Understanding tau spread along brain networks has become one of the most significant areas of research in dementia science, offering crucial insights into how neurodegenerative diseases progress and potentially how they might be slowed or stopped. Tau protein, a molecule essential for healthy brain function, can become corrupted and spread through interconnected brain regions in a pattern that closely follows the brain’s neural pathways. This spreading process underlies much of the cognitive decline seen in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, making it a central focus for researchers and clinicians working to develop effective interventions. The question of how tau pathology moves through the brain addresses one of the most pressing mysteries in neuroscience: why do certain brain regions deteriorate in a predictable sequence during dementia? For decades, scientists observed that tau tangles appeared first in specific areas, then progressively emerged in connected regions, but the mechanisms driving this spread remained elusive.

Recent advances in brain imaging, molecular biology, and network science have begun to reveal that tau doesn’t spread randomly””it travels along the same neural highways that healthy brain signals use for communication, hijacking the brain’s own connectivity architecture. By the end of this article, readers will understand the fundamental biology of tau protein, the mechanisms by which it spreads between neurons, why brain network connectivity matters for disease progression, and what this knowledge means for diagnosis, treatment, and caregiving. This information is particularly relevant for families affected by dementia, healthcare professionals seeking to understand emerging research, and anyone interested in the cutting edge of brain science. The implications extend beyond academic interest””understanding tau spread patterns may eventually allow doctors to predict disease trajectories and target interventions more precisely.

Table of Contents

- What Is Tau Protein and Why Does It Spread Along Brain Networks?

- How Brain Network Connectivity Determines Tau Spreading Patterns

- The Relationship Between Tau Spread and Cognitive Decline

- Current Research on Blocking Tau Spread in Brain Networks

- Challenges in Detecting and Measuring Tau Spread Along Brain Networks

- Implications for Caregiving and Family Support

- How to Prepare

- How to Apply This

- Expert Tips

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Tau Protein and Why Does It Spread Along Brain Networks?

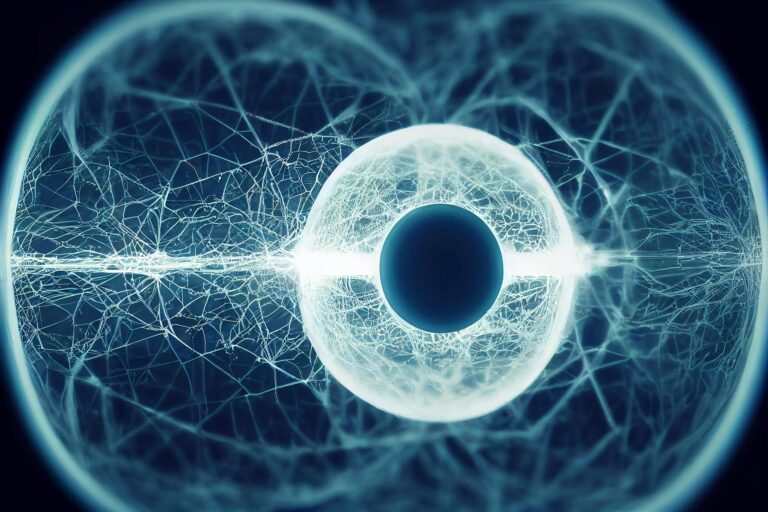

Tau protein serves an essential function in healthy neurons, acting like railroad ties that stabilize microtubules””the structural scaffolding that helps transport nutrients and cellular materials throughout nerve cells. In a healthy brain, tau maintains these transport highways in proper working order, enabling neurons to communicate efficiently and maintain their complex branching structures. However, when tau becomes abnormally modified through a process called hyperphosphorylation, it detaches from microtubules and begins clumping together into twisted fibers known as neurofibrillary tangles. These tau tangles don’t remain confined to their original location.

Research has demonstrated that abnormal tau can spread from neuron to neuron through multiple mechanisms, including release into the space between cells and uptake by neighboring neurons, transfer through direct cell-to-cell contact, and transmission via exosomes””small membrane-bound packages that neurons use to communicate. Once pathological tau enters a healthy neuron, it can induce the normal tau proteins in that cell to misfold as well, creating a self-propagating cascade that gradually expands through brain tissue. The spread of tau along brain networks follows a predictable pattern because neurons that fire together are wired together. Brain regions with strong functional connections””areas that frequently communicate and coordinate activity””provide efficient pathways for tau transmission. This network-based spread explains why tau pathology begins in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, regions critical for memory, before spreading to temporal, parietal, and eventually frontal cortex regions in a sequence that mirrors the brain’s connectivity map.

