Fear of falling isn’t just a psychological concern for people with Parkinson’s disease””it’s a rational response to a genuine physical threat that affects their daily independence and quality of life. The statistics paint a stark picture: 45-68% of people with Parkinson’s disease fall each year, a rate double that of age-matched older adults without the condition. This fear becomes a self-reinforcing cycle where anxiety about falling leads to reduced activity, which accelerates physical decline, which in turn increases actual fall risk. Understanding this cycle is the first step toward breaking it.

Consider someone like Brian Hall, who documented his journey in the memoir “Not Afraid to Fall.” Hall first experienced Parkinson’s symptoms in 1976 at just 14 years old””a reminder that this disease doesn’t discriminate by age and that learning to navigate fall risk becomes a lifelong adaptation for many. His story represents the millions now affected: 1.1 million Americans currently live with Parkinson’s disease, a number expected to reach 1.2 million by 2030. This article examines the relationship between Parkinson’s disease and fear of falling through current research, including 2025 data from ongoing studies. We’ll explore why falls happen so frequently in this population, how fear itself becomes a risk factor, what interventions show promise, and the practical strategies that help people with Parkinson’s maintain their mobility and confidence.

Table of Contents

- Why Do People with Parkinson’s Disease Fall So Often?

- The Psychology of Fear: When Anxiety Becomes Its Own Risk Factor

- The Full Spectrum of Fall Risk Factors in Parkinson’s Disease

- Practical Strategies for Reducing Fall Risk

- When Standard Approaches Don’t Work: Complex Cases and Limitations

- The Economic and Societal Impact of Falls in Parkinson’s Disease

- Looking Forward: Research and Hope

- Conclusion

Why Do People with Parkinson’s Disease Fall So Often?

Parkinson’s disease attacks the very systems that keep us upright and balanced. The loss of dopamine-producing neurons affects motor control, creating the characteristic tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia (slowness of movement) that make quick corrective movements difficult or impossible. When a person without Parkinson’s stumbles, their body automatically adjusts””shifting weight, extending an arm, taking a compensatory step. For someone with Parkinson’s, these reflexive responses are delayed or diminished.

Pooled research estimates tell a troubling story: one in two persons with Parkinson’s falls at least once within a given time period, and one in three falls at least twice. In prospective studies that followed patients over time, 60.5% reported at least one fall (with ranges as wide as 35-90% depending on the study population), while 39% experienced recurrent falls. For those who fall repeatedly, the numbers are staggering””recurrent fallers average between 4.7 and 67.6 falls per person per year, with an overall average of 20.8 falls annually. A 2025 medRxiv study analyzing 6,977 visits from 3,100 participants quantified this elevated risk precisely: people with diagnosed Parkinson’s disease had 1.66 times higher odds of falling compared to those with prodromal alpha-synucleinopathy (the precursor stage before full diagnosis). This odds ratio of 1.66 with a 95% confidence interval of 1.46-1.89 represents strong statistical evidence that fall risk increases substantially as the disease progresses from its earliest stages to clinical diagnosis.

The Psychology of Fear: When Anxiety Becomes Its Own Risk Factor

Here’s the paradox that makes fear of falling so insidious: the fear itself becomes a risk factor for falls. When someone becomes afraid of falling, they often restrict their activities, avoid walking, and move with excessive caution. This protective instinct backfires. Reduced activity leads to muscle weakness, decreased cardiovascular fitness, and loss of the very balance skills that might prevent a fall. The body, like any complex system, deteriorates when not used. Research consistently identifies fear of falling as an independent risk factor for falls in Parkinson’s disease, separate from the physical symptoms of the disease.

This means two people with identical motor symptoms can have very different fall outcomes depending on their psychological relationship with fall risk. The person who maintains activity despite fear typically fares better than the person who retreats to a chair. However, dismissing fear as merely psychological misses important nuances. For people with severe freezing of gait””episodes where the feet suddenly feel glued to the floor””fear is an appropriate response to unpredictable motor symptoms. The goal isn’t to eliminate fear entirely but to calibrate it accurately: enough caution to take reasonable precautions, not so much that it triggers a withdrawal from life. This balance differs for each person depending on their specific symptom profile, home environment, and available support.

