Costs vary widely depending on the scope of modifications. Basic changes such as installing grab bars, adding nightlights, removing rugs, and securing cabinets can often be accomplished for a few hundred dollars. More extensive modifications such as walk-in showers, stove shut-off devices, and security systems may cost several thousand dollars. Medicare does not typically cover home modifications, but some Medicaid waiver programs, Veterans Affairs programs, and nonprofit organizations offer financial assistance.

When should I start making home modifications?

As early as possible after diagnosis. Many modifications, such as improved lighting and clutter reduction, benefit the person immediately and are easier to adjust to when cognitive function is still relatively preserved. Planning ahead also allows you to implement changes gradually rather than making sweeping alterations during a crisis, which can be more disorienting for the person with dementia.

Should I remove all mirrors from the home?

Not necessarily. Mirror removal is appropriate only if the person with dementia shows signs of distress when encountering their reflection — for example, speaking to the mirror as if it were a stranger or becoming agitated. If mirrors do not cause distress, they can be left in place. Monitor the person’s response over time, as reactions to mirrors may change as the disease progresses.

How can I prevent my loved one from wandering out of the house at night?

A layered approach is most effective. Install door alarms or chimes on all exterior doors. Place locks in non-standard positions where the person is unlikely to look. Use motion-sensor lights in hallways to gently illuminate nighttime movement. Ensure the bedroom environment supports continuous sleep to reduce the frequency of nighttime waking. Consider a GPS tracking device as a safety net. For more on nighttime bedroom safety, see How do I ensure the bedroom is a safe environment for my loved one at night?.

Is it safe to let someone with dementia use the kitchen?

With appropriate supervision and modifications, many people with early to moderate dementia can continue to participate in kitchen activities. The key is to match the task to the person’s current abilities. Simple tasks like washing produce, stirring ingredients, or setting the table can be done safely. Stove use should be supervised, and automatic shut-off devices provide an additional safety layer. Remove access to sharp knives and toxic substances.

How do I make the home safer without making it feel like an institution?

Focus on modifications that are subtle and integrated into the existing decor. Choose grab bars in finishes that complement the bathroom design. Use furniture-style locks rather than industrial hardware. Maintain personal photographs, familiar objects, and the person’s preferred color palette. The most effective modifications are often invisible to visitors — improved lighting, secured cabinets, removed trip hazards — while the environment retains its warmth and personality.

What lighting is best for someone with dementia?

Uniform, non-glare, warm-toned lighting is ideal during the day, with brightness levels roughly double what would be standard for a younger adult. At night, low-level amber or warm-white nightlights in bedrooms, hallways, and bathrooms provide orientation without disrupting sleep. Maximize natural daylight exposure during the day to support circadian rhythms. Avoid fluorescent lighting, which can flicker and cause agitation.

How often should I reassess the home environment?

A formal reassessment every three to six months is a reasonable schedule, though any significant change in the person’s behavior or function should prompt an immediate review. If the person experiences a fall, begins wandering, shows new agitation patterns, or loses a previously retained skill, the environment should be evaluated for modifications that address the new risk.

Can technology help with home safety for dementia?

Yes. Motion sensors, door and window alarms, automatic stove shut-off devices, medication dispensers with alarms, GPS tracking devices, video monitoring systems, and smart home platforms that allow remote control of lights and locks all have roles to play. Technology works best as a supplement to — not a replacement for — structural modifications and caregiver presence. Start with the simplest effective solution and add complexity only as needed.

Explore More on This Topic

- Why are nightlights important in senior bedrooms and bathrooms?

- Practice good sleep hygiene by creating a comfortable and relaxing sleep environment.

- How to Create a Relaxing Sleep Environment

- How to Build a Healthy Sleep Environment

- How sleep environments affect memory-related dreams

- How do I help my loved one adjust to changes in our home that affect their sleep environment?

- How can I ensure that my loved one’s sleep environment is free from distractions?

- How a Simple Change in Your Sleep Environment Can Enhance Brain Function

- How a Simple Change in Your Sleep Environment Can Boost Brain Function

- How Does Your Sleep Environment Affect the Quality of Your Rest?

- Creating multi-sensory sleep environments for dementia

- Alzheimer’s Bathroom Safety: Installing grab bars

- How do I adjust the dining environment to reduce overstimulation for my loved one?

- Dementia and Bathroom Safety: Stopping Patients from Clogging Toilets with Diapers

- Can Motion Lights Improve Night Time Bathroom Safety

- What are safe lighting tips for senior bedrooms to prevent injuries?

- What Are the Best Bedroom Environments for Supporting Brain Health?

- How do I ensure the bedroom is a safe environment for my loved one at night?

- How can I create a safe and predictable environment in my patient’s bedroom?

- How can I adjust the bedroom environment to reduce nighttime confusion for my loved one?

- Creating the Perfect Menopausal Bedroom Environment

- Alzheimer’s and Toilet Access: Creating Safe Bathroom Environments

- Alzheimer’s Bedroom Environment: Creating a calm, quiet space

- How to create a safe home environment for aging in place

- How to Create a Safe Home Environment for Dementia Patients