- Tau normally stabilizes microtubules, the transport infrastructure within neurons

- Hyperphosphorylation causes tau to detach, misfold, and form toxic aggregates

- Pathological tau spreads between neurons through synaptic connections, following the brain’s wiring diagram

How Brain Network Connectivity Determines Tau Spreading Patterns

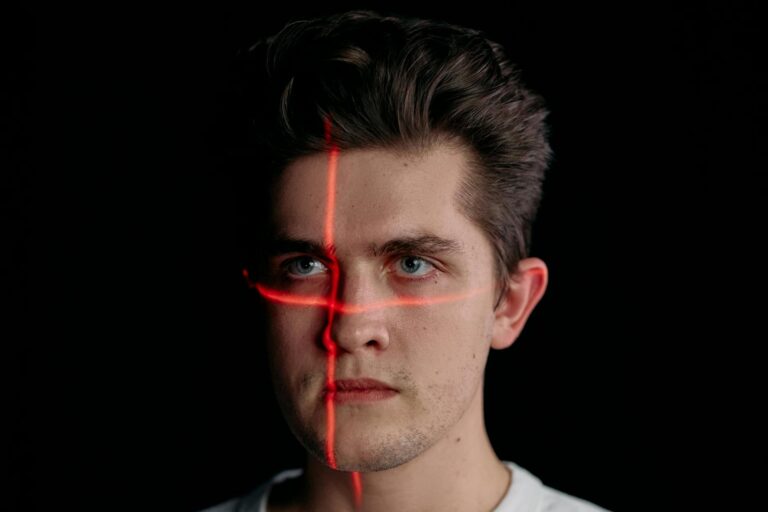

The human brain contains approximately 86 billion neurons connected by trillions of synapses, forming an intricate network that can be mapped using advanced neuroimaging techniques. These connections aren’t random””they form organized patterns with highly connected hub regions that serve as major relay stations for information processing. Research using diffusion tensor imaging and functional MRI has revealed that tau pathology preferentially spreads through these network connections, with the strength and frequency of neural communication predicting where tau will appear next. Studies tracking tau progression in living patients have confirmed this network-based spreading hypothesis. Regions with stronger connectivity to areas already affected by tau tangles show higher rates of subsequent tau accumulation compared to regions with weaker connections.

This finding holds true even when accounting for physical distance””two brain areas that are anatomically close but weakly connected show less tau transmission than distant regions with strong functional links. The brain’s hub regions, which have connections to many other areas, appear particularly vulnerable because they serve as convergence points where tau from multiple sources can accumulate. Network neuroscience has identified specific connectivity patterns associated with accelerated tau spread. The default mode network, active during rest and self-referential thought, shows early and prominent tau accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Similarly, the salience network and executive control network develop tau pathology as the disease progresses. understanding these network-specific vulnerabilities has important implications for predicting individual disease trajectories, as patients with different baseline connectivity patterns may experience different rates and patterns of tau spread.

- Brain connectivity mapping reveals that tau spreads along functional neural pathways

- Strongly connected regions develop tau pathology sooner than weakly connected areas

- Hub regions with many connections are particularly vulnerable to tau accumulation

The Relationship Between Tau Spread and Cognitive Decline

The clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies closely track the anatomical progression of tau pathology through brain networks. When tau tangles first appear in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus, patients typically experience subtle memory difficulties””forgetting recent conversations, misplacing objects, or struggling to learn new information. As tau spreads to temporal and parietal regions, language difficulties, spatial disorientation, and problems with complex tasks emerge. Frontal lobe involvement brings changes in personality, judgment, and executive function. Quantitative studies using tau PET imaging have established strong correlations between regional tau burden and specific cognitive deficits.

Patients with greater tau accumulation in left temporal regions show more pronounced language impairment, while those with prominent parietal tau exhibit more severe visuospatial difficulties. This regional specificity explains why dementia manifests differently across individuals””the particular pattern of tau spread through each person’s unique brain network determines their specific constellation of symptoms. The rate of tau spread also predicts the pace of cognitive decline. Longitudinal studies following patients over multiple years have shown that individuals with faster tau accumulation experience more rapid deterioration in memory, language, and daily functioning. This relationship offers hope for intervention””if tau spread can be slowed through medication or other approaches, cognitive decline might be proportionally reduced. Current research focuses on identifying the critical points in the spreading process where intervention might be most effective.

