Anxiety can increase the risk of dementia through several interconnected biological, psychological, and behavioral pathways that affect brain health over time. While anxiety itself is a mental health condition characterized by excessive worry, fear, and physiological arousal, its chronic presence can lead to changes in the brain and body that may contribute to the development or acceleration of dementia.

One key mechanism is **chronic inflammation**. Anxiety disorders often trigger prolonged stress responses, activating the body’s stress system repeatedly. This leads to elevated levels of stress hormones like cortisol, which, when persistently high, can cause inflammation in the brain. Chronic inflammation is known to damage brain cells and disrupt neural networks, which are critical for memory and cognitive function. Over time, this inflammatory environment can increase vulnerability to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia.

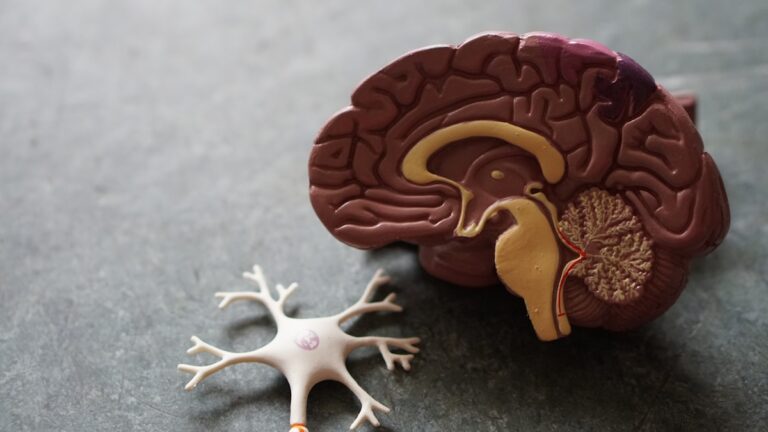

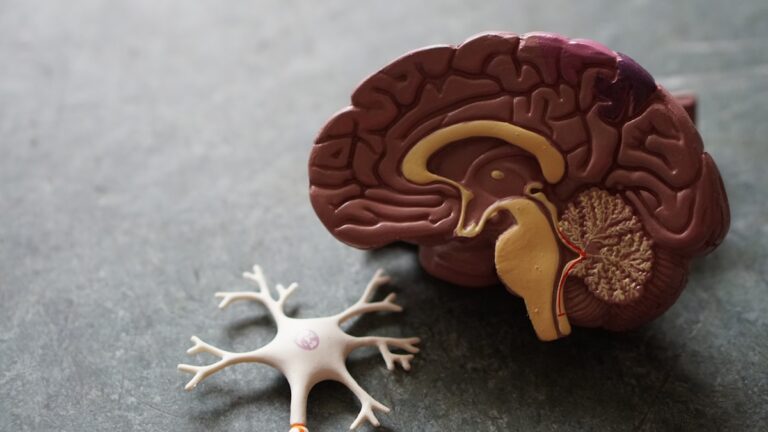

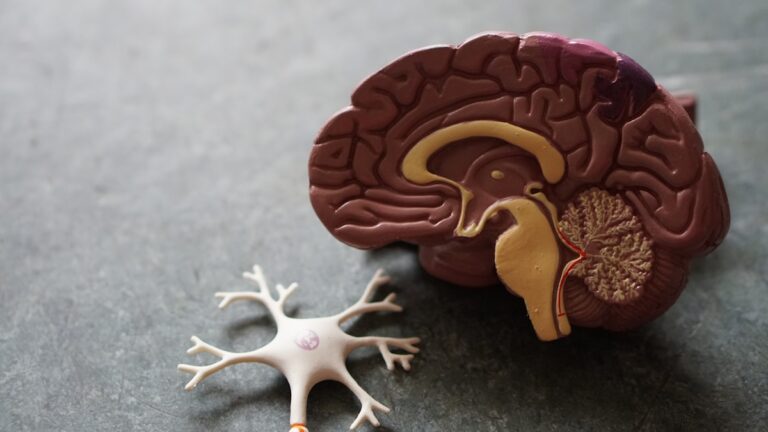

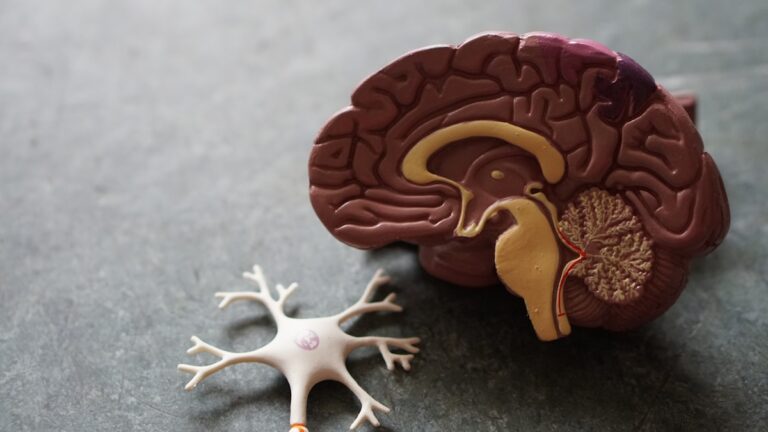

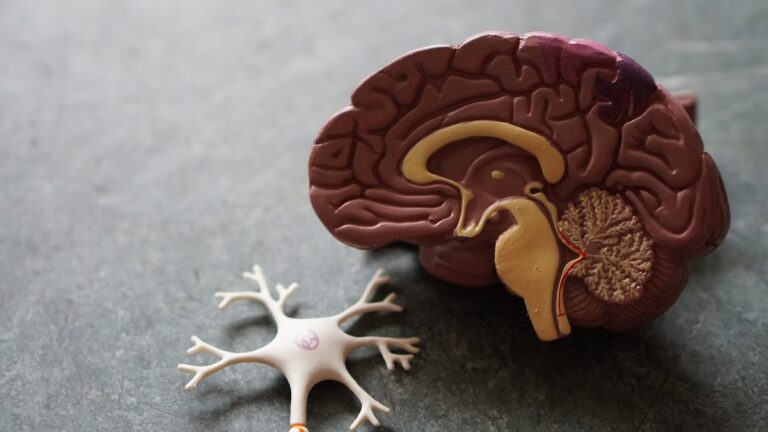

Another important factor is **structural brain changes** associated with anxiety. Studies have shown that people with long-term anxiety may experience shrinkage or reduced volume in certain brain regions, particularly the hippocampus, which plays a central role in memory formation and spatial navigation. The hippocampus is highly sensitive to stress hormones, and its deterioration is a hallmark of dementia. Anxiety can also affect the prefrontal cortex, which governs executive functions like decision-making and attention, further impairing cognitive abilities.

Anxiety often coexists with other psychiatric conditions, such as depression and mood disorders, and this combination appears to significantly amplify dementia risk. Research indicates that having multiple psychiatric disorders concurrently can increase the odds of developing dementia dramatically—up to eleven times higher when four or more disorders are present. Specifically, the co-occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders has been linked to nearly a 90% increased probability of dementia. This suggests that the combined burden of mental health issues may serve as an early warning sign or even a contributing cause of cognitive decline.

Sleep disturbances, which are common in anxiety disorders, also play a crucial role. Chronic insomnia and poor sleep quality can accelerate brain aging and increase the accumulation of amyloid plaques and white matter abnormalities—both pathological features associated with dementia. Sleep is essential for clearing toxic proteins from the brain, and disrupted sleep patterns impair this process, potentially hastening neurodegeneration.

Behavioral and lifestyle factors linked to anxiety further compound dementia risk. Anxiety can lead to social withdrawal, reduced physical activity, poor diet, and neglect of medical care, all of which are known risk factors for cognitive decline. Moreover, anxiety may impair the ability to manage other health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes, which themselves increase dementia risk.

It is also important to consider that anxiety might not only contribute causally to dementia but could also be an early symptom or marker of underlying neurodegenerative changes. The brain changes that cause dementia may initially manifest as anxiety or mood disturbances before more obvious cognitive symptoms appear. This complicates the understanding of cause and effect but highlights the importance of early mental health screening and intervention.

In summary, anxiety increases dementia risk through a complex interplay of chronic stress and inflammation, brain structural changes, coexisting psychiatric disorders, sleep disruption, and adverse lifestyle factors. These pathways collectively undermine brain resilience and accelerate cognitive decline, making anxiety a significant factor to address in dementia prevention strategies.