The Full Spectrum of Fall Risk Factors in Parkinson’s Disease

falls in Parkinson’s disease rarely have a single cause. Researchers have identified a constellation of risk factors that interact in complex ways. Motor impairment tops the list””disease severity and duration correlate strongly with fall risk. Freezing of gait, where movement suddenly and unpredictably halts, creates obvious hazards. Postural instability, the loss of automatic balance corrections, means small perturbations that a healthy person wouldn’t notice can send someone with Parkinson’s to the ground. Medication effects add another layer of complexity. Dopamine agonists and increased levodopa dosage, while treating primary Parkinson’s symptoms, can contribute to falls through mechanisms like orthostatic hypotension””a sudden drop in blood pressure when standing that causes dizziness or fainting.

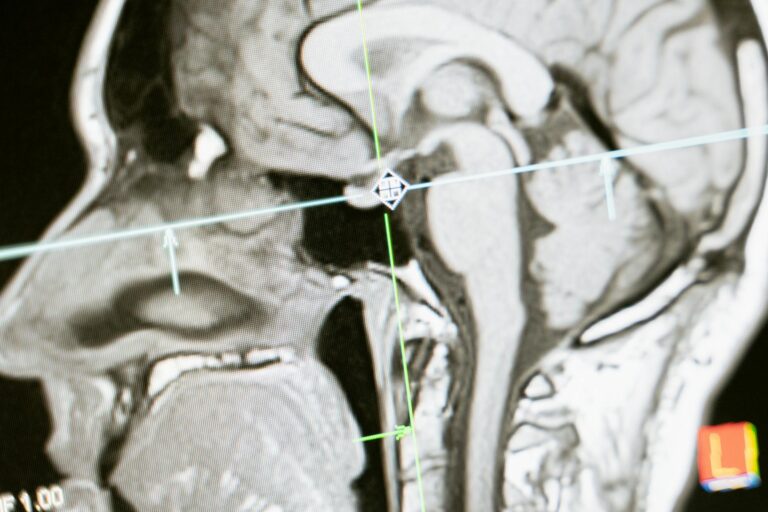

A person might stand up from a chair, experience a blood pressure drop, and fall before they’ve taken a single step. This creates difficult treatment tradeoffs: the same medications that improve mobility can also increase fall risk through cardiovascular side effects. Cognitive impairment emerges as another significant factor. Parkinson’s disease is now understood to affect cognition in many patients, not just movement. When attention and executive function decline, the mental resources needed to navigate complex environments safely become limited. Walking while talking, crossing a busy street, or moving through a cluttered room all require cognitive processing that may be compromised. The AT-HOME PD2 study, which had enrolled 142 participants as of January 2025 (average age 69.2 years, average disease duration 8.9 years), is among several ongoing research efforts examining how these multiple factors interact in real-world settings.

Practical Strategies for Reducing Fall Risk

Fall prevention in Parkinson’s disease requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses physical, environmental, and behavioral factors. Physical therapy specifically designed for Parkinson’s””particularly programs that emphasize balance, gait training, and functional movement””shows consistent benefits. Exercise programs like tai chi, dance-based therapies, and boxing-style workouts have gained popularity because they combine physical training with cognitive demands, addressing multiple risk factors simultaneously. Home modifications represent another practical intervention. Removing throw rugs, improving lighting, installing grab bars in bathrooms, and eliminating clutter from walking paths reduce environmental hazards. These changes won’t prevent all falls””they can’t address the intrinsic motor symptoms of Parkinson’s””but they remove preventable triggers.

The tradeoff is that extensive home modifications can feel like surrendering independence, which some people resist psychologically even when they would benefit physically. Assistive devices occupy a middle ground between doing nothing and major interventions. Canes and walkers provide stability but require learning proper technique; used incorrectly, they can actually increase fall risk. Wheeled walkers with seats allow rest breaks during longer walks, addressing fatigue as a fall contributor. Newer technologies like laser-guided walking cues can help overcome freezing episodes by providing visual targets for stepping. Each option involves balancing effectiveness against the stigma some people associate with mobility aids””a barrier that prevents some from using devices that would genuinely help.