- Cognitive symptoms directly reflect which brain regions have accumulated tau pathology

- Regional tau burden correlates with specific functional impairments

- Faster tau spread predicts more rapid cognitive decline

Current Research on Blocking Tau Spread in Brain Networks

Multiple therapeutic strategies are under investigation to interrupt the network-based spread of tau pathology. Anti-tau antibodies represent one promising approach, designed to bind pathological tau in the extracellular space before it can be taken up by healthy neurons. Several of these immunotherapies have advanced to clinical trials, with researchers carefully measuring tau PET signal changes to assess whether the antibodies successfully reduce tau accumulation in connected brain regions. Another avenue of research targets the cellular mechanisms that enable tau transmission between neurons. Scientists are investigating compounds that could block tau release from affected neurons, prevent uptake by recipient cells, or enhance the brain’s natural ability to clear abnormal tau.

Small molecule drugs targeting tau aggregation directly aim to prevent the initial formation of toxic tau species that can spread through networks. Gene therapy approaches seek to reduce tau production or enhance protective mechanisms at the cellular level. Network-based understanding of tau spread has also influenced non-pharmacological interventions. Cognitive reserve””the brain’s resilience built through education, mental stimulation, and social engagement””appears to modify how tau pathology translates into clinical symptoms. Some research suggests that strengthening alternative neural pathways through targeted cognitive training might provide compensation even as primary networks become compromised by tau. Physical exercise, which promotes brain network health and connectivity, is being studied for its potential to slow tau accumulation and spread.

- Anti-tau immunotherapies aim to neutralize pathological tau before it spreads

- Small molecule drugs target tau aggregation and transmission mechanisms

- Non-pharmacological approaches focus on building cognitive reserve and network resilience

Challenges in Detecting and Measuring Tau Spread Along Brain Networks

Despite significant advances, accurately tracking tau spread through brain networks presents substantial technical and biological challenges. Tau PET imaging, while revolutionary, has limitations””current tracers bind more reliably to certain tau conformations than others, potentially underestimating tau burden in some brain regions or disease variants. The relationship between tau PET signal and actual tangle density varies across brain areas, complicating quantitative comparisons of tau accumulation across the network. Individual variability in brain network organization adds another layer of complexity. While general patterns of brain connectivity are shared across humans, each person’s connectome contains unique features shaped by genetics, development, and life experiences. This variability means that tau spread patterns, while following general rules, differ in their specific trajectories across individuals.

Developing personalized predictions of tau spread requires detailed mapping of each patient’s network architecture, a time-intensive and expensive undertaking not yet feasible in routine clinical practice. Temporal dynamics present additional challenges. Tau spread occurs over years to decades, but imaging studies typically capture only snapshots at discrete time points. The relationship between connectivity measured at one moment and tau spread occurring over extended periods remains incompletely understood. Some connections may facilitate tau transmission more during certain disease stages or in specific molecular contexts. Longitudinal studies with frequent imaging assessments are beginning to address these temporal questions but require substantial resources and patient commitment.

- Current tau PET tracers have limitations in detecting all forms of tau pathology

- Individual differences in brain network organization create variability in spread patterns

- The slow timescale of tau spread makes longitudinal tracking challenging

Implications for Caregiving and Family Support

Understanding that tau spreads through brain networks in predictable patterns has practical implications for families and caregivers supporting loved ones with dementia. Recognizing that symptoms follow the geographic progression of pathology can help families anticipate and prepare for changes. When tau moves from memory regions to language areas, communication strategies may need adjustment. As frontal regions become involved, families can expect shifts in personality and judgment that reflect the disease process rather than personal choice.

This knowledge also provides context for the uneven nature of cognitive decline. Patients often retain abilities in some domains while losing function in others, a pattern that directly reflects which brain networks have been affected by tau. A person might remember detailed events from decades past while struggling with recent conversations because long-term memory networks become involved later than those supporting new learning. Understanding these distinctions helps caregivers set appropriate expectations and find remaining strengths to build upon.

How to Prepare

- Learn the typical progression pattern by familiarizing yourself with the Braak staging system, which describes the six stages of tau accumulation from entorhinal cortex through hippocampus to neocortical regions. Understanding this sequence helps anticipate which cognitive functions may be affected as the disease advances and allows for proactive adjustment of care strategies.

- Request appropriate diagnostic testing if dementia is suspected, including neuropsychological evaluation to identify which cognitive domains are affected, structural MRI to assess brain atrophy patterns, and where available, tau PET imaging to directly visualize tau distribution. These assessments provide baseline information for tracking progression.

