Alzheimer’s disease devastates the brain by progressively eroding memory, cognition, and daily function, with synapse loss—a breakdown in neural connections—emerging as a key early driver of these symptoms. While amyloid plaques and tau tangles have long dominated research, recent studies reveal specific proteins that actively block or prune these vital synapses, accelerating dementia’s grip on brain health.

Understanding these mechanisms offers hope for targeted interventions that could preserve cognitive function longer.[1][2][3] In this article, readers will explore how proteins like Mdm2, Centaurin-α1, and complement inhibitors disrupt synaptic integrity in Alzheimer’s, drawing from cutting-edge research on rodent models and human brain tissue. You’ll gain insights into protective proteins that counter this damage, potential therapeutic targets, and practical steps to support brain health amid rising dementia risks. This knowledge empowers those affected by or caring for loved ones with Alzheimer’s to stay informed on emerging science.

Table of Contents

- How Do Proteins Trigger Synapse Loss in Alzheimer’s?

- Which Proteins Protect Synapses from Elimination?

- What Happens When We Block Harmful Proteins?

- Therapeutic Targets and Emerging Strategies

- Links to Broader Alzheimer’s Pathology

- How to Apply This

- Expert Tips

- Conclusion

- Frequently Asked Questions

How Do Proteins Trigger Synapse Loss in Alzheimer’s?

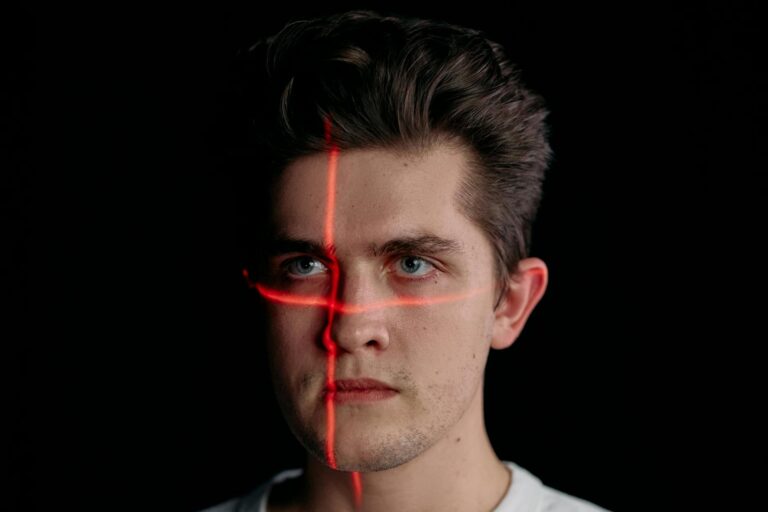

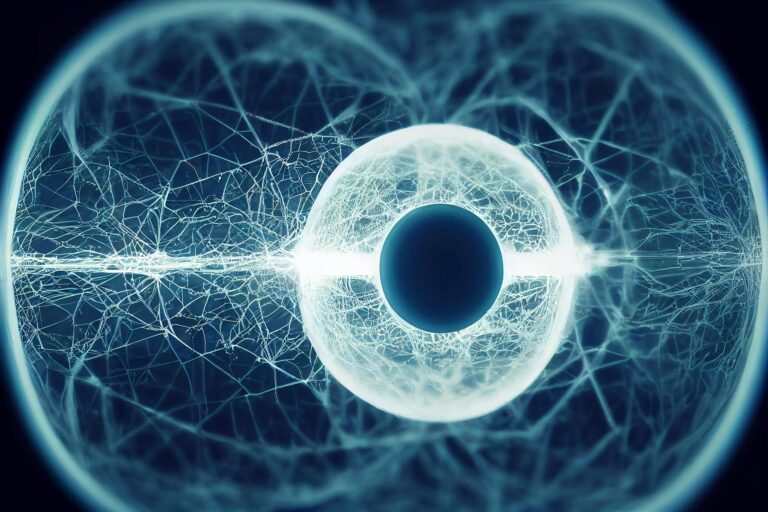

Synapse loss, particularly in the hippocampus—the brain’s memory hub—correlates strongly with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s, often preceding widespread plaque buildup. Proteins like Mdm2 become hyperactive in the presence of amyloid-beta (Aβ), the peptide forming hallmark plaques, leading to excessive pruning of dendritic spines and excitatory synapses. This abnormal trimming mimics normal brain development but spirals out of control, erasing connections essential for learning and memory.[1] Research from the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus demonstrates that inhibiting Mdm2 with drugs like nutlin fully blocks Aβ-induced spine loss in rodent neurons, highlighting its direct role in synaptic destruction. Similarly, Centaurin-α1, elevated in Alzheimer’s brains, drives neuroinflammation, plaque accumulation, and hippocampal synapse damage, as shown in mouse models where its removal preserved neural connections and improved spatial learning.[3] Meanwhile, the brain’s complement system, part of immune signaling, tags synapses for elimination by microglia—immune cells that “eat” them. In Alzheimer’s, this process runs amok, but protective proteins like SRPX2 act as “don’t eat me” signals to safeguard synapses during vulnerable periods.[2]

- **Mdm2’s pruning effect**: Aβ activates Mdm2, causing over-pruning of dendritic spines in the hippocampus.[1]

- **Centaurin-α1’s broad impact**: Its absence reduces plaques by 40%, curbs inflammation, and protects synapses.[3]

- **Complement overdrive**: Immune tagging eliminates excess synapses, unchecked in disease.[2]

Which Proteins Protect Synapses from Elimination?

