The ancient path walking ritual is a profound practice rooted in human history that involves physically moving through a landscape to build what are called memory maps. These memory maps are mental representations of space, formed by linking physical landmarks with stories, emotions, and sensory experiences. This ritual is not just about navigation; it’s a way of embedding knowledge deeply into the mind and body through movement and presence.

At its core, this ritual begins with choosing a path—often one that holds significance culturally or personally—and walking it attentively. The walker engages all senses: sight takes in the shapes and colors of trees or stones; hearing captures birdsong or footsteps on gravel; touch feels the texture of bark or the warmth of sunlight on skin; smell detects earthiness or blooming flowers. Each sensory input becomes an anchor point for memory.

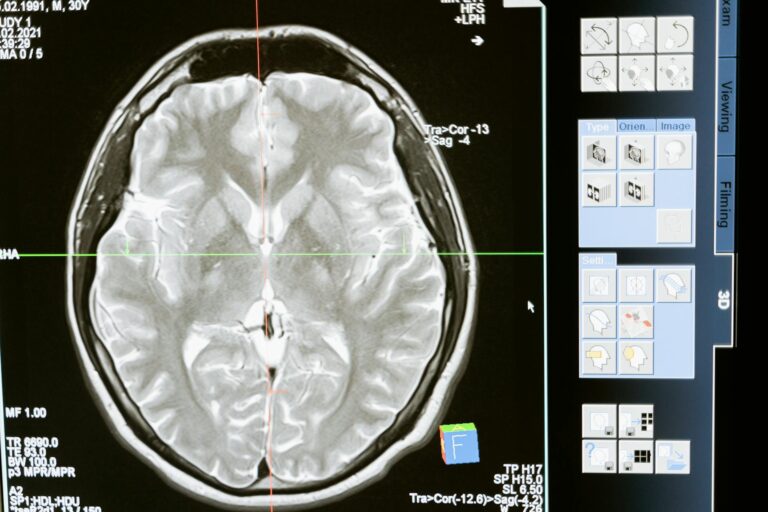

As you walk this ancient path repeatedly over time, your brain starts to create connections between these anchors. This process forms what neuroscientists call spatial memory—an internal map that helps you understand where things are relative to each other without needing external tools like GPS. But unlike modern digital maps, these mental maps carry layers beyond geography: they hold stories told by elders about certain spots, rituals performed at specific clearings, lessons learned from past journeys along the route.

This layering transforms simple navigation into an embodied narrative journey where place and meaning intertwine. For example, passing an old oak tree might remind you not only where you are but also evoke memories of community gatherings held beneath its branches long ago. The act of walking thus becomes a living archive—a way history is preserved through body movement rather than written text.

The rhythm of walking itself plays a crucial role in building these memory maps because repetitive motion enhances focus and retention. Ancient cultures understood this intuitively: many indigenous peoples used pilgrimage routes as both spiritual quests and practical ways to memorize vast territories essential for survival during hunting or trading expeditions.

Moreover, this ritual often includes deliberate pauses at key points along the path where one might recite stories aloud or perform small ceremonies honoring ancestors or natural spirits tied to those locations. Speaking aloud while moving links voice with place in powerful ways—it activates different parts of the brain involved in language processing alongside spatial awareness centers.

In some traditions, participants use objects like stones arranged along paths as mnemonic devices—physical markers that trigger recall when encountered again later during walks or storytelling sessions back home around firesides. These objects become tangible nodes within their mental map networks.

Modern science supports much of what ancient walkers practiced instinctively: studies show that people who navigate environments by foot develop stronger hippocampal activity—the brain region responsible for forming new memories—compared to those relying solely on technology-based directions.

Walking slowly instead of rushing allows deeper engagement with surroundings so subtle details don’t go unnoticed but instead become part of your cognitive map’s fine texture—the difference between knowing “there’s a tree somewhere” versus “there’s an old pine leaning slightly left near moss-covered rocks.”

This slow mindful pace also encourages reflection which strengthens emotional ties linked to places walked frequently over time making those locations feel familiar even if visited after long absences—a phenomenon sometimes described as ‘place attachment.’

In essence then, the ancient path walking ritual builds more than just directional skills; it creates rich multidimensional landscapes inside our minds combining geography with culture, emotion with story—all accessed simply by putting one foot carefully before another while paying close attention to everything around us.

Engaging regularly in such rituals can improve overall cognitive health too since forming complex internal maps exercises neural pathways related not only to spatial reasoning but also creativity and problem-solving abilities connected through associative thinking triggered by environmental cues encountered during walks.

For anyone interested in reconnecting deeply with their environment while sharpening memory naturally without screens or gadgets this practice offers timeless wisdom wrapped up inside something as simple yet profound as taking deliberate steps down an ancient trail known well before modern roads existed —a dance between body movement and mind mapping across time itself.