- Document current cognitive strengths and weaknesses through detailed observation and formal testing. Note which memory types remain intact, how language abilities present, whether visuospatial function shows impairment, and the status of executive function. This documentation becomes invaluable for detecting changes over time.

- Establish relationships with specialists including neurologists, geriatric psychiatrists, and neuropsychologists who understand tau pathology and can interpret imaging findings in the context of clinical presentation. These experts can provide guidance on expected progression based on current tau distribution.

- Create flexible care plans that anticipate likely progression while remaining adaptable to individual variation. Include contingencies for when specific abilities decline, identify support resources for different stages, and establish decision-making frameworks before crises occur.

How to Apply This

- Use knowledge of network-based spread to interpret behavioral changes. When new symptoms emerge, consider which brain regions have likely become involved and adjust caregiving approaches accordingly rather than viewing changes as random or willful.

- Implement compensatory strategies that leverage relatively preserved brain networks. If episodic memory networks are compromised but procedural memory remains intact, focus on establishing routines and automatic behaviors that don’t require conscious recollection.

- Monitor for signs of progression that match expected spreading patterns. Increased language difficulties, emerging visuospatial problems, or changes in judgment may indicate tau has reached new brain regions and signal the need for care plan adjustments.

- Participate in research studies when possible, as longitudinal observation and intervention trials advance understanding of tau spread and may provide access to experimental treatments aimed at slowing network-based progression.

Expert Tips

- Pay attention to symptom clusters rather than isolated problems. Tau spread affects interconnected regions, so difficulties with face recognition, object naming, and reading comprehension might emerge together as temporal networks become involved.

- Recognize that preserved abilities have biological explanations. When someone with significant memory impairment can still play piano or navigate familiar routes, this reflects sparing of the networks supporting these skills rather than inconsistency or faking.

- Consider cognitive rehabilitation strategies that target networks adjacent to those affected by tau. Strengthening alternative pathways may provide compensation even as primary routes become compromised by pathology.

- Understand that mood and behavior changes often precede cognitive symptoms when certain networks are involved early. Depression, apathy, and anxiety may reflect tau in limbic circuits rather than psychological reactions to illness.

- Advocate for comprehensive imaging when available. Combining structural MRI, tau PET, and amyloid PET provides complementary information about network health and pathology distribution that informs prognosis and treatment decisions.

Conclusion

The understanding that tau spreads along brain networks represents a fundamental advance in comprehending how neurodegenerative diseases progress. This knowledge transforms our view of Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies from mysterious deterioration into a mappable process following the brain’s own architecture. The predictable patterns of network-based spread explain why symptoms emerge in characteristic sequences and why certain individuals progress differently based on their unique connectivity profiles.

For families affected by dementia, this scientific understanding offers both practical guidance and a framework for making sense of challenging changes. Knowing that tau pathology follows neural highways allows anticipation of disease course and targeted preparation for specific challenges. For the research and clinical communities, network-based models of tau spread are enabling more precise diagnostic tools, better prognostic predictions, and rationally designed therapeutic interventions aimed at interrupting the spreading process. While much work remains before these insights translate into disease-modifying treatments, the trajectory of discovery provides legitimate grounds for cautious optimism that understanding tau’s journey through brain networks will eventually lead to meaningful ways of slowing or stopping it.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it typically take to see results?

Results vary depending on individual circumstances, but most people begin to see meaningful progress within 4-8 weeks of consistent effort. Patience and persistence are key factors in achieving lasting outcomes.

Is this approach suitable for beginners?

Yes, this approach works well for beginners when implemented gradually. Starting with the fundamentals and building up over time leads to better long-term results than trying to do everything at once.

What are the most common mistakes to avoid?

The most common mistakes include rushing the process, skipping foundational steps, and failing to track progress. Taking a methodical approach and learning from both successes and setbacks leads to better outcomes.

How can I measure my progress effectively?

Set specific, measurable goals at the outset and track relevant metrics regularly. Keep a journal or log to document your journey, and periodically review your progress against your initial objectives.

When should I seek professional help?

Consider consulting a professional if you encounter persistent challenges, need specialized expertise, or want to accelerate your progress. Professional guidance can provide valuable insights and help you avoid costly mistakes.

What resources do you recommend for further learning?

Look for reputable sources in the field, including industry publications, expert blogs, and educational courses. Joining communities of practitioners can also provide valuable peer support and knowledge sharing.