Parkinson’s disease erodes physical confidence through a relentless accumulation of small defeats””the coffee cup that slips from a trembling hand, the sidewalk crack that becomes an insurmountable obstacle, the familiar stairs that now demand complete concentration. This loss happens gradually, often so slowly that people with Parkinson’s find themselves avoiding activities they once did automatically, not because the disease has made them impossible, but because the unpredictability of their own body has made them afraid to try. The restoration of physical confidence requires addressing both the mechanical challenges of movement and the psychological weight of repeated failures, typically through a combination of targeted physical therapy, environmental modifications, and deliberate practice of feared activities in controlled settings. Consider Margaret, a 68-year-old retired teacher who realized her confidence had vanished not when she fell, but when she stopped walking to her mailbox.

The distance hadn’t changed. Her ability to cover it, on most days, remained intact. What disappeared was her willingness to trust that her legs would cooperate, that her feet would clear the curb, that she wouldn’t freeze mid-stride with a neighbor watching. This pattern””capability exceeding confidence””affects the majority of people living with Parkinson’s and often accelerates physical decline by encouraging inactivity. This article examines how the disease dismantles physical self-assurance, why this psychological dimension matters as much as motor symptoms, and what approaches help rebuild the trust between a person and their body.

Table of Contents

- How Does Parkinson’s Disease Gradually Undermine Physical Confidence?

- The Hidden Connection Between Motor Symptoms and Self-Perception

- Why Freezing Episodes Deliver the Hardest Blow to Independence

- Rebuilding Trust Through Targeted Physical Rehabilitation

- When Medication Fluctuations Create a Moving Target

- The Role of Home Modification in Preserving Autonomy

- How Exercise Programs Restore Both Strength and Self-Assurance

- The Importance of Psychological Support Alongside Physical Therapy

- Conclusion

How Does Parkinson’s Disease Gradually Undermine Physical Confidence?

The erosion begins with motor symptoms that introduce uncertainty into previously automatic movements. Tremor makes hands unreliable for tasks requiring precision. Bradykinesia””the slowing of movement””transforms quick reflexes into delayed responses. Rigidity removes the fluid adaptability that allows bodies to recover from small stumbles. Perhaps most insidiously, postural instability compromises the unconscious adjustments that keep people upright. Each symptom alone creates manageable challenges, but their combination produces a body that can no longer be trusted to perform on demand. The psychological impact compounds because Parkinson’s symptoms fluctuate unpredictably.

Someone might walk steadily through a grocery store one hour and freeze in a doorway the next. This inconsistency prevents the development of reliable compensatory strategies. A person cannot simply learn to move more slowly if the required slowness varies from morning to afternoon. Research published in the Journal of Parkinson’s disease found that symptom unpredictability correlated more strongly with activity avoidance than symptom severity itself””people feared not knowing what their body would do more than they feared what it actually did. Social exposure accelerates confidence loss. Tremor visible to others during a restaurant meal, freezing episodes that block store aisles, the shuffling gait that draws concerned looks””these public moments create anticipatory anxiety that compounds motor difficulties. Studies using wearable sensors have documented that people with Parkinson’s move more hesitantly when they know they’re being observed, creating a feedback loop where social anxiety worsens the very symptoms causing embarrassment. However, this social dimension also offers therapeutic opportunity: carefully structured group exercise programs often restore confidence faster than solitary practice because they normalize struggle and provide peer models of successful adaptation.

The Hidden Connection Between Motor Symptoms and Self-Perception

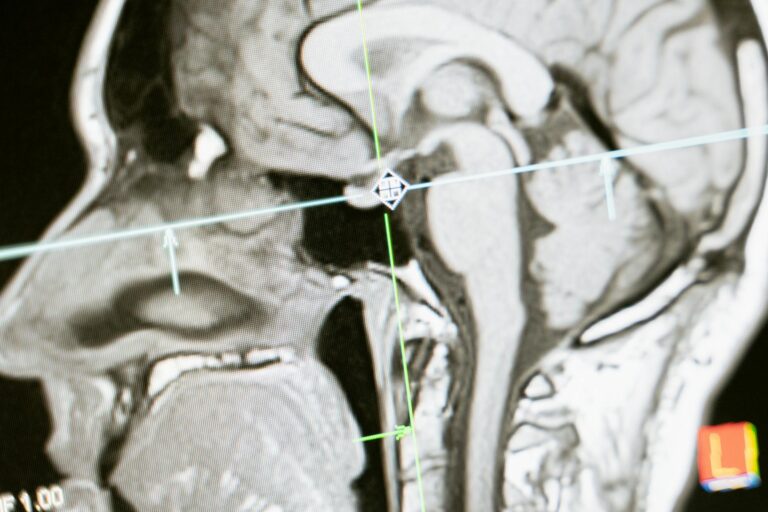

Physical confidence in Parkinson’s depends not just on what the body can do, but on what the person believes it can do””and these two realities frequently diverge. Neuroimaging studies reveal that Parkinson’s affects brain regions involved in predicting movement outcomes, meaning people may genuinely misperceive their physical capabilities. Some underestimate what they can safely accomplish, leading to unnecessary restriction. Others overestimate their stability, increasing fall risk. Neither perception serves them well, and correcting these misperceptions requires more than reassurance. The proprioceptive system””the body’s internal sense of position and movement””deteriorates in Parkinson’s, further disconnecting people from accurate self-assessment. Someone might feel they’re taking normal-sized steps while actually shuffling.

