Cholesterol metabolism plays a crucial and multifaceted role in multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic neurological disease characterized by the loss of myelin, the protective sheath around nerve fibers. Understanding this role involves exploring how cholesterol is managed within the brain and immune system, and how disruptions in this balance contribute to MS pathology and progression.

Cholesterol is an essential lipid in the central nervous system (CNS), where it is a major component of myelin. Myelin sheaths, produced by specialized cells called oligodendrocytes, insulate nerve fibers and enable rapid electrical signaling. In MS, the immune system attacks and damages myelin, leading to impaired nerve function. Since cholesterol is a fundamental building block of myelin, its metabolism is intimately linked to the processes of myelin formation, maintenance, and repair.

In the healthy brain, cholesterol metabolism is tightly regulated to support the synthesis of new myelin and maintain neuronal health. Oligodendrocytes rely on cholesterol to produce the lipid-rich myelin membrane. When myelin is damaged in MS, the brain attempts to repair it through remyelination, a process that requires efficient cholesterol synthesis and trafficking. However, in MS, this repair process is often incomplete or fails, partly due to disruptions in cholesterol metabolism.

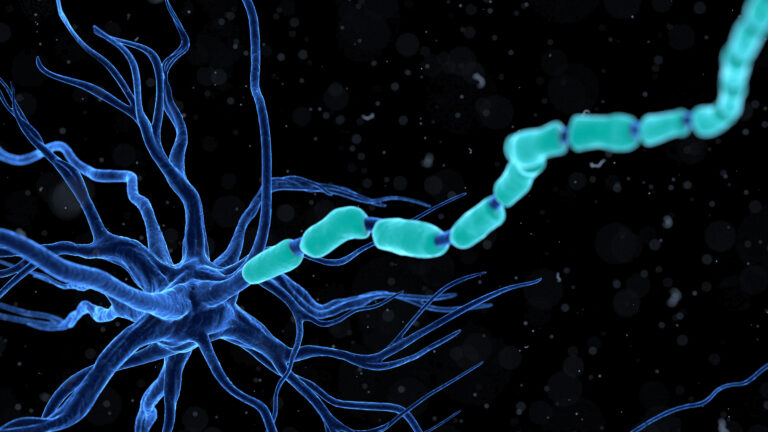

One key aspect is that cholesterol metabolism influences immune cell function. Cholesterol-rich microdomains in cell membranes, known as lipid rafts, are critical for immune cell signaling. Altered cholesterol metabolism can affect how immune cells, such as macrophages and T cells, respond and contribute to inflammation in MS. For example, macrophages can take up modified forms of cholesterol-containing particles, which may promote inflammatory responses or foam cell formation, exacerbating tissue damage.

Recent research has highlighted that in MS and other neurodegenerative diseases, cholesterol homeostasis—the balance of cholesterol synthesis, uptake, and removal—is disturbed. This imbalance can lead to accumulation of cholesterol derivatives that may be toxic or pro-inflammatory, further damaging myelin and neurons. Additionally, proteins that regulate cholesterol metabolism may be dysregulated in MS, impairing the ability of oligodendrocytes to mature and produce myelin effectively.

Emerging studies also suggest that targeting cholesterol metabolism could offer new therapeutic avenues. By restoring cholesterol balance, it may be possible to enhance remyelination and protect neurons. Some experimental treatments focus on modulating cholesterol pathways to promote oligodendrocyte maturation and myelin repair, potentially improving outcomes for MS patients.

In summary, cholesterol metabolism in MS is not just about lipid levels but involves a complex interplay between myelin synthesis, immune cell function, and inflammatory processes. Disruptions in cholesterol homeostasis contribute to the failure of myelin repair and ongoing neurodegeneration. Understanding these mechanisms opens the door to innovative treatments aimed at correcting metabolic dysfunctions to support neural repair and reduce disease progression.