The evidence for the Paleo diet in multiple sclerosis (MS) centers on its potential to reduce inflammation, improve neurological function, and support overall health through nutrient-dense, whole foods. The Paleo diet, often adapted for MS as a modified Paleolithic diet, emphasizes consumption of vegetables, fruits, lean meats, fish, nuts, and seeds while excluding processed foods, grains, dairy, and refined sugars. This dietary pattern aims to reduce immune system activation and oxidative stress, both of which are key factors in MS progression.

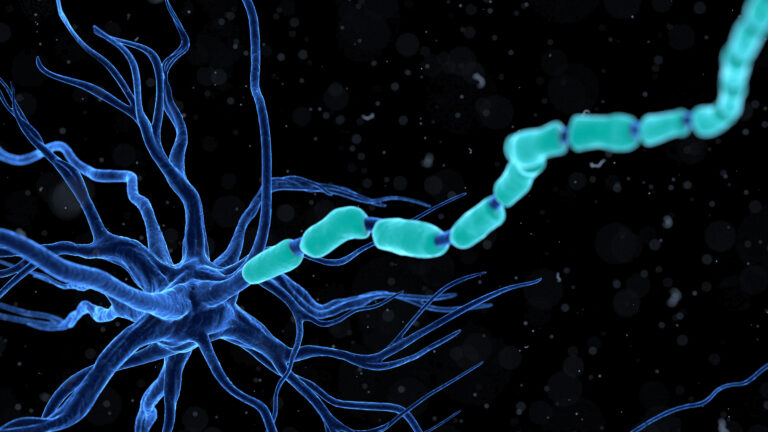

One of the main rationales behind the Paleo diet for MS is its anti-inflammatory potential. MS is characterized by an autoimmune attack on the nervous system, leading to inflammation and damage to the protective myelin sheath around nerves. The Paleo diet’s focus on nutrient-rich, unprocessed foods provides antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals that may help modulate the immune response and reduce inflammation. For example, leafy greens and colorful vegetables are rich in antioxidants and micronutrients that support cellular health and may lower inflammatory markers.

Research related to the Paleo diet in MS often references the Wahls Protocol, a specific modified Paleolithic diet developed by Dr. Terry Wahls. This protocol emphasizes high intake of leafy greens, sulfur-rich vegetables, and nutrient-dense animal proteins, aiming to provide the brain and nervous system with essential nutrients to promote repair and reduce symptoms. Many individuals following the Wahls Protocol report improvements in energy, fatigue, and quality of life, although these reports are largely anecdotal or based on preliminary studies. Controlled clinical trials are still needed to confirm these benefits on a larger scale.

The Paleo diet’s exclusion of gluten and dairy is another aspect thought to benefit some people with MS. Gluten, a protein found in wheat and related grains, has been implicated in promoting inflammation in sensitive individuals. Some studies combining data from various diet interventions suggest that gluten-free Paleo approaches may lead to significant reductions in fatigue, one of the most common and debilitating symptoms of MS. However, this effect may not apply universally, as MS is a heterogeneous disease with varied triggers and responses.

Beyond inflammation, the Paleo diet may support mitochondrial function and reduce oxidative stress, which are important in neurodegeneration seen in MS. By providing healthy fats from sources like fatty fish and nuts, the diet may improve energy metabolism in nerve cells. Some research on ketogenic diets, which share similarities with Paleo in terms of low carbohydrate intake and high fat, shows neuroprotective effects that could be relevant to MS, such as reduced activation of immune cells in the central nervous system and increased production of brain-derived neurotrophic factors that support nerve health.

Despite these promising aspects, the evidence for the Paleo diet in MS is still emerging and not definitive. Most studies are small, short-term, or observational, and there is a lack of large-scale randomized controlled trials. Challenges in following the diet include the need for careful meal planning, potential cost of high-quality foods, and the adjustment period required to shift from a standard Western diet to a more restrictive, nutrient-dense regimen.

In summary, the Paleo diet offers a plausible approach to managing MS symptoms by targeting inflammation, oxidative stress, and nutrient deficiencies through whole, unprocessed foods. While many people with MS report benefits, and some preliminary research supports its use, more rigorous scientific studies are necessary to establish standardized guidelines and confirm long-term efficacy. Individuals interested in the Paleo diet for MS should consult healthcare professionals to tailor dietary changes to their specific health needs and monitor their progress carefully.