Controlling atrial fibrillation (AFib) can potentially reduce the risk of dementia, particularly vascular dementia, by improving heart function and reducing harmful effects on the brain. AFib is an irregular and often rapid heart rhythm that can lead to blood clots, stroke, and impaired blood flow. These cardiovascular complications are closely linked to cognitive decline and dementia, making AFib management an important factor in brain health.

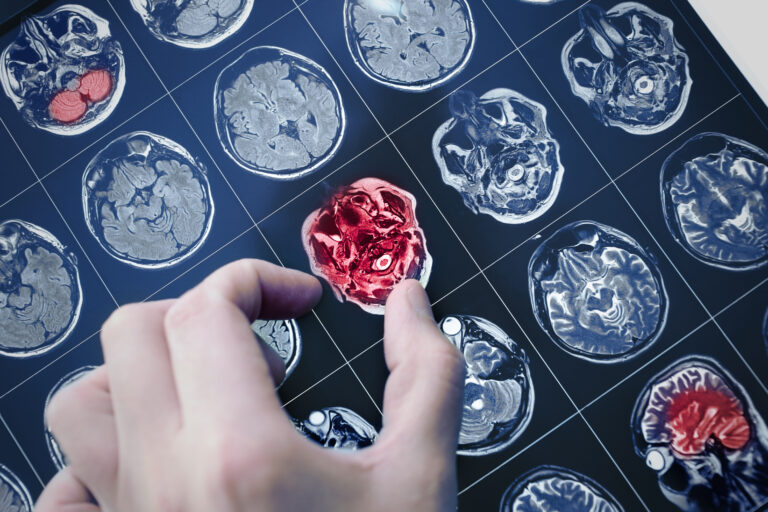

Atrial fibrillation increases dementia risk through several mechanisms. First, AFib raises the chance of stroke, including silent strokes that may go unnoticed but cause cumulative brain damage. Strokes disrupt blood flow to the brain, leading to neuronal injury and cognitive impairment. Even in the absence of stroke, AFib is associated with reduced cardiac output and irregular blood flow, which can cause chronic cerebral hypoperfusion—insufficient blood supply to the brain. This chronic hypoperfusion can damage brain tissue over time, contributing to cognitive decline.

Inflammation also plays a key role. Both AFib and dementia share inflammatory pathways that damage blood vessels and brain tissue. Inflammation can activate platelets and promote clot formation, further increasing stroke risk and vascular damage. This vascular injury can weaken the blood-brain barrier, a protective layer that regulates substances entering the brain, allowing harmful agents to trigger neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.

Managing AFib typically involves controlling the heart rhythm or rate and preventing stroke through anticoagulation therapy. Effective anticoagulation reduces the formation of blood clots, significantly lowering stroke risk and thus protecting the brain from ischemic injury. Some studies suggest that patients with well-managed AFib, especially those on appropriate anticoagulants, have a lower incidence of dementia compared to those untreated or poorly managed. This implies that controlling AFib not only prevents strokes but may also reduce the progression of cognitive decline.

Beyond anticoagulation, interventions that restore and maintain normal heart rhythm, such as catheter ablation or medications, may improve cerebral blood flow and reduce the burden of irregular heartbeats that contribute to brain hypoperfusion. Additionally, managing other cardiovascular risk factors common in AFib patients—such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart failure—can further protect cognitive function by reducing overall vascular damage.

However, the relationship between AFib control and dementia risk is complex and not fully settled. Some research has found inconsistent associations, possibly due to differences in study populations, diagnostic methods, and treatment adherence. For example, certain cohorts did not show a significant link between AFib and dementia after adjusting for other factors, suggesting that comorbidities and timing of cardiovascular events also influence dementia risk.

In summary, controlling atrial fibrillation through stroke prevention, rhythm management, and comprehensive cardiovascular care appears to reduce dementia risk by minimizing brain injury from strokes, improving cerebral blood flow, and limiting vascular inflammation. While more research is needed to clarify the extent of this protective effect and the best management strategies, current evidence supports the importance of AFib control as part of a broader approach to preserving cognitive health.