Alcohol is often overlooked as a serious public health issue largely because it is socially acceptable and deeply embedded in many cultures worldwide. This social acceptance creates a paradox where alcohol’s widespread use masks its significant health, social, and economic harms, leading to underestimation of its risks and insufficient attention to its consequences.

Alcohol consumption is normalized in many societies through traditions, celebrations, and everyday social interactions. It is the second most widely consumed psychoactive substance in places like the UK, after caffeine, and is prevalent in personal and social situations[4]. This normalization can obscure the recognition of alcohol as a potentially harmful substance, unlike illicit drugs which are more stigmatized and thus more readily identified as problematic.

From a medical perspective, alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a major behavioral and psychiatric condition affecting nearly 29% of Americans in their lifetime and at least 8% globally[1]. Despite this high prevalence, most individuals with AUD do not seek treatment. One reason is the historical emphasis on abstinence as the only acceptable treatment goal, which many people find unrealistic or undesirable. Recent shifts in clinical research and policy, such as the FDA endorsing reductions in drinking levels as valid clinical endpoints, reflect a growing recognition that reducing alcohol consumption—even without complete abstinence—can lead to significant health and social improvements[1].

The health burden of alcohol is substantial and often underestimated due to its social acceptability. Globally, alcohol consumption caused an estimated 2.6 million deaths in 2019, accounting for 4.7% of all deaths worldwide[2]. It also contributed to 116 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost, a measure combining years of life lost due to premature death and years lived with disability. Men are disproportionately affected, with higher rates of alcohol-attributable deaths and DALYs compared to women[2]. These figures highlight alcohol’s role as a leading cause of preventable death and disability, yet public perception often downplays these risks.

Perceptions of risky drinking are complex and influenced by social context and personal experience. People often associate risky drinking not just with the amount consumed but with the negative consequences it causes, such as impaired social roles, relationship problems, and safety risks like drink-driving or drink spiking[3]. These situational risks are sometimes recognized only after direct experience or witnessing harm, which can delay awareness and intervention.

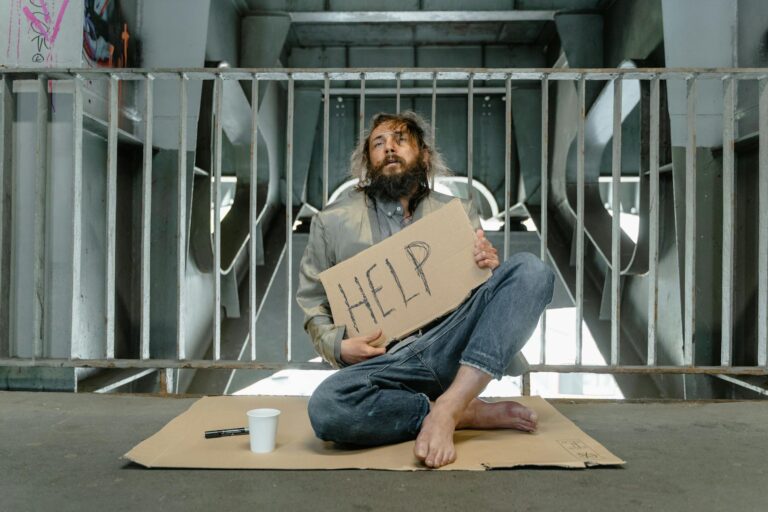

Alcohol’s social acceptability also contributes to significant societal harms that extend beyond the individual drinker. For example, in England, one in five people reported being harmed by others’ drinking within a single year[4]. Children living with alcohol-dependent parents face increased risks of domestic violence, mental health issues, and future addiction problems[4]. Vulnerable populations, such as homeless individuals, experience disproportionately high rates of alcohol-related harm and premature death[4]. These social harms are often overlooked because alcohol use is normalized and integrated into everyday life.

Economic costs further illustrate alcohol’s overlooked impact. The global economic burden of alcohol use is estimated at 2.6% of the world’s gross domestic product, reflecting healthcare costs, lost productivity, and social services[1]. Studies show that reducing drinking levels can lead to up to 52% lower healthcare costs within a year, underscoring the potential benefits of addressing alcohol use more effectively[1].

Despite these facts, alcohol’s social acceptability creates barriers to treatment and prevention. Many people with alcohol problems do not seek help because they do not identify wit