The brain employs built-in defenders against synaptic pruning, with proteins like SRPX2 emerging as critical inhibitors of the complement system. This immune pathway normally clears weak synapses during development, but in Alzheimer’s, its hyperactivity contributes to widespread loss. SRPX2 restricts complement activation, preserving specific synapse populations in mouse models, suggesting it prevents runaway elimination in dementia.[2] Studies indicate SRPX2’s activity is time- and region-specific, activating precisely when synapses need protection. Loss of such inhibitors may explain accelerated synapse decline in Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, and related disorders, positioning them as therapeutic boosters.[2]

- **SRPX2 as a shield**: Inhibits complement-mediated eating of synapses, vital during brain development and disease.[2]

- **Timing matters**: Protects synapses in targeted brain areas, averting excess loss.[2]

What Happens When We Block Harmful Proteins?

Inhibiting destructive proteins yields striking results in preclinical models. Blocking Mdm2 with nutlin completely halted Aβ-driven synapse loss, restoring balance to dendritic spines without toxicity.[1] Removing Centaurin-α1 in Alzheimer’s mice normalized gene expression, slashed hippocampal plaques by 40%, quelled inflammation, and rescued spatial memory—effects linked to preserved neural connections.[3] These findings underscore multifunctional roles: Centaurin-α1 disrupts signaling for actin dynamics, synaptogenesis, and amyloid processing, while its knockout recalibrates brain pathways. Such interventions suggest blocking these proteins could slow progression if translated to humans.[1][3]

- **Mdm2 inhibition success**: Nutlin prevents pruning, a potential repurposed cancer drug for Alzheimer’s.[1]

- **Centaurin-α1 knockout benefits**: Reduces damage across inflammation, plaques, and cognition.[3]

Therapeutic Targets and Emerging Strategies

Targeting synapse-blocking proteins opens new avenues beyond amyloid clearance. Mdm2 inhibitors like nutlin, already in cancer trials, show promise for halting early synaptic loss, while Centaurin-α1 reduction normalizes broad disease processes, from metabolism to neural wiring.[1][3] Complement modulators, inspired by SRPX2, could enhance “don’t eat me” signals to protect synapses.[2] Gene expression analyses reveal these proteins orchestrate cascading damage, making them high-value targets. Challenges remain in adult-onset delivery, but rodent successes fuel human trials, potentially combining with anti-amyloid therapies for synergy.[3]

Links to Broader Alzheimer’s Pathology

Synaptic sabotage by these proteins intertwines with classic hallmarks like Aβ plaques and tau tangles. Aβ directly activates Mdm2 and complement, while Centaurin-α1 associates with plaques and fuels tau-related inflammation. Synapse loss precedes tangles, amplifying neurotoxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction in remaining connections.[1][3][7] Beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) elevation promotes Aβ aggregation, indirectly worsening synaptic block, while impaired protein synthesis—via phosphorylated eIF2—starves neurons of repair machinery. Restoring synthesis with ISRIB improves memory in models, hinting at holistic strategies addressing protein dysregulation.[4][5]

How to Apply This

- Discuss genetic risks with a doctor, focusing on Alzheimer’s models highlighting modifiable protein pathways.

- Prioritize brain-healthy habits like Mediterranean diet and exercise to reduce inflammation and support synaptic resilience.

- Stay informed on clinical trials for Mdm2 or Centaurin-α1 inhibitors via Alzheimer’s Association resources.

- Monitor cognition early with validated tests, seeking interventions at first signs of memory lapse.

Expert Tips

- Tip 1: Boost omega-3 intake to mimic anti-inflammatory effects seen in protein-knockout models.[3]

- Tip 2: Engage in regular aerobic exercise, which preserves hippocampal synapses akin to protective proteins.[1]

- Tip 3: Prioritize sleep hygiene, as it regulates complement activity and clears Aβ debris.[2]

- Tip 4: Consider cognitive training apps targeting spatial memory, bolstered by research on preserved connections.[3]

Conclusion

Proteins like Mdm2 and Centaurin-α1 actively dismantle synapses in Alzheimer’s, but blocking them in models halts damage, protects memory circuits, and normalizes brain function—signaling a shift toward synapse-centric therapies. Protective agents like SRPX2 reveal the brain’s defenses, offering blueprints for drugs that amplify natural safeguards against dementia’s synaptic assault.[1][2][3] For those navigating dementia, this science underscores proactive brain health: while we await trials, lifestyle measures can fortify synapses today. Emerging insights promise to transform Alzheimer’s from inevitable decline to manageable progression, preserving quality of life longer.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main protein blocking synapses in Alzheimer’s?

Mdm2, activated by amyloid-beta, excessively prunes dendritic spines and synapses, as shown in University of Colorado studies using nutlin inhibition.[1]

Can removing Centaurin-α1 reverse Alzheimer’s symptoms?

In mouse models, its elimination reduced plaques by 40%, curbed inflammation, preserved hippocampal connections, and improved spatial learning, but human trials are needed.[3]

How does SRPX2 protect the brain?

SRPX2 acts as a “don’t eat me” signal, inhibiting the complement system’s synapse elimination, crucial for preventing excess loss in Alzheimer’s and development.[2]

Are there drugs already targeting these proteins?

Nutlin, an experimental cancer drug, blocks Mdm2 and stops synapse loss in models; ISRIB restores protein production to aid memory, with ongoing research.[1][5]