When Standard Approaches Don’t Work: Complex Cases and Limitations

Not everyone responds equally to fall prevention interventions, and it’s important to acknowledge the limitations of current approaches. People with advanced Parkinson’s disease, significant cognitive impairment, or severe freezing of gait may see limited benefit from standard physical therapy protocols. The evidence base for fall prevention comes largely from studies of people with mild to moderate disease; those with more severe symptoms are often excluded from trials or show smaller treatment effects. Medication management for fall risk also has clear limits. While adjusting dopaminergic medications can sometimes reduce orthostatic hypotension or improve motor function, every change involves tradeoffs.

Reducing medication to minimize hypotension might worsen motor symptoms that themselves increase fall risk. Adding medications to raise blood pressure can have cardiovascular consequences. There’s rarely a clean solution, only a choice among imperfect options. The psychological burden of falls and fear of falling can also exceed what standard interventions address. Depression and anxiety are common in Parkinson’s disease independent of fall concerns, and when layered with the trauma of recurrent falls, can create psychological suffering that physical therapy alone cannot resolve. Some people benefit from counseling or support groups specifically for Parkinson’s disease, where they can process their experiences with others who understand the daily reality of living with unpredictable motor symptoms.

The Economic and Societal Impact of Falls in Parkinson’s Disease

Falls don’t just affect individuals””they ripple outward to families, healthcare systems, and society. The combined direct and indirect costs of Parkinson’s disease reached an estimated $52 billion per year in 2020 and are projected to hit $61.5 billion by 2025. Falls contribute substantially to this burden through emergency room visits, hospitalizations for fractures and head injuries, increased need for home care, and earlier transitions to assisted living or nursing home care.

For families, a fall often marks a turning point. Adult children may need to take time off work to care for a parent recovering from a hip fracture. Spouses become informal caregivers, monitoring constantly for fall risk, which strains relationships and creates its own health consequences for the caregiver. The financial impact extends beyond direct medical costs to lost wages, home modifications, and the opportunity costs of time spent on care rather than other pursuits.

Looking Forward: Research and Hope

Parkinson’s disease is the second-most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s, and that prevalence drives substantial research investment. Current studies like the AT-HOME PD2 project are moving fall research out of clinical settings and into patients’ actual living environments, using wearable sensors and remote monitoring to capture what really happens in daily life rather than what can be observed during brief clinic visits.

Emerging interventions include virtual reality balance training, smart home systems that detect fall risk factors, and even implanted devices that may one day provide real-time compensation for motor symptoms. None of these are ready for widespread use, but they represent active areas of development. For people living with Parkinson’s today, the most important message may be that fall risk, while serious, is modifiable””not eliminated, but reduced through sustained effort, appropriate intervention, and honest acceptance of the challenges the disease presents.

Conclusion

Fear of falling in Parkinson’s disease is both a rational response to genuine danger and a psychological burden that can worsen outcomes when it leads to inactivity and withdrawal. The statistics are sobering””fall rates double those of age-matched peers, with one in two people with Parkinson’s falling at least once annually. Yet within these numbers lies room for intervention. Physical therapy, home modifications, assistive devices, medication optimization, and psychological support all offer pathways to reduce risk and maintain quality of life.

The story of Parkinson’s disease and falling is ultimately one of adaptation rather than defeat. People learn to move differently, to modify their environments, to accept help when needed, and to continue engaging with life despite increased vulnerability. The goal isn’t to pretend falls don’t matter or to live in constant fear of them, but to find a sustainable middle ground””taking reasonable precautions while refusing to let fear dictate the boundaries of one’s life. With 1.1 million Americans currently living with this diagnosis and that number rising, the accumulated wisdom of those who have walked this path before becomes an invaluable resource for those just beginning it.