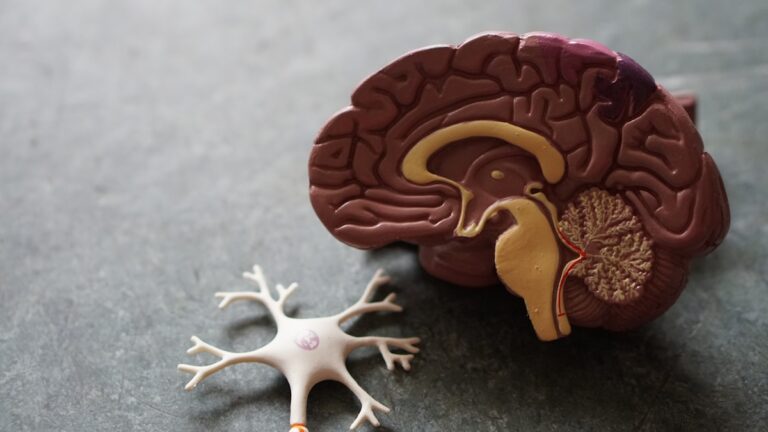

A vegetarian diet, which emphasizes plant-based foods such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, and legumes while excluding meat and sometimes other animal products, may contribute to lowering the risk of dementia but is unlikely to prevent it entirely on its own. Evidence suggests that diets rich in plant-based foods are associated with better cognitive health and a slower progression of age-related neurodegenerative diseases. However, dementia prevention is complex and typically requires a combination of lifestyle factors beyond diet alone.

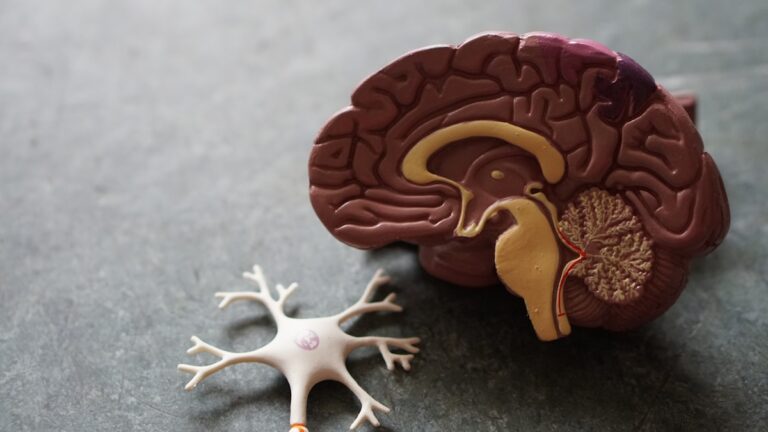

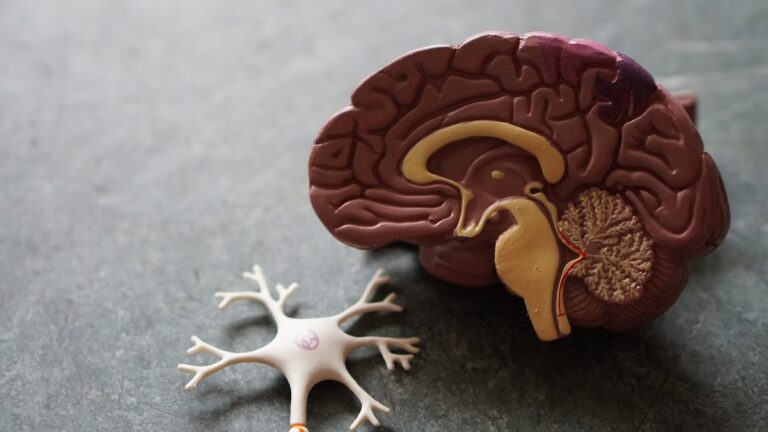

Plant-based diets tend to be high in antioxidants, vitamins (such as folate), fiber, unsaturated fats from nuts and seeds, and phytochemicals that help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress—two key contributors to brain aging. For example, leafy greens like spinach are particularly beneficial because they improve blood flow to the brain and support gut-brain communication pathways that influence cognition. These nutrients collectively may help maintain brain function by protecting neurons from damage over time.

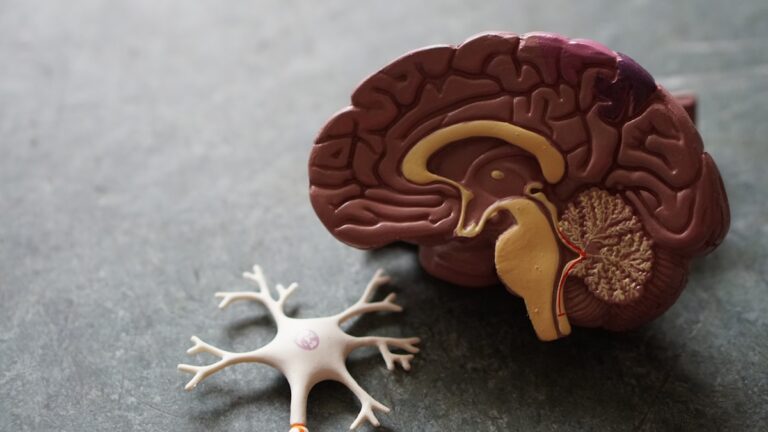

Studies have shown that adherence to dietary patterns similar to vegetarianism—such as the Mediterranean diet or other healthy eating plans emphasizing vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, whole grains, fish/seafood (in pescatarian variants), and healthy oils—correlates with reduced incidence of mild cognitive impairment or slower cognitive decline in older adults. These diets also lower cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension and diabetes that are strongly linked with dementia development.

However:

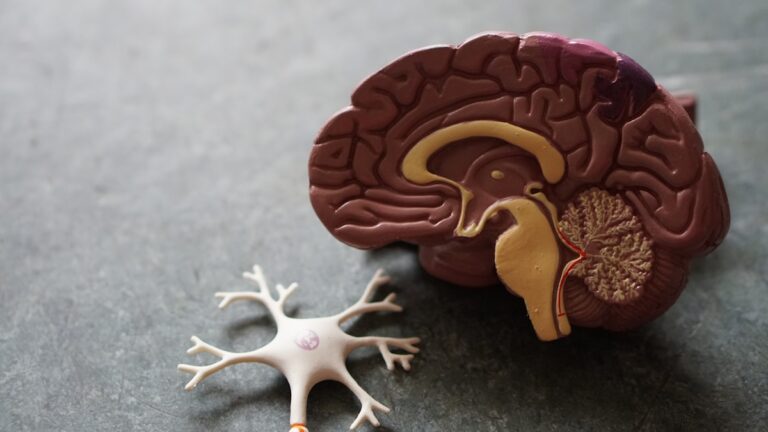

– Diet alone has not been proven sufficient for clinically meaningful reductions in dementia risk; multidomain approaches combining diet with regular physical exercise, cognitive training/stimulation activities, social engagement (which supports mental health), sleep quality management—and control of cardiovascular risks—are more effective strategies.

– Some randomized controlled trials have failed to find significant short-term benefits on brain volume or cognition from specific dietary interventions alone when tested over only a few years in at-risk populations without baseline impairment.

– Plant-based diets must be carefully planned because they can lack certain micronutrients important for brain health such as vitamin B12 (critical for nerve function), vitamin D3 (linked with neuroprotection), iron (for oxygen transport), calcium (for neuronal signaling), and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA/DHA found mainly in fish oils. Supplementation or fortified foods might be necessary.

The biological mechanisms behind how vegetarian or plant-rich diets protect against dementia likely involve multiple pathways: reducing systemic inflammation; improving vascular health; modulating metabolic processes related to insulin resistance; influencing gut microbiota composition which affects neuroinflammation; inhibiting harmful molecular targets involved in aging such as mTOR signaling; enhancing antioxidant defenses via sirtuins activation; among others.

In addition:

– Maintaining a healthy weight through balanced nutrition combined with physical activity reduces chronic conditions like hypertension or type 2 diabetes that increase dementia risk.

– Social factors often intertwined with lifestyle choices also play an important role: populations known for longevity (“Blue Zones”) combine plant-heavy diets with strong social ties which together promote overall well-being including cognitive resilience.

In summary terms without concluding: A vegetarian diet rich in diverse plants can form an important part of a holistic approach aimed at preserving brain health into old age by mitigating some modifiable risks linked to vascular disease and inflammation. Yet preventing dementia outright requires addressing multiple interconnected lifestyle domains alongside careful nutritional planning tailored individually for nutrient adequacy.