A poor diet appears to increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and may speed up the changes in the brain that lead to memory loss, especially when that diet is high in refined carbohydrates, added sugars, unhealthy fats, and ultra processed foods[1][8]. Researchers are also finding that healthier eating patterns, such as versions of the Mediterranean or MIND diets, are linked with a lower risk of cognitive decline and dementia[5][8].

What scientists mean by “poor diet”

When researchers talk about a “poor” diet in brain health studies, they usually mean patterns like the Western diet, which is rich in fast food, sugary drinks, processed meats, refined grains, and sweets, and low in vegetables, fruit, whole grains, and legumes[8]. A recent review in Public Health reports that strong adherence to a Western diet is associated with higher risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease, while healthier patterns show the opposite trend[8].

In contrast, diets built around whole plant foods, nuts, olive oil, fish, and modest dairy, such as the Mediterranean or MIND style diets, are repeatedly associated with slower mental aging and lower dementia risk[5][4][8]. The cMIND diet, a culturally adapted version of MIND tested in older adults, was linked to a significantly lower risk of developing cognitive impairment in people who followed it closely compared with those who did not[5].

How high sugar and refined carbs may harm the brain

Not all carbohydrates affect the brain in the same way. A large study of over 200,000 adults in the UK found that diets high in glycemic index, meaning they cause sharp blood sugar spikes, were linked to a higher risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, while low to moderate glycemic index diets were associated with lower risk[1]. According to that research, people eating mostly low glycemic index foods such as fruit, legumes, and whole grains had about a 16 percent lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease, whereas those consuming higher glycemic index diets had roughly a 14 percent higher risk[1].

These findings fit with what scientists know about blood sugar and the brain. Frequent spikes in blood glucose can lead over time to insulin resistance, inflammation, and damage to blood vessels that supply the brain. All of these problems are also seen in Alzheimer’s disease. Although the study cited above cannot prove cause and effect, it supports the idea that a diet centered on slowly digested carbohydrates is better for long term brain health than one filled with white bread, sugary snacks, and sweetened drinks[1].

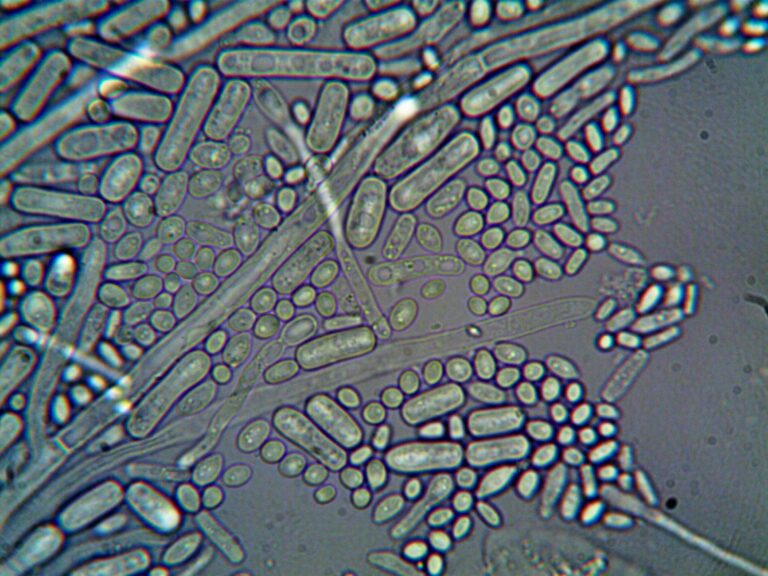

Animal research gives additional clues. In an experiment highlighted by PsyPost, older rats fed refined, low fiber diets for just three days already showed memory problems and changes in key brain regions linked to learning and emotion[2]. Their brain mitochondria, the structures that produce energy, became less efficient, especially in microglia, the brain’s immune cells[2]. Levels of butyrate, a helpful substance produced when gut bacteria digest fiber, dropped sharply, and lower butyrate was tied to worse memory performance in the aged rats[2]. While animal results do not automatically apply to people, this study suggests that removing fiber and relying on refined foods can rapidly disturb brain energy use and memory in the aging brain[2].

Fats, cholesterol, and processed foods

The relationship between dietary fat and dementia is complex. Some highly processed meats and fast foods provide large amounts of saturated and trans fats, salt, and additives, and are commonly included in Western diet patterns that predict higher dementia and Alzheimer’s risk[8]. These foods are associated with heart disease and type 2 diabetes, which are themselves risk factors for cognitive decline.

At the same time, not all high fat foods appear harmful. Several long term observational studies from Nordic and UK populations have found that eating certain full fat dairy products such as cheese and cream was associated with a modestly lower risk of dementia, particularly in people without strong genetic risk for Alzheimer’s[3][4][6][7]. For example, a Swedish study of 27,670 adults followed for 25 years found that those who consumed more than 50 grams of full fat cheese per day had about a 13 to 17 percent lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease if they did not carry the APOE ε4 risk gene variant[3][4][7]. A related analysis reported that higher intake of high fat cheese was linked to lower Alzheimer’s risk only in APOE ε4 noncarriers[7], and that more than 20 grams of high fat cream per day correlated with a 16 to 24 percent lower dementia risk in some groups[4][6].

Researchers caution, however, that these dairy results show statistical associations, not proof that cheese or cream directly protect the brain[3][4][6]. Food intake was self reported, which can be inaccurate, and there may be “substitution” effects, where people who eat more cheese or cream may be eating less processed meat or sugary foods[4]. When the Swedish team looked only at participants whose diets stayed stable over five years, they found no clear association between full fat dairy and dementia risk, which supports this idea[4].

The key message from these findings is that overall dietary patterns matter more than any one food. As ScienceAlert’s coverage of the Swedish study notes, Mediterranean style diets that combine vegetables, whole grains, fruit, fish, and moderate amounts of cheese are consistently associated with lower risks of both dementia and heart disease[4]. That suggests that cheese eaten as part of a balanced, unprocessed diet is very different from cheese in a diet dominated by fast food and processed meat.

Diet, blood vessels, and Alzheimer’s disease

One reason poor diet can accelerate Alzheimer’s changes is its impact on blood vessels. Vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease often overlap in older adults, and many brains show both Alzheimer’s plaques and damage to small blood vessels. In the Neurology study summarized by the American Academy of Neurology, people who ate larger amounts of high fat cheese had a 29 percent lower risk of vascular dementia after statistical adjustments, even though the study could not show direct causation[6]. This ties diet quality to the health of the brain’s circulation.

Western diet patterns have been linked in multiple studies to high blood pressure, high cholesterol, obesity, and diabetes, all of which damage blood vessels over time[8]. When blood vessels in the brain are injured, brain cells receive less oxygen and nutrients. This can worsen or speed up the cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease. By contrast, diets rich in plant foods, fish, and unsalted nuts appear to support healthier arteries, which may help the brain age more slowly.

How healthier diets may slow brain aging

The protective diets seen in dementia research, such as Mediterranean, MIND, and cMIND, have several features in common. They emphasize vegetables, especially leafy greens, berries and other fruits, whole grains, beans and lentils, nuts and seeds, olive or canola oil, and regular fish, while limiting red and processed meats, pastries, sweets, and fried foods[4][5][8]. In older Chinese adults, for instance, higher adherence to the cMIND diet pattern was linked with a significantly lower risk of developing cognitive impairment compare