They might perceive themselves as standing upright while leaning significantly. This sensory unreliability makes it difficult to learn from experience because the internal feedback that typically guides motor learning no longer matches external reality. Video feedback has emerged as a powerful intervention precisely because it provides objective information that proprioception can no longer deliver. However, if cognitive impairment accompanies motor symptoms””which occurs in roughly 25-30% of people with Parkinson’s within 10 years of diagnosis””the relationship between actual ability and perceived ability becomes even more complex. Cognitive changes can impair insight, making someone unaware of genuine limitations while simultaneously aware enough to feel frustrated. Families often find themselves navigating the difficult territory between encouraging independence and preventing harm, with no clear guidelines for where capability ends and risk begins. Occupational therapy assessments that evaluate both motor and cognitive function in real-world tasks provide more reliable guidance than either the person’s self-report or family observations alone.

Why Freezing Episodes Deliver the Hardest Blow to Independence

Freezing of gait””the sudden, temporary inability to initiate or continue walking despite the intention to move””represents perhaps the most confidence-destroying symptom of Parkinson’s disease. Unlike tremor or slowness, which can be anticipated and accommodated, freezing strikes without warning. Feet feel glued to the floor. The harder someone tries to move, the more impossible movement becomes. Episodes typically last seconds to a minute, but the psychological impact endures far longer. The locations where freezing occurs become associated with danger. Doorways, narrow passages, crowded spaces, and turning movements all serve as common triggers, which means the home environment itself becomes a landscape of potential failure.

One study tracking home movement patterns found that people with freezing episodes gradually modified their routes to avoid known trigger points, sometimes adding significant distance to reach adjacent rooms. This avoidance protects against freezing in the short term but prevents the desensitization that might reduce freezing frequency over time. Consider Robert, a 72-year-old former engineer whose freezing episodes began occurring at his kitchen threshold. Rather than practice moving through the doorway with cueing strategies, he began entering the kitchen only from the garage entrance, which required going outside and around the house. His wife initially supported this adaptation as practical problem-solving. Only when winter weather made the outdoor route dangerous did they seek help from a physical therapist, who discovered that Robert could move through the kitchen doorway reliably when using rhythmic auditory cues””a metronome beat that external research has shown reduces freezing in approximately 70% of patients. The solution had existed all along; fear had prevented its discovery.

Rebuilding Trust Through Targeted Physical Rehabilitation

Physical therapy for Parkinson’s-related confidence loss differs fundamentally from therapy aimed purely at motor improvement. The goal extends beyond teaching safer movement patterns to include deliberate exposure to feared situations and rebuilding the cognitive-motor integration that allows automatic movement. Programs like LSVT BIG, which emphasizes large-amplitude movements, show benefits partly because exaggerated motion provides clearer proprioceptive feedback, helping restore the sensory-motor calibration that Parkinson’s disrupts. The comparison between conventional physical therapy and Parkinson’s-specific approaches reveals important differences. Standard balance training might focus on standing on unstable surfaces to challenge equilibrium systems.

Parkinson’s-specific training adds cognitive dual-tasking””performing mental arithmetic while balancing, for example””because real-world confidence requires moving while thinking about something else. A therapy session that produces perfect gait in a quiet clinic may not translate to the grocery store where the person must simultaneously navigate, remember their shopping list, and respond to unexpected obstacles. The tradeoff between safety and confidence-building creates ongoing tension in rehabilitation. Highly protective strategies””always using a walker, never walking alone, avoiding all challenging terrain””minimize fall risk but may accelerate the loss of capability and confidence they aim to prevent. Research suggests that controlled exposure to manageable challenges, including supervised practice of recovering from small balance perturbations, actually reduces fall rates compared to pure fall-avoidance strategies. However, this approach requires careful calibration to individual capability and tolerance for risk, and it demands more skilled therapeutic oversight than defensive strategies require.

When Medication Fluctuations Create a Moving Target

Dopaminergic medications that treat Parkinson’s motor symptoms create their own confidence challenge: they work well during “on” periods and poorly or not at all during “off” periods, and the transitions between states can occur unpredictably. A person might leave home during an “on” period, confident in their movement, only to experience medication wearing off mid-errand. This variability makes it difficult to plan activities and nearly impossible to develop consistent confidence. The phenomenon of “wearing off” typically emerges several years after beginning levodopa treatment and affects most patients eventually. Movement capability can shift dramatically within an hour. Families learn to schedule outings immediately after medication takes effect, but this window-based living constrains spontaneity and reinforces the message that the body cannot be trusted.

Some people respond by avoiding activities that require sustained mobility; others gamble on timing and face public episodes when the medication wears off earlier than expected. A limitation of current medical management is that adjusting medications to smooth these fluctuations often requires accepting tradeoffs. More frequent dosing may reduce off-time but increases the risk of dyskinesia””involuntary movements that carry their own confidence costs. Extended-release formulations provide smoother coverage but offer less moment-to-moment control. Surgical interventions like deep brain stimulation can reduce fluctuations significantly, but candidacy requirements exclude many patients, and the surgery carries its own risks. No perfect solution exists; management becomes an ongoing negotiation between competing imperfect options.

The Role of Home Modification in Preserving Autonomy

Environmental changes can restore practical confidence even when physical capacity remains unchanged. Grab bars installed at strategic locations transform bathroom trips from anxiety-provoking expeditions to manageable routines. Improved lighting eliminates the visual ambiguity that triggers freezing. Removing loose rugs and trailing cords addresses fall hazards that might not threaten someone without Parkinson’s but become genuine dangers when balance and reaction time are compromised. The psychological dimension of home modification matters as much as the physical. A home filled with obvious accessibility equipment can feel like a medical facility, constantly reminding inhabitants of limitation.

Thoughtful design integrates safety features unobtrusively””furniture arrangements that provide steady surfaces to touch while walking, color contrasts at level changes that guide the eye without announcing disability. The goal is an environment that supports capable movement rather than one that announces incapacity. For example, one home modification specialist working with a retired professor installed a library ladder rail system throughout the main living areas. The brass rails, mounted at hip height, provided continuous support surfaces while appearing decorative rather than medical. The professor reported that visitors never identified the rails as accessibility equipment, and he stopped planning his movements around furniture locations. This approach costs significantly more than standard grab bars, illustrating the tradeoff between functionality and aesthetics that families must navigate based on priorities and resources.

How Exercise Programs Restore Both Strength and Self-Assurance

Structured exercise programs designed for Parkinson’s disease accomplish more than physical conditioning””they provide repeated evidence that the body can still perform, gradually overwriting the narrative of decline with experiences of capability. Programs ranging from boxing-based training to dance therapy share a common mechanism: they demand physical effort at the edge of current ability while providing enough structure and support to ensure success more often than failure.

Tai chi deserves specific mention because randomized trials have demonstrated not just improved balance and reduced falls but also improved confidence scores that persist months after formal training ends. The practice’s emphasis on slow, controlled weight shifts directly addresses the postural instability underlying much of Parkinson’s-related fear, while its meditative quality may help interrupt the anxiety-tension-worsening symptom cycle. However, access remains limited in many areas, and video-based home practice appears less effective than in-person instruction with qualified teachers.

The Importance of Psychological Support Alongside Physical Therapy

The fear and avoidance that characterize lost physical confidence represent psychological phenomena as much as physical ones, yet mental health treatment remains underutilized in Parkinson’s care. Cognitive behavioral therapy adapted for Parkinson’s can identify and challenge the catastrophic thinking patterns that transform ordinary activities into perceived dangers. A single fall becomes, in an anxious mind, proof that falling is inevitable””a belief that restricts activity far beyond what the fall itself necessitated. Support groups offer a different therapeutic mechanism: normalization. Seeing peers with similar symptoms navigate daily challenges successfully provides modeling that no amount of professional instruction can replace.

When someone watches a fellow group member with visible tremor pour coffee without incident, or freezing-prone member cross a threshold using a stepping-over-imaginary-obstacle cue, they witness possibility rather than just hearing about it. The “if they can, maybe I can” thought represents a more powerful motivator than clinical reassurance. Looking forward, research increasingly recognizes that Parkinson’s disease demands integrated treatment addressing motor, cognitive, and psychological dimensions simultaneously. The medical model that treats tremor with medication, balance with physical therapy, and anxiety as a separate concern fails to address how these domains interact. Emerging multidisciplinary programs that coordinate neurologist, physical therapist, occupational therapist, and mental health provider interventions show promise for addressing the whole person rather than isolated symptoms. Until such integrated care becomes standard, people with Parkinson’s and their families often must assemble their own care teams and advocate for the comprehensive approach that confidence restoration requires.

Conclusion

Physical confidence in Parkinson’s disease erodes through accumulating experiences of bodily unreliability, unpredictable symptom fluctuations, and the social exposure of visible disability. This erosion matters because lost confidence restricts activity more than the disease itself typically requires, accelerating physical decline and diminishing quality of life. Restoration demands addressing both the mechanical challenges of movement and the psychological weight of repeated failures, through physical therapy that includes deliberate exposure to feared situations, environmental modifications that support capable movement, exercise programs that provide evidence of ongoing ability, and psychological support that interrupts catastrophic thinking patterns. The path forward requires recognizing that physical confidence represents a legitimate treatment target, not merely a side effect to be accepted.

Families and healthcare providers who focus exclusively on preventing falls may inadvertently accelerate the loss of capability they hope to preserve. The goal is not perfect safety but rather the preservation of meaningful activity within acceptable risk. This balance point differs for each person and shifts as the disease progresses, requiring ongoing reassessment rather than fixed rules. With appropriate support, many people with Parkinson’s discover they can continue participating in activities they had abandoned, not because their disease improved but because their confidence””and the skills that support it””was rebuilt through deliberate effort.