Aspirin therapy has been studied extensively for its potential to lower the risk of dementia, but the relationship is complex and not definitively established. Aspirin is primarily known for its blood-thinning properties, which help prevent blood clots and reduce the risk of stroke and heart attack. Since vascular health is closely linked to brain health, particularly in vascular dementia, aspirin’s role in preventing blood clots could theoretically reduce dementia risk by protecting the brain’s blood vessels from damage.

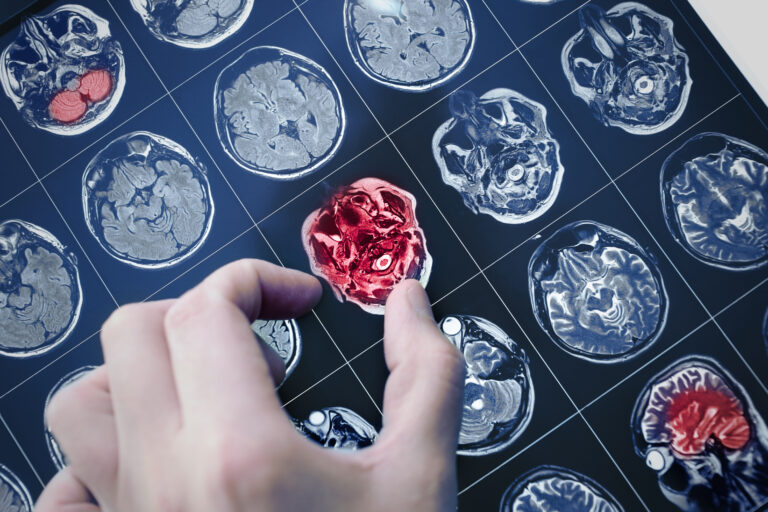

Dementia is a broad term that includes various types, with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia being the most common. Vascular dementia results from problems in blood supply to the brain, often caused by strokes or other vascular conditions. Because aspirin reduces clot formation, it has been considered a potential preventive measure against vascular dementia. However, studies show mixed results. While aspirin is effective in preventing major strokes, it does not appear to be as effective in preventing smaller, covert strokes that may silently contribute to cognitive decline. These covert strokes and other subtle vascular changes can accumulate and lead to vascular cognitive impairment, which aspirin may not fully prevent.

In terms of Alzheimer’s disease, which involves the buildup of abnormal proteins in the brain rather than primarily vascular issues, aspirin’s benefits are less clear. Research has not found a strong or consistent protective effect of aspirin against Alzheimer’s disease. This suggests that aspirin’s potential to lower dementia risk may be more relevant to vascular dementia or mixed dementia types, where vascular factors play a significant role.

Beyond its blood-thinning effects, aspirin also has anti-inflammatory properties. Chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a factor in the development of dementia, including Alzheimer’s. Some researchers have hypothesized that aspirin’s anti-inflammatory action might help reduce dementia risk by dampening harmful brain inflammation. However, clinical trials have not conclusively demonstrated that aspirin’s anti-inflammatory effects translate into meaningful protection against cognitive decline or dementia.

It is important to consider that aspirin therapy is not without risks. Long-term use can increase the chance of bleeding complications, including gastrointestinal bleeding and hemorrhagic stroke. Therefore, aspirin is generally recommended only for individuals with specific cardiovascular risk profiles, and its use solely for dementia prevention is not currently standard medical practice.

Other factors play crucial roles in dementia risk reduction, such as managing metabolic syndrome (a cluster of conditions including high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat, and abnormal cholesterol levels), maintaining good sleep quality, addressing hearing loss, and adopting a positive attitude toward aging. These lifestyle and health factors may have a more direct and modifiable impact on lowering dementia risk than aspirin alone.

In summary, while aspirin therapy has theoretical benefits for reducing dementia risk through vascular protection and anti-inflammatory effects, current evidence does not strongly support its routine use for dementia prevention. Its protective effects may be limited mainly to vascular dementia, and even then, aspirin may not prevent all types of vascular brain injury that contribute to cognitive decline. Ongoing research and large clinical trials are needed to clarify aspirin’s role and to discover more effective treatments for preventing dementia related to vascular causes.