Understanding what’s the best music playlist setup for dementia therapy? is essential for anyone interested in dementia care and brain health. This comprehensive guide covers everything you need to know, from basic concepts to advanced strategies. By the end of this article, you’ll have the knowledge to make informed decisions and take effective action.

Table of Contents

- How Many Songs Should a Dementia Music Therapy Playlist Include?

- Why You Need Two Different Playlist Types

- The Gerdner Protocol: Timing Music for Maximum Impact

- Headphones Versus Speakers: Choosing the Right Delivery Method

- Common Mistakes That Undermine Music Therapy Effectiveness

- Building a Playlist Through Life Story Investigation

- The Measurable Benefits and Realistic Expectations

How Many Songs Should a Dementia Music Therapy Playlist Include?

Research and clinical practice converge on a playlist size of 30-60 songs, ideally drawing from 10-15 favorite artists. This range provides enough variety to prevent repetition fatigue while maintaining the familiarity that makes music therapy effective. Too few songs and the playlist becomes monotonous; too many and the therapeutic connection weakens as meaningful tracks get diluted by filler. The critical factor isn’t quantity but personal relevance. A 40-song playlist of music someone genuinely loved will outperform a 200-song collection of era-appropriate hits they merely tolerated.

This is where the “reminiscence bump” becomes essential—songs from ages 18-25 have the highest potential for engagement because this period represents peak memory retention. Neurological research suggests memories formed during these formative years are encoded more deeply, which is why someone who can’t remember yesterday’s breakfast might still recall every word of a song from 1965. However, the reminiscence bump isn’t universal. Someone who experienced trauma during their late teens or early twenties may respond better to music from childhood or their thirties. For individuals who immigrated or experienced major cultural shifts, the bump might center on their country of origin rather than where they currently live. Playlist building requires flexibility and observation rather than rigid adherence to age-based formulas.

Why You Need Two Different Playlist Types

Effective music therapy for dementia requires at least two distinct playlists serving opposite purposes. “Upbeat” playlists featuring faster tempos and major keys support light exercise, social engagement, and mood elevation. “Calming” playlists with slower tempos and gentler arrangements help lower blood pressure, reduce agitation, and ease transitions like bedtime or bathing. Using the wrong playlist type at the wrong time can backfire.

Playing energizing music during an agitated episode may escalate rather than soothe the person. Conversely, calming music during a social activity might dampen engagement when connection is the goal. Caregivers need clear labeling and guidance about which playlist serves which purpose—and the judgment to recognize when circumstances call for switching. A practical approach involves color-coding or clearly naming playlists by function rather than genre. “Morning Energy” and “Evening Wind-Down” communicate purpose better than “Motown Hits” or “Classical.” Some care facilities have found success with three-tier systems: high energy for activities, moderate for daily routines, and low for rest or distress—though managing more playlists requires more training and coordination.

The Gerdner Protocol: Timing Music for Maximum Impact

Perhaps the most underutilized aspect of music therapy for dementia is strategic timing. The Gerdner Protocol, developed through research at Stanford University, recommends playing music 30 minutes before anticipated stress points to potentially avoid distress altogether. This means starting calming music half an hour before a typically difficult transition like bathing, rather than waiting until agitation has already begun. This proactive approach represents a fundamental shift from reactive care. Rather than using music as an intervention after behavioral symptoms emerge, caregivers can use it as prevention.

For someone who consistently becomes agitated at sundown, beginning their calming playlist at 3:30 PM rather than 5:00 PM may eliminate the episode entirely. The research on therapy duration supports this sustained approach—music therapy proves most effective when it spans at least 12 weeks with at least 16 sessions totaling at least 8 hours of exposure. The limitation here is predictability. Proactive timing works when stress triggers follow patterns. For unpredictable agitation, caregivers still need the calming playlist ready for reactive use. Additionally, some individuals with advanced dementia may lose the capacity to anticipate or be soothed preventatively, making immediate intervention more appropriate than scheduled prevention.

Headphones Versus Speakers: Choosing the Right Delivery Method

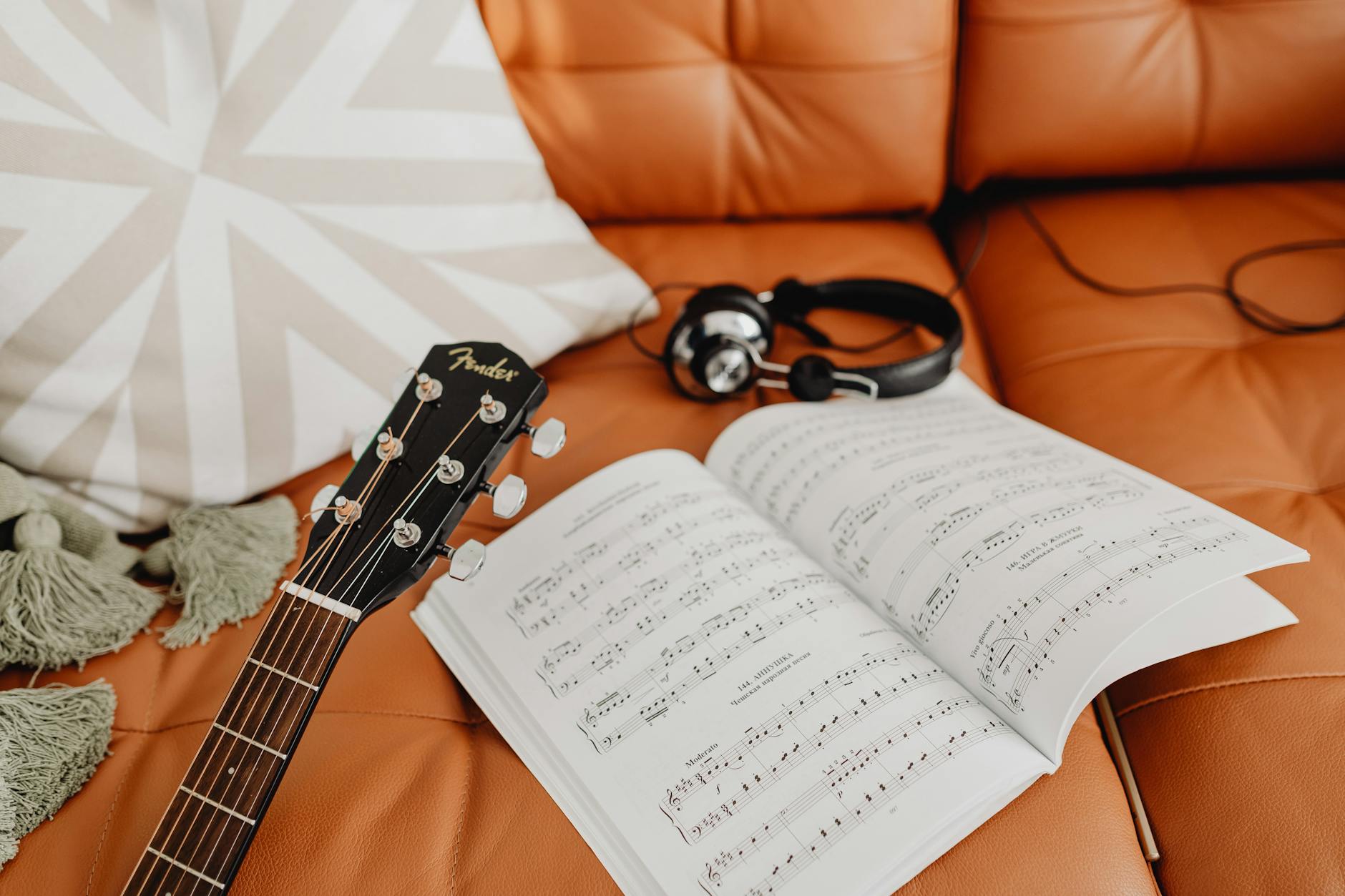

The choice between headphones and speakers depends entirely on individual comfort preference, cognitive stage, and care setting—there’s no universally superior option. Headphones provide immersive listening that blocks environmental noise, potentially deepening engagement and making music more effective in chaotic environments like busy care facilities. Some individuals find headphones uncomfortable or frightening, particularly those with advanced dementia who may not understand what’s on their head. Speakers allow music to fill a room and can benefit multiple people simultaneously during group activities.

They also permit easier monitoring of responses and don’t require the person to tolerate something touching their head or ears. However, speakers compete with background noise and may disturb others nearby. In shared living situations, this creates practical constraints that headphones avoid. The tradeoff often comes down to this: headphones maximize individual therapeutic impact but require tolerance and supervision; speakers maximize flexibility and comfort but dilute the immersive quality. Many successful programs keep both options available and let the person’s reactions guide the choice on any given day.

Common Mistakes That Undermine Music Therapy Effectiveness

The most damaging mistake is substituting generic “dementia playlists” for personalized music based on life history. While streaming services offer pre-made therapeutic playlists, research consistently shows personalized music outperforms these generic alternatives. Someone who hated Frank Sinatra won’t suddenly find him therapeutic because he’s from the right era. Worse, disliked music can increase agitation rather than reduce it. Another frequent error involves volume. Music played too quietly gets lost in environmental noise and loses impact; music played too loudly becomes overwhelming rather than soothing.

Finding the right volume requires attention to individual hearing loss, ambient noise levels, and real-time response. What worked yesterday may need adjustment today. Perhaps most critically, many programs underestimate the importance of environmental preparation. Playing therapeutic music in a chaotic, brightly lit room with competing conversations undermines the intervention. Creating a calm environment with reduced background noise and comfortable seating—before pressing play—dramatically improves outcomes. The music itself is only one component of effective therapy.

Building a Playlist Through Life Story Investigation

Uncovering someone’s meaningful music requires detective work, especially for individuals who can no longer communicate their preferences clearly. Family interviews should explore not just favorite artists but contexts: What played at their wedding? What songs remind them of their first car, their children’s childhoods, their career? Religious music, national anthems, and songs from cultural celebrations often carry deep significance that “favorite artist” questions miss entirely.

Playlist for Life trains volunteers in this investigative approach, teaching techniques for prompting memories and interpreting reactions. For someone without available family, care staff can observe responses to different musical styles, decades, and genres—watching for toe-tapping, humming, emotional expression, or increased alertness as signals of connection.

The Measurable Benefits and Realistic Expectations

The documented benefits of properly implemented music therapy for dementia are substantial: reductions in psychotropic medication use, reduced use of restraints, decreased stress and wandering, fewer falls, significant improvements in verbal fluency, and reduced anxiety, depression, and apathy. A January 2026 National Endowment for the Arts study found 33% lower dementia incidence among people who frequently listened to music and played instruments, with 22% lower incidence of other cognitive impairments—though these prevention statistics apply to lifelong engagement rather than therapeutic intervention after diagnosis. Music therapy will not cure dementia or halt its progression.

It will not work equally well for everyone, and its effects may diminish as the disease advances. Some days the music will seem to reach someone profoundly; other days, there will be no visible response. These limitations don’t invalidate the intervention—they simply require realistic expectations. Music therapy remains one of the most evidence-supported non-pharmacological approaches available, particularly for behavioral symptoms that otherwise often lead to medication with